ANC chief whip Stone Sizani.

Some remote Australian communities have access to drinking water for only nine hours a day for part of the year, but these households can still use up to ten times the average of urban households.

Many communities in the Torres Strait Islands have their mains water supply limited to nine hours a day during the week, and 16 hours a day at weekends, during the six-month dry season from May to October. Some remote Aboriginal communities in mainland Australia have similar restrictions.

READ MORE: Water in northern Australia: a history of Aboriginal exclusion

The vast majority of these residents do not pay directly for water, as they live in public housing. A three-year research project has been using smart meters to monitor water use as well as promoting community discussion. We found the water is largely used for things that might be viewed as luxuries in an urban setting but which play an important role in community life, such as dampening roofs for cooling and washing fishing gear.

The challenge, therefore, is finding ways to manage this unsustainable water use, apart from physically turning off the water. By understanding the challenges of life in remote Australia and working closely with locals, we identified some reasonable and realistic ways to reduce water use.

Revealing the reasons for high water use

Water restrictions, which have been in place on and off since the early 2000s, exist for a simple reason: there is not enough water to meet demand, especially during the dry season.

Providing water to remote and isolated communities is expensive, whether it comes from a desalination plant (which turns seawater into drinking water) or from a groundwater bore. Typically a diesel generator is used to generate power for water extraction, treatment, pumping and sewage management.

[Leaking taps contribute to high water use in some remote communities. (Cara Beal/The Conversation)]

[Leaking taps contribute to high water use in some remote communities. (Cara Beal/The Conversation)]

For the past three years I have led a team of Griffith University researchers investigating how water was being used, and how it could be reduced. We installed smart meters in three remote communities, across the Torres Strait Islands, Cape York and the Northern Territory.

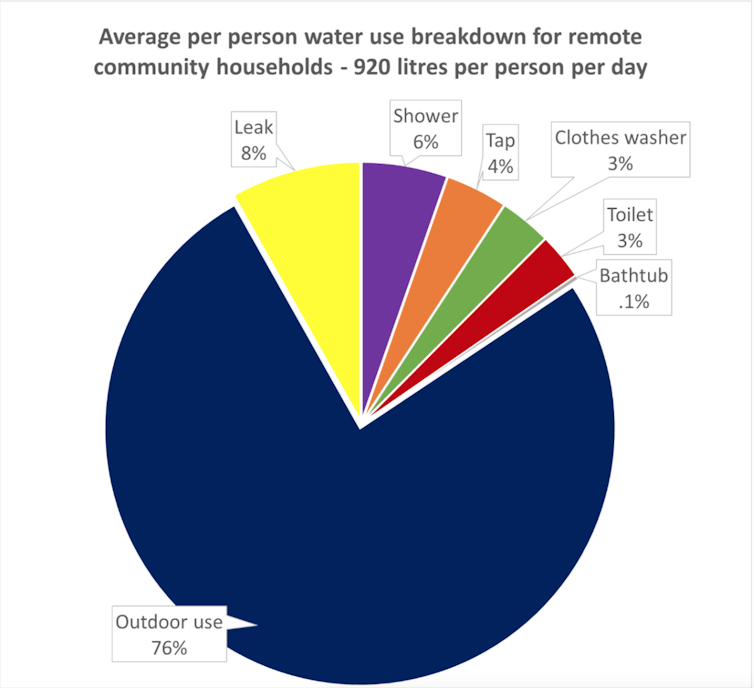

The data revealed an average daily use of 900 litres per person, rising to more than 4,000L per person per day in some cases. (The average southeast Queensland household daily use is around 180L per person.) Once the energy costs of pumping and treating this water via diesel-fuelled generators are included, it’s clear this is unsustainable.

We then broke down household water use into categories such as showering and outdoor, and discussed water use habits with each participating household. This gave unprecedented insights into how, where and why water is being used in remote community households.

Beating the dust and heat

Outdoor water use makes up, on average, at least 75% of total household water demand. This can get even higher in the dry season. Leaking taps are also a major contributor.

[Average residential water use per person in three remote communities from Far North Queensland and the Northern Territory. Cara Beal/The Conversation)]

[Average residential water use per person in three remote communities from Far North Queensland and the Northern Territory. Cara Beal/The Conversation)]

We spoke to participants in Cape York and the Torres Strait about their water use during the middle of the dry season. We found five key drivers for this high outdoor water use (aside from leaks):

- dust control (and flea control) from non-surfaced roads and yards

- cooling down (watering the house roof and bare earth or concrete driveways to create an evaporative effect)

- washing down boats and fishing or hunting equipment

- physical amenity (gardening or greening)

- social amenity (having a continuous source of tap water was an important resource during social gatherings, including sorry camps, tombstone openings, cultural events and extended family gatherings).

Reducing drivers of high water use

In urban areas, outdoor household water use is often described as “discretionary”. This implies that the water is associated with “wants” (like car washing, irrigation or filling pools) more than “needs” (drinking, cooking or personal hygiene).

But in the case of these remote communities, our research suggests that outdoor water use is often linked directly to health and well-being. In areas where temperatures during winter regularly climb above 30℃, dust suppression, cooling and flea control are not trivial desires.

[Water is used for controlling dust from unsealed roads and bare earth in remote communities. (Cara Beal/M&G)]

[Water is used for controlling dust from unsealed roads and bare earth in remote communities. (Cara Beal/M&G)]

This means that simply adopting the typical urban water management approach is unlikely to reduce demand. Poor sanitation in many Indigenous communities further complicates the situation.

READ MORE: It’s a fallacy that all Australians have access to clean water, sanitation and hygiene

The challenge is to reduce water demand, to allow restrictions to be eased in the future, while maintaining a sustainable level of water use in these communities.

Community-involved solutions

We asked our participants from two communities in western Cape York and the Torres Strait Islands how they would reduce high outdoor water use.

Overwhelmingly, they observed a need for more education and awareness of why water conservation is important. Before piped water systems, people were deeply connected to their water sources and could self-manage their supplies.

Nowadays many communities have only one or two good-quality water sources, and the Western-style built infrastructure acts as a barrier to this previous personal connection to water. The economic value of water is also poorly understood in many remote communities.

Similarly, service providers (and others) need to develop a greater understanding of the cultural, social and spiritual value of water from an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island person’s perspective.

READ MORE: The role of water in Australia’s uncertain future

Our team, together with the participants and local service providers, trialled a water efficiency pilot program. This involved both residents and local councils learning about the importance of conserving water and offering suggestions on ways to do this. Talking with the residents, it become clear that high outdoor water use was not purely driven by the fact that water is free for them.

Many of the activities were centred on health (cooling and dust suppression) and food provision (fishing and hunting). Nevertheless, ways of reducing water use were identified. These included watering after dark, reporting leaks, using tap timers and washing hunting and fishing equipment on grass.

The pilot programs have shown promising results, although their funding will shortly end. The challenge will be to change behaviour over time. If this can be done, it will go a long way to reducing the need to limit some communities to nine hours of treated water a day.

Cara Beal, Senior research fellow, Griffith University

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.