Portraits of death: Sam Nhlengethwa

BIKO’S GHOST: THE ICONOGRAPHY OF BLACK CONSCIOUSNESS by Shannen L Hill (University of Minnesota Press)

The canon of books on Steve Biko, South Africa’s brutally assassinated Black Consciousness Movement leader, continues to grow 40 years after his death.

Shannen L Hill’s Biko’s Ghost: The Iconography of Black Consciousness is perhaps most distinctive in that it forces us to view Biko as something other than a eulogised and romanticised figure but rather one who, even four decades after he was beaten to death by security police officers, continues to shape the visual and verbal discourse about the aesthetics and meaning of Black Consciousness (BC).

Hill writes that, for the South African Students’ Organisation (Saso), which Biko cofounded, cultural work was an immediately important vehicle to propel BC ideals.

Quoting from Michael MacDonald’s Why Race Matters in South Africa, she writes of artist and poet Lefifi Tladi’s initial perceptions of the Saso cultural committee (which was soliciting and fielding proposals from artists) as “no vertical invaders” but as people whose ethos was to listen, learn, share and promote.

Artist David Koloane also appears early on in the book, as the man working with the committee to establish a gallery, which had to be put on ice when Saso was banned in 1977. Hill writes of the emergence of the solidly clenched fist as a marker of distinction from the ANC’s straight-thumbed version.

[David Koloane, The Journey, no. 13 (crouched down, engaging the viewer), 1998. Acrylic and oil pastel on paper, 29 x 42 cm framed. Courtesy of David Koloane]

She describes an emerging figuration aesthetic among the artists of the time that acknowledged the quagmire of the day but sought to express a disposition other than self-pity.

Hill creates the sense of a nexus developing, with clusters of like-minded artists emerging in Ga-Rankuwa and Mamelodi West, the latter forming around the nurturing couple that was Geoff and Maokaneng Mphakathi.

Geoff, a doyen of the black arts and African history, shared his home, books (many of which were banned), music and literature with artists such as Fikile Magadlela, Dikobe Ben Martins, Cyril Khumalo and Motlhabane Mashiangwako.

Although Hill intended to look at the BC movement in its entirety through the lens of “art history, political science, media studies and post/anticolonial theory”, the fact that Biko’s murder was a decisive moment in the trajectory of the Black Consciousness philosophy means this book can be regarded as “a Biko book”.

In the second chapter, she writes of Biko’s “global stature as evident but modest before his death”, but notes that this changed rather quickly after he died in police custody, with images of him being beamed around the world.

She goes into detail about the different, emergent portraitures of the man, as well as what she calls a distinct divide between his words and his likeness. From a survey of the press coverage that emerged about his death, Hill identifies three distinct portraitures that have influenced his legacy ever since.

There is the “everyman” in a work shirt who implores us to “stand tall”. Then there is the fallen statesman and “much-mourned intellectual”. The third is a photo of Biko’s corpse taken at his autopsy and an image that appeared at his funeral — a closely cropped headshot of a slightly tilted Biko in a suit and tie. The photo was used by Dikobe Ben Martins in a mass-produced funeral poster.

She writes that, because of this context, this otherwise statesmanly portrait of Biko became a “visual condemnation of a government that ruled by violence”, a kind of death mask that, to paraphrase, generates a history of its own.

It is clear from Hill’s book that Black Consciousness remains a hotly contested ideological terrain and one that is frequently co-opted for political or social currency. Her own personal interpretation of BC — as “not about racial awareness” but “about liberating oneself from oppression” — shapes many of the editorial choices in the book.

Paul Stopforth, a fine arts lecturer at the University of the Witwatersrand at the time, opened a show at the Market Theatre a week after Biko’s death. Figures, an installation of sculptures about deaths in detention, became inevitably linked to Biko in the mainstream press.

Whereas in the previous chapters Hill paints in broad brushstrokes, she gives considerable attention to Stopforth’s work and its timing, stating that he was essentially fulfilling the BC mandate by creating works that sought to conscientise white audiences.

