Not ready yet: Namisa Shembe

Perhaps the greatest irony about the recently deceased Nazareth Baptist Church leader, Inkosi Vela Shembe, is that it was only in death that the world was forced to reckon with the work he did to restore the stature of the church.

Last week mourners and church members gathered to pay their final respects to Shembe, who had only recently been found to be the legitimate leader of the Ebuhleni church, following a six-year court battle. He died after a struggle with cancer.

His work was done out of the limelight, say those who were close to him, among the worshippers who followed him out of the gates of Ebuhleni, where the largest group of believers in Isaiah Shembe’s gospel have their headquarters.

A few had been at Vela’s side at his cousin Inkosi Vimbeni Shembe’s funeral in 2011. There, in April of that year, the leader of the amaQadi, Mqoqi Ngcobo, disrupted the programme to make the surprising announcement that Mduduzi Shembe, Vimbeni’s son, would assume the role of leader. Ngcobo pre-empted Vimbeni’s lawyer, who was to have announced Vela as the new leader.

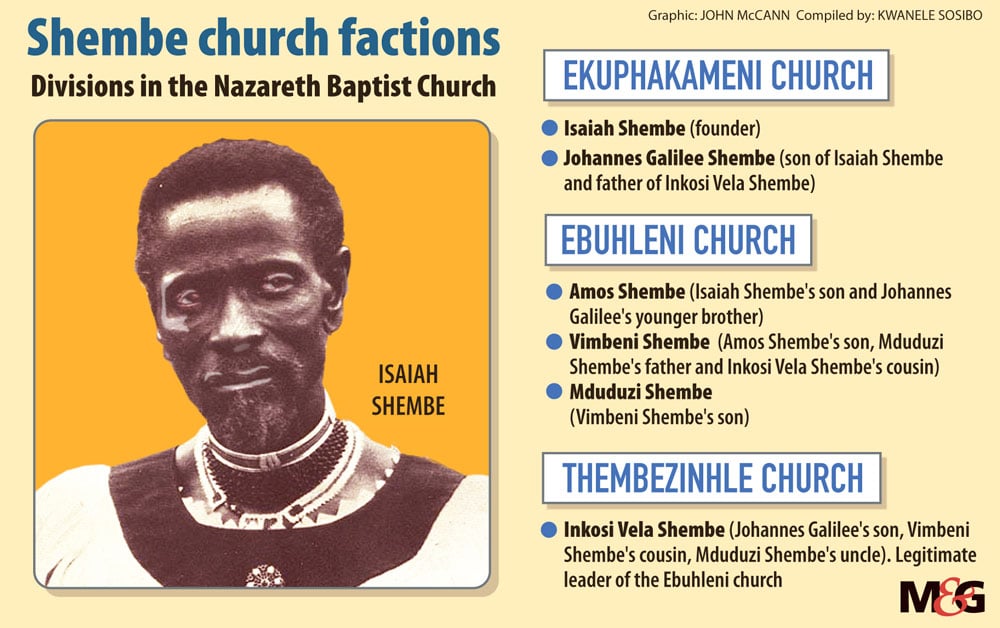

It was an action that would send the millions-strong Ebuhleni branch into a tailspin, eventually splitting it into two. But it was an uneven split, and Vela had to build up his Thembezinhle group practically from scratch.

A teacher by profession, Vela had been similarly instructive among his Thembezinhle flock. The group, which steadily grew in numbers, was based in Mtwalume on the KwaZulu-Natal South Coast. There was also a significant satellite temple in Inanda, which, perhaps symbolically, was situated between Ekuphakameni and Ebuhleni.

Ekuphakameni, on the southern edge of Inanda, is where church founder Isaiah Shembe first set up camp in the second decade of the 1900s and Ebuhleni is in the heartland of Inanda, where Isaiah’s third-born son Amos Kula Shembe had presided over a growing breakaway group since the 1980s.

Ebuhleni was formed following a disagreement between Amos and his nephew, Londa Shembe, after the death of Isaiah’s first successor, Galilee Shembe, who was Vela’s father.

