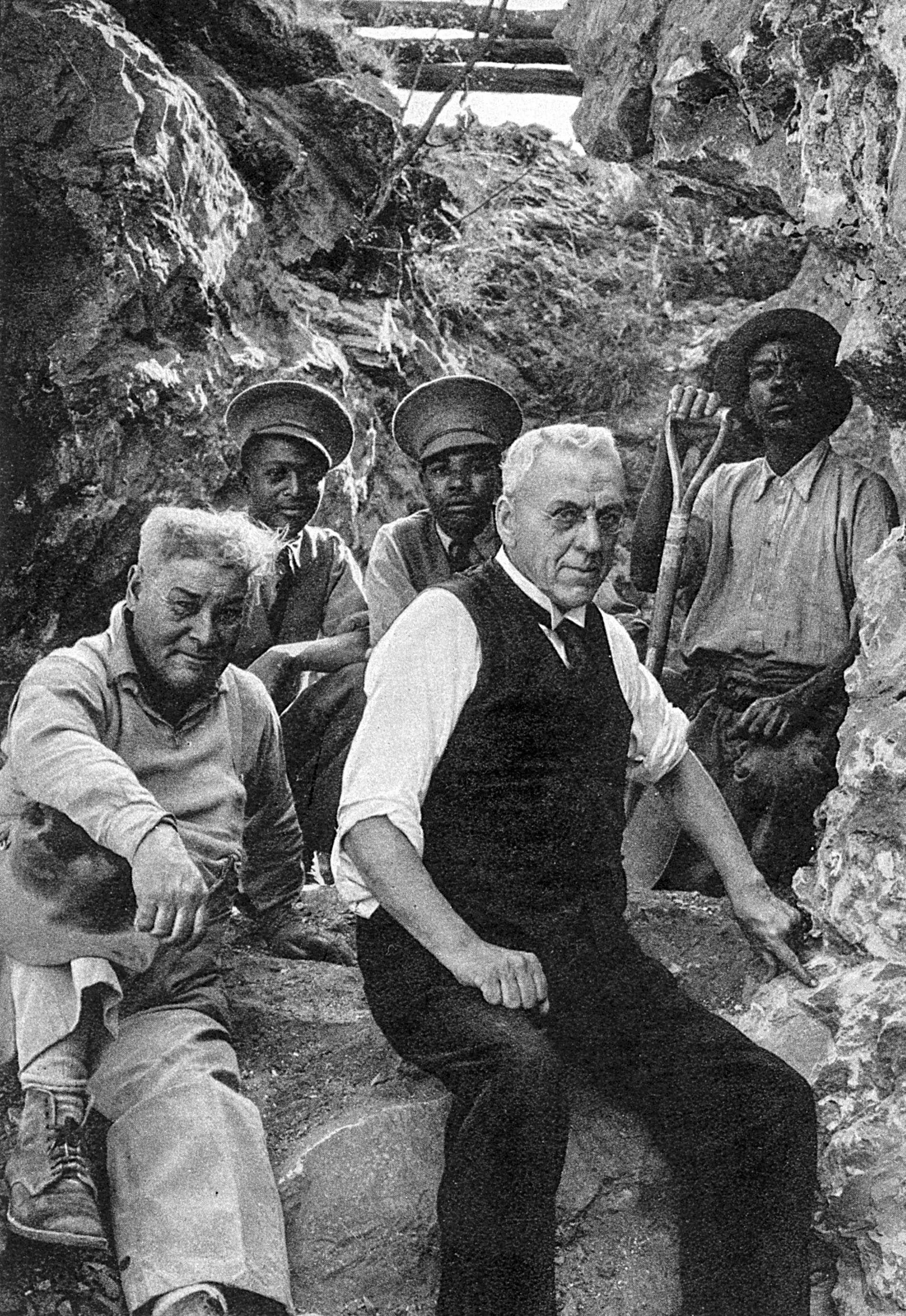

Digging for clues: Ron Clarke, Stephen Motsumi and Nkwane Molefe were equally recognised for finding Little Foot. Photo: Kathy Kuman.

In July 1997, Stephen Motsumi and Nkwane Molefe descended into the Sterkfontein Caves with a small tibia (shin bone) to see whether they could find where it had originally broken off during mine blasting 70 years earlier. After many hours in the damp darkness of the cave, searching the muddy walls with only a small headlamp, Motsumi’s eyes got tired.

The first day yielded nothing. On the second day, Motsumi and Molefe returned to the task, standing for long periods, using their fingers to clear away mud, looking for bone. After several hours, Motsumi found a place where the small bone in his hand matched a broken bone in the wall of the cave.

In keeping with his calm demeanour, Motsumi kept his surprise to himself. But when Motsumi and Molefe brought Professor Ron Clarke down into the cave to show him the spot, Clarke’s hands were shaking. He knew they had found the skeleton of an ancient prehuman ancestor embedded in the rock.

Twenty years later, on December 6 2017, the display of the full Little Foot skeleton at the University of the Witwatersrand is the latest public event that has placed Wits at the epicentre of a complicated mix of science and politics over the past century.

It is impossible to separate science from its social and political context, especially in this city, where the earth still trembles, reminding us of a buried history.

After gold was discovered on the Rand in 1886, men from rural areas and neighbouring countries left their families for the City of Gold to look for work on the mines.

In 1894, an Italian miner named Martinaglia opened a small quarry at Sterkfontein. He found limestone, which is needed for gold processing, and a few years later, he blasted through the rock and found the Sterkfontein Caves below.

In 1925, when Raymond Dart was the head of the department of anatomy at Wits, his description of the Taung Child skull as Australopithecus africanus made him and his university famous worldwide in palaeoanthropology.

His fame and his association with this 2.5-million-year-old fossil would not have happened had there been no mining under way in Taung. The mine managers were blasting for lime, but scientists asked them to keep an eye out for fossils as well.

Back at Sterkfontein, Robert Broom — Dart’s colleague, Wits lecturer and world-renowned palaeontologist — decided to explore the cave for fossils as well, hoping that it might hold treasures similar to Taung. In 1936 and 1938, assisted by the mine manager and several labourers, he found hominid fossils.

On the back of a photograph taken with Broom in 1936, there is no information about the “quarry boy” with the spade, nor about Jacobus the “museum boy” to his right.

[Robert Broom shows where a fossil was found in Sterkfontein Caves in 1936. His caption identified the others as Mr Barlow, two ‘museum boys’ Saul and Jacobus and a quarry boy (Illustrated London News)]

This pattern of giving workers and assistants little recognition would repeat itself and help to initiate the myth of one man, one fossil.

Many scientists like Dart and Broom, as well as Jan Smuts, South Africa’s prime minister, were interested in the study of ancient, three-million-year-old fossils as well as the study of living people in Southern Africa, and often blurred the lines between these two distinct areas of learning.

At the time, the derogatory colonial term Bushmen was in common usage and scientists and anthropologists often treated people as specimens to be studied. Smuts and Dart described the residents of the Kalahari as “living fossils”.

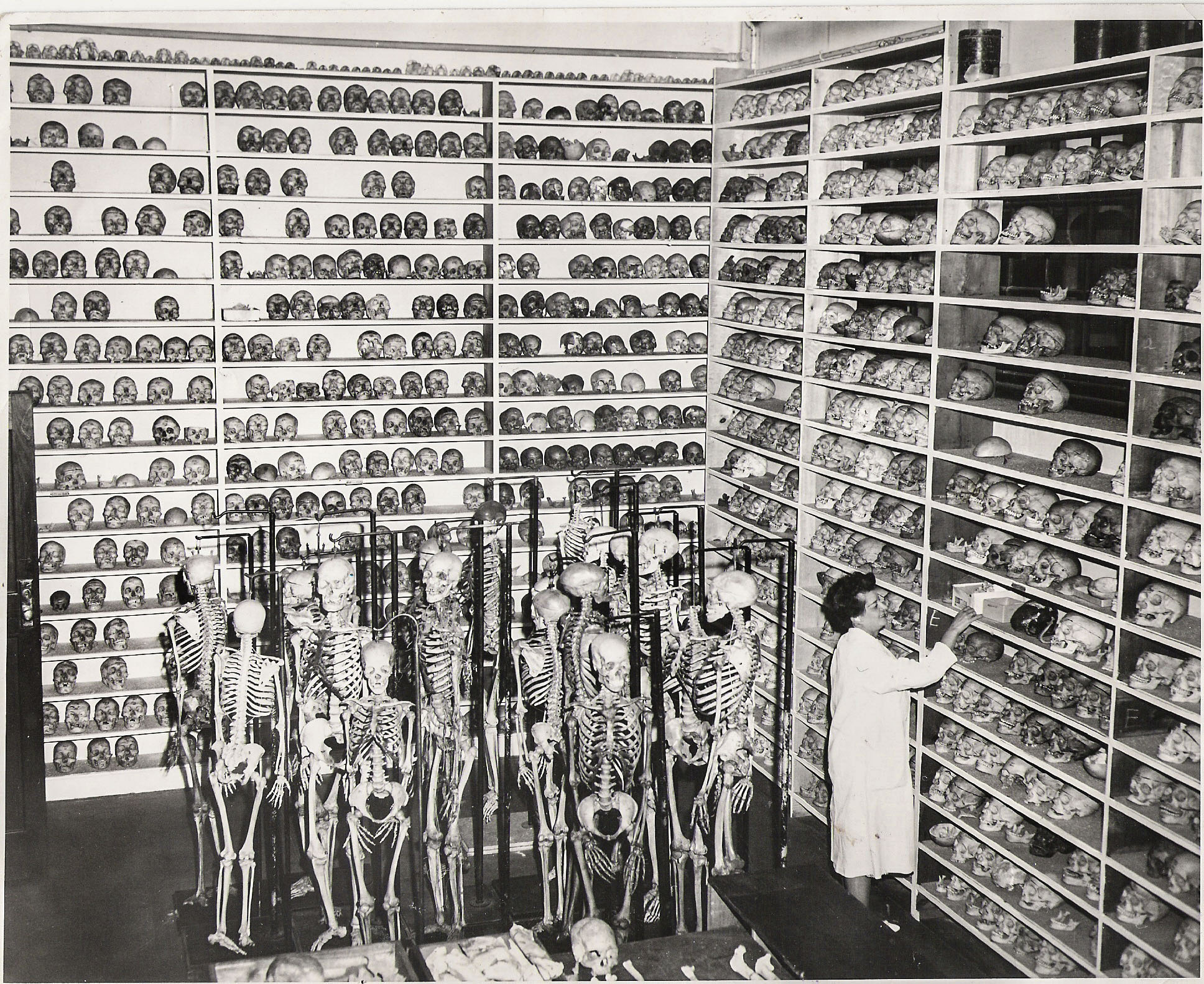

Broom gathered “Bushmen” skeletons, often in nefarious ways, and regularly sent them to British universities as part of a thriving skeleton trade.

Dart was also interested in the anatomy of the “Bushmen” because, as did many of his peers, he mistakenly believed that there were distinct and pure racial types. Many scientists promoted the idea of a racial hierarchy and white supremacy. Dart thought that, if he understood the “Bushman” anatomy and the pure “Bushman” racial type, it would give him a clue to human evolution.

Wits scientists continued the search for ancient human origins in the Sterkfontein Caves and Broom returned there in 1947 and, with the assistance of John Robinson and Daniel Mosehle, he blasted through the rock. When the dust settled, he uncovered an adult cranium of an Australopithecus, now widely known as Mrs Ples.

Although the full Little Foot skeleton was displayed to the world for the first time in December 2017, the story of its discovery dates back to Dart’s successor, Phillip Tobias.