As a way of looking at contrasting approaches, influenced by their positions as insider-outsider, Hill contrasts Stopforth with artist Ezrom Legae, who was shaken out of a rut by Biko’s death to produce a series of abstract works. The comparisons seem incidental, except maybe to make the point that the commemoration of Biko’s life did not always prioritise a literal approach in terms of figuration, a theme she explores throughout the book.

“BC artists of the 1970s endorsed technical and aesthetic experimentation as inherently black; critics have called many of them ‘African surrealists’, a label far too confining to hold much meaning,” she writes in a chapter called “Silencing the Censors”.

In a chapter about Biko’s portrayal during the dawn of democracy in South Africa, she writes that the dominant narrative required — “and still does to a large extent” — that Biko should be portrayed as a benevolent, Christ-like figure.

She quotes librettist Richard Fawkes as saying that Biko was in the Gandhi tradition, because he wanted “not to replace white rule with black rule”. Rian Malan, in My Traitor’s Heart, says: “I could scarcely believe in my secret racist heart that a black could be so wise and perceptive and the awe I felt for him had almost religious overtones.”

The problem is not so much that Hill goes out of her way to include these comments, it is that she barely moves an inch in categorising such comments as problematic, saving her harder-hitting critique for the ANC instead.

She argues that, instead of killing the movement, the repression of the 1970s merely splintered it into different camps, with BC-inflected icono-graphy thriving in movements that “either publicly claimed the mantle of Black Consciousness in the 1980s or derided it as a thing of the past, irrelevant to their own methods or mission”.

Hill argues that the ANC had no use for culture before the BC movement identified it as a medium of struggle. She maintains that part of why culture was important from the outset for BC-affiliated bodies such as Saso and the Black People’s Convention was that these groups were operating above the radar and without armaments.

The Medu Arts Ensemble, writes Hill, was formed by “Black Consciousness adherents who sought and gained ANC affiliation in 1980”. It is this fact, she says, that has caused scholars to “credit this party and its platform with the rise of resistance aesthetics in South Africa”.