[Heritage: With the Thembezinhle group opting not to immediately announce a successor to their deceased leader, Inkosi Vela Shembe, his send off was a decidedly sombre affair, unlike Inkosi Vimbeni Shembe’s 2011 burial. (Matt Kay)]

On the witness stand in 2013, the church secretary under both Amos and Vimbeni, Chancey Sibisi, told the court that Isaiah had named two of his three sons as his consecutive successors at a ceremony on the holy mountain of Nhlangakazi, years before his death in 1935. This claim, that both Galilee and Amos were his bona fide successors, is central to the legitimacy of the Ebuhleni house. Although much of the church history has been variously documented by historians, it is the subjective and often contradictory oral versions that are closely held and peddled by the believers.

A different version of the Ekuphakameni/Ebuhleni story, for instance, posits that no such ceremony took place in Nhlangakazi, meaning that Amos forcefully took the reins after his elder brother’s death, sparking a violent resistance that forced him out.

Whatever the version, many see the splits as a fulfilment of Isaiah’s prophecies, which may or may not explain Vela’s purist bent.

The predominant line of discourse at Vela’s funeral was that he had urged a return to simplicity, turning his back on the trimmings of modernisation in much of the church’s praise and worship, and constantly preaching an adherence to the strict asceticism for which the Nazarenes had been known. The church advocates teetotalism and has prescripts about food, many of which are based on the Old Testament. The singing, too, ebbs and flows like the wind (spirit) itself, without being scripted and rehearsed. For example, Vela was against the keyboard that was introduced to the musical repertoire of Ebuhleni’s proceedings as it altered the unfettered approach the Nazarenes took to worship.

“eNazaretha siyahlabelela, asiculi [In the church we sing based on our emotions as opposed to merely singing according to a scale],” says Hlumela Shembe, an elder brother to Vela from the Mtwalume base Vela had called home since the mid-1970s.

Hlumela grew up seeing Vela at times when their father, Galilee, “had devised ways” of bringing his numerous offspring together. He also says, unlike previous church leaders such as Amos and Vela’s predecessor Vimbeni, Vela took great pride in the church’s ceremonious dancing (ukugida), often joining the regimented groups in going through and refining the steps.

Hlumela, who bears a resemblance to his younger brother, says Vela’s austere approach to rebuilding the church was a brave move. It is a sentiment echoed by former Umzinyathi District mayor James Mthethwa, whose parents met and married in Ekuphakameni, where Vela spent part of his childhood.

[(Matt Kay)]

[(Matt Kay)]

“He revived the soul of the church in a very short space of time,” says Mthethwa, who is an MP, of Vela’s six years at the helm of the Thembezinhle group. “And he did this during a very challenging time in the history of the church, when people were challenging whether he was really appointed as the leader by the previous king Uthingo [Vimbeni].

“I was there in court when the verdict was announced and the judge confirmed him as the nominated leader of the Nazareth Church [the majority faction based at Ebuhleni]. He said he was glad that Uthingo had been vindicated after being portrayed as a man who would nominate two leaders. He didn’t take the glory for himself.”

These praises, some of which are justified by hearing Vela speak in YouTube clips, point to how this succession may be the most delicate of all. A lot will ride on the shoulders of the incumbent, and not all of it boils down to work ethic. Most speakers at Vela’s funeral recounted stories about his manner with people, how he had a special ability to make you feel uniquely valued without making the interaction seem false.

Explicit talk of succession at these delicate times is regarded as being insensitive and sensationalist. At the funeral, church spokesperson Nkululeko Mthethwa was his usual inscrutable self, appearing a little bit overwhelmed by the media spectacle, when he said an announcement would be made on December 16.

What is clear is that the leadership will remain in Vela’s and his siblings’ generation. Vela’s eldest son, Namisa Shembe, was at pains to declare himself ineligible when introduced to me at the funeral on Sunday. Unprompted, he cited his “business mind” and a temperament that lay elsewhere, before quickly sidling off.

Some people are suggesting that one of Vela’s brothers, particularly one with whom he developed a close bond during the taxing court case, could be next in line. His academic pedigree is seen to be in keeping with the tradition established by Galilee, although his immersion in all matters liturgical is seen by some as being late in coming.

Whoever emerges as Vela’s successor knows they have huge shoes to fill, although the path has been well prepared for them.

At a meeting on Wednesday, it was raining heavily. Sibisi listened to my circuitous questioning patiently and answered sparingly. When all was said and done, he pulled out two documents. One was of prescripts Vela had been updating and the other of farming projects and co-operatives he had been planning to realise.

It made me think that, whoever takes the helm of the church, which has the legal rights to assets and trust accounts worth hundreds of millions of rands, will best serve if they widen the church’s network of self-reliance and self-upliftment.