'As electricity tariffs rise

Eskom is facing a fundamental crisis that is only being exacerbated by allegations of corruption and the leadership vacuum at the state power company.

Almost half of the latest tariff increase Eskom has asked for is aimed at making up for the power utility’s dropping sales.

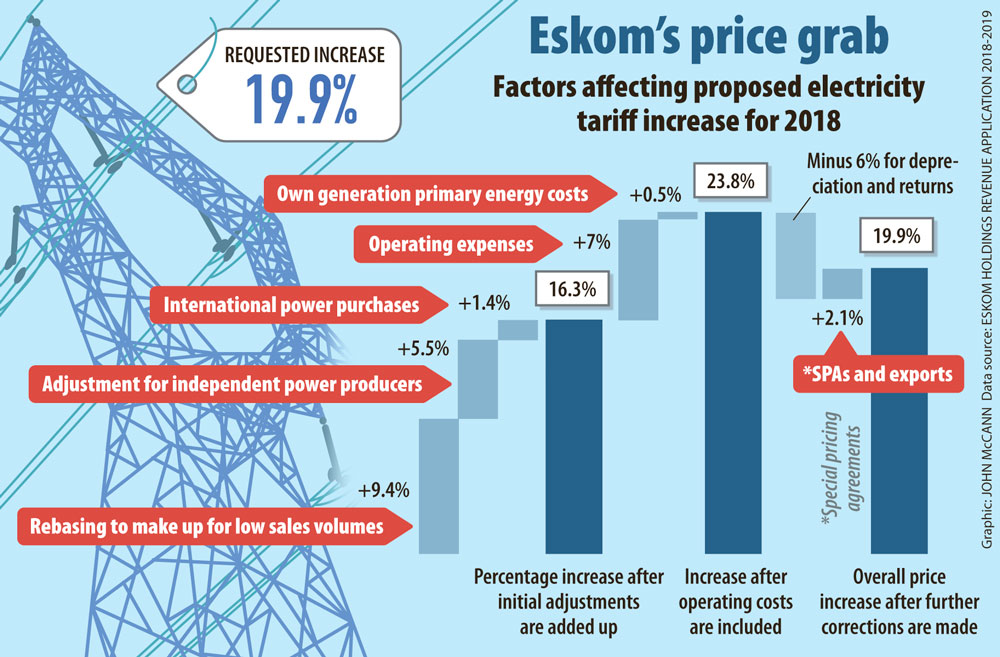

In its latest tariff application to the National Energy Regulator of South Africa (Nersa), the power utility requested an increase of 19.9% for the 2018-2019 financial year, which will take its standard tariff from about 89c per kilowatt-hour to almost R1.07/kWh.

About 9.4% of this increase is accounted for by what Eskom terms “sales volume rebasing” — or the declines in electricity sales.

This rebasement, as well as a price adjustment of 5.5% because of further increases to cover independent power producer (IPP) costs, comes before some of Eskom’s other major expenses, such as primary energycosts — mainly coal — are even contemplated.

It is also seeking a 27% tariff increase for municipalities.

As tariffs rise, the problem of plummeting sales is only likely to worsen.

Critics have complained that, although a range of factors may have contributed to customers cutting their electricity consumption, this is aggravated by Eskom’s own inefficiencies, which have forced up prices.

Not least of these has been the rapid increases in tariffs to pay for a capital expansion programme that has been dogged by cost overruns and delays.

Eskom’s need to cover for falling sales arguably hints at what has become known globally as the utility death spiral — when customers switch to alternative, off-grid electricity sources that are increasingly competitive, forcing utilities to ask regulators to increase tariffs. In turn, more customers look for cheaper alternatives and utilities must rely on an ever-declining revenue pool.

In its feedback on Eskom’s application to hike tariffs, the treasury also alluded to this looming problem.

Its research found that 26% of residential electricity sales could be off-grid by 2030. This was based on a moderate tariff increase path of 10% a year for the coming five years.

From an analysis of listed companies, the treasury estimated the equivalent of up to 34% of mining, 8% of industrial and 1% of commercial electricity generation sales currently supplied by Eskom could potentially go off-grid by 2040.

These effects would be driven by the mitigation strategies put in place by households — particularly high-income households — and firms in response to rising electricity prices, it noted.

But Eskom’s requested increase has also coincided with a series of corruption scandals and four chief executives since the start of 2017.

Most recently, Eskom all but admitted to paying consultancies McKinsey and Trillian — the latter was previously linked to controversial Gupta family associate Salim Essa — about R1.6‑billion in unlawful payments.

The parastatal has also been plagued by allegations of corrupt coal procurement processes — including preferential treatment for Gupta-linked companies. In its financial results, almost R3‑billion was revealed to have been spent in contravention of the Public Finance Management Act.

Eskom said that the sales volume rebasement is in line with the methodology that Nersa uses to make multiyear price determinations (MYPD) on the tariffs it grants Eskom.

In terms of the MYPD methodology, allowable revenue is recovered from the assumed sales volume, Eskom said.

Owing to a significant decline in sales volumes from those that were assumed in Nersa’s previous tariff decision — or the MYPD3 — the rebasing is included, it said.

It also stressed that the allowable revenue that Eskom is requesting for the 2018-2019 year is R219.5‑billion. This amounted to a 7% increase from the previous Nersa decision for the 2017-2018 year of R205.2‑billion.

Eskom said that the lower sales volumes were caused by the “possible impact of price elasticity of demand” and “reliability of Eskom supply”.

Other factors it cited as contributing to declining sales included lower-than-anticipated economic growth and a “reluctance by global companies to invest in South Africa due to a lack in competitiveness and the uncertain situation in South Africa from a political and sustainable financial perspective”.

The treasury and the South African Local Government Association (Salga) questioned this sales rebasement and asked for clarity on the IPP cost adjustment.

In its comments, included in Eskom’s application, the association said: “Salga is concerned about the increase in costs despite the continuing decline in sales volumes. Clarity is sought on why costs do not drop when sales volumes decrease.”

Salga also raised concerns with the methodology that “allows Eskom to increase the tariff to cover for lower sales to maintain the rand value of the income”.

Although the current law allowed for this kind of price adjustment, it was problematic, said Chris Yelland, managing director of EE Publishers.

To address this, he said, the government needed to implement its 1998 white paper on electricity policy — including the introduction of an inde