The artist demystified: El Anatsui's latest exhibition includes archival material from his studio.

Over the years I have often found myself embroiled in passionate debates both at home and abroad about what constitutes contemporary art.

Although the conversation is necessary and important, it sometimes becomes a battle of frustrations regarding the international art market and its dogmatic collecting guides about “traditional African art”, especially when talking to those who are not from the continent.

But on either side of the debate about the polarising of contemporary and traditional African art, there is one artist whose illustrious work is the confluence of both: internationally acclaimed Ghanaian-born and Nigerian-based artist El Anatsui.

Anatsui enthralled audiences at the 2007 Venice Biennale with his large-scale, cascading sculptural installations, reminiscent of kente cloth, assembled from thousands of recycled aluminium bottle-tops.

Transgressing sculptural practice, Anatsui’s body of work explores inconsequential objects used in bartering that had little value or meaning for Africans. With majestic, powerful and thought-provoking scale, Anatsui posits Africa’s embattled relations with materiality where foreign objects were used as a divisive strategy by Europeans.

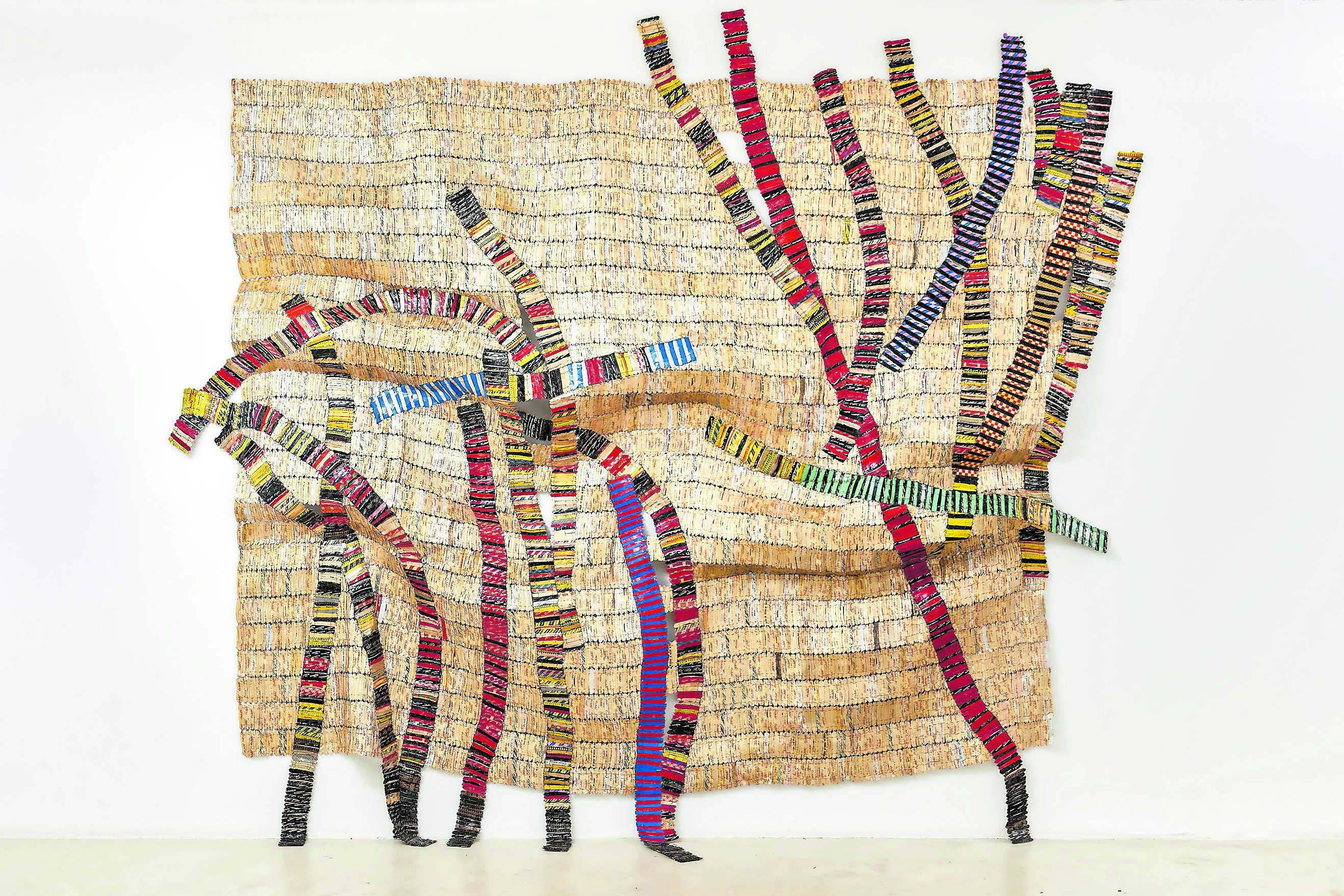

[A journey: El Anatsui’s Tsu is included in Meyina, the exhibition at the Goodman Gallery]

In the decade following the biennale, Anatsui has become one of the most sought-after and widely collected contemporary artists in the world. His works tour for years, gracing permanent collections at some of the most endowed museums and cultural institutions, including the Museum of Modern Art, the Pompidou Centre in Paris, the Akron Art Museum and the Denver Art Museum.

El Anatsui has eluded African audiences and galleries for years because of the perennial demand of his touring exhibitions, which last several years, such as Gawu, Gravity and Grace: Monumental Works by El Anatsui. But now the Goodman Gallery in Johannesburg has brought Anatsui back home; his first solo exhibition in Africa will feature the artist’s sculptural installations, works that push the boundary of what’s possible in artistic practice and use of materials.

Meyina, which means “I am going” in Ewe, is curated by Bisi Silva, director of the Centre for Contemporary Art, Lagos. It features seven large-scale works composed of thousands of compressed pieces of discarded alcohol bottle-tops — which he finds near his home — bound together with copper wire.

Silva says the intention of this exhibition, which travelled from the Prince Claus Fund Gallery in Amsterdam, was to go beyond El Anatsui’s works and introduce audiences to the person behind them with a selection of archival material from his studio. This material includes personal objects such as letters, exhibition planning documents, books he reads and is featured in, as well as articles written on his practice and exhibition publications.

This demystified the artist in ways that made me see his previous work anew. As one reads some of the hand-written letters and correspondence to different institutions one can see that the success he has received was not overnight.

From his letters — inquiring about artist residencies, packing lists for shipment of his work, back-and-forth communication about the prices of his works — it feels all too surreal, as if one is having a conversation with the artist.

This is one of the most compelling aspects of the exhibition. It feels like a learning opportunity from the father of contemporary art.

[The beauty of bottle caps: Tse by El Anatsui is a part of the Meyina exhibition]

This new frontier is articulated by Silva, who says: “In this exhibition, I hope to highlight aspects of his artistic practice as well as his professional career as a university professor and its impact on several generations of artists, curators and writers from Nigeria, West Africa and across the continent.

“I spent three or four intensive days looking through all these materials for this exhibition. What emerged for me is a portrait of the artist over the past 40 years — an artist who is still rooted in the narratives of everyday people and their history, engaging the local as artist, mentor and educator, much of which he continues [to] this day.”

Luminous and weighty, meticulously fabricated yet malleable, the artworks stretch one beyond the conventions of sculpture and painting.

At a distance, one is immediately drawn to the scale, form and aesthetic of the clothlike sculptures. On approaching the works, they begin to reveal and unravel a history of trade and materiality rooted in the slave trade and colonial expansionism into Africa, where resources and people were exchanged for bric-a-brac, mirrors and kettles or consumables such as alcohol and tobacco.

This powerful narrative is explored in artworks such as Fia (2014), in which alcohol bottle-tops are flattened and shaped to resemble fleets of slave ships that left the Gold Coast.

Anatsui takes us on a journey to explore different connects and legacies of colonialism. As I walk and think through this exhibition, my intuition leads me to a literal reading of the works I can’t seem to escape.

I feel pins on my feet as I get closer to Oases (2016), but my favourite piece, Tsu (2016), reminds me of Martian lands encountered by Africans when they got to the Americas — its topographical feel is almost unsettling yet equally magnificent and majestic.

[Monumental artwork: Resolution by El Anatsui showcases the artist’s lack of limitation]

To take something as simple as a discarded bottle-top and reimagine it as a monumental artwork steeped in history is something that continues to excite me about El Anatsui. His depiction of history as past and present, lingering and suspended in the very spaces we move through as socially engaged people, is one of the most exciting aspects of seeing his works. It’s an experience.

Rather than reading like a retrospective of Anatsui’s work, Silva curates an exhibition that journeys into a post-coloniality marred by an uneasy, complicated relationship with alcohol, one that is intricately woven into the very fabric of our society.

Although Anatsui leaves particular aspects of the exhibition, such as the hanging of the artworks, to the curator (his only preference being the works have horizontal ripples), the interpretive consistency is astounding because no two curators or institutions have ever installed the sculptures in the same way.

Mirroring post-colonialism, whether with academic framing or the actual lives of the people who discarded these bottle-tops, Anatsui forces one to go a bit further than the aesthetic rigours of art towards a personal dialogue that grapples with the presence of history in our everyday lives.

Much like Anatsui — who picked up a bag of discarded material from a local distillery in Nsukka, Nigeria, and, instead of seeing waste, pondered the complex lives that had touched and discarded the bottles-tops — it is hard to overlook the irony of these artworks as they hang on white walls in institutions around the world.

I look at the artworks as post-colonial collective identities, residues of energy carried by people, some of whom are just like us. Anatsui’s bottle-tops are a subtle reminder of the post-colonial effect, not unlike the bottle of Coca-Cola that fell from the sky in the film The Gods Must Be Crazy and tore a civilization apart.

El Anatsui’s exhibition, Meyina, runs until December 20 at the Goodman Gallery, 63 Jan Smuts Ave, Parkwood, Johannesburg