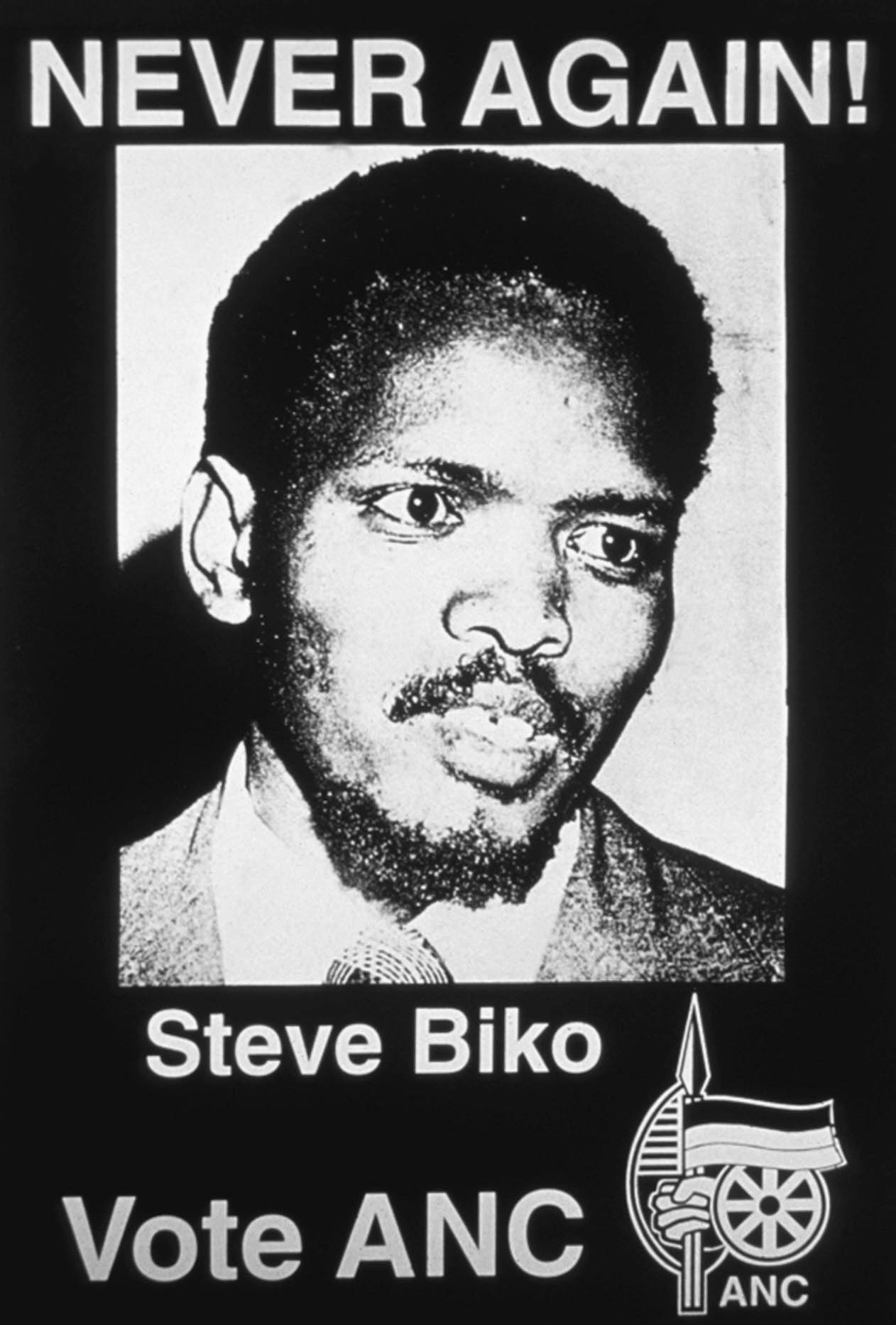

Of all the images referenced in the book, the most jarring is perhaps an innocuous one from a South African perspective, culled from a 1994 election poster.

An image of Biko used as a funeral publicity poster is repurposed by the ANC as an election poster: “NEVER AGAIN!” it screams at the top of the image. “Steve Biko” appears below, with “Vote ANC” and an ANC logo for punctuation.

[Never Again! ANC election poster, 1994. South African History Archive, University of the Witwatersrand.]

Hill argues that, given the image’s popular use at Biko’s funeral, it forever “registers as a portrait of death”. In using his “death mask”, she says, the Never Again! poster becomes, in effect, “a portrait of torture”.

Homing in on post-apartheid South Africa, Hill posits Biko as a nightmare for easy or, at least, self-serving monumentalisation.

One of the book’s later chapters, “Museum, Monument and Marking”, touches on the occasion of the unveiling of the Biko Monument in East London, with Nelson Mandela working overtime to placate irate Azanian People’s Organisation and Pan Africanist Congress members who felt a legitimate claim to Biko.

The statue, at the city hall, was privately commissioned and funded by the former editor of the Daily Dispatch, Donald Woods.

Woods approached his neighbour, Naomi Jacobson, to create the statue. Jacobson, writes Hill, had been known for “her portraits of black leaders, most of which were busts rather than larger-than-life representations”. Jacobson apparently based her portrayal of Biko on Woods’s memory of the man, which she gleaned from evenings of visiting him “over wine”, discussing “such particulars as Biko’s watch, clothing and how he would have typically stood”.

Hill says Jacobson aimed to create an image of self-confidence — but, Jacobson cautioned, one that was “not aggressive” in appearance and would not make anyone “upset”.

Hill regards the resultant midget-like, tall-plinthed monument as “stiff” and “ill-proportioned”, and Woods’s actions as premature, as he could have acted in partnership with the Biko Foundation, which launched in the same week as the East London statue was unveiled.

Given the wide interpretative possibilities of Black Consciousness as a philosophy, everyone who approaches the topic does so bearing their particular world view. Hill in Biko’s Ghost is no exception, going to lengths, for instance, to highlight Nobel laureate Nadine Gordimer’s role as a defender of BC to an “almost all-white audience” at a 1979 State of the Art conference at the University of Cape Town.

But as a torch that can be passed on for further studies, Biko’s Ghost is an admirable work of study and cross-referencing. In her closing remarks, Hill seems to suggest that her work, nine years in the making, can be improved by contributions from others working in a similar field of study. Despite its episodic, grating incents of liberalism, equalling its breadth will take some doing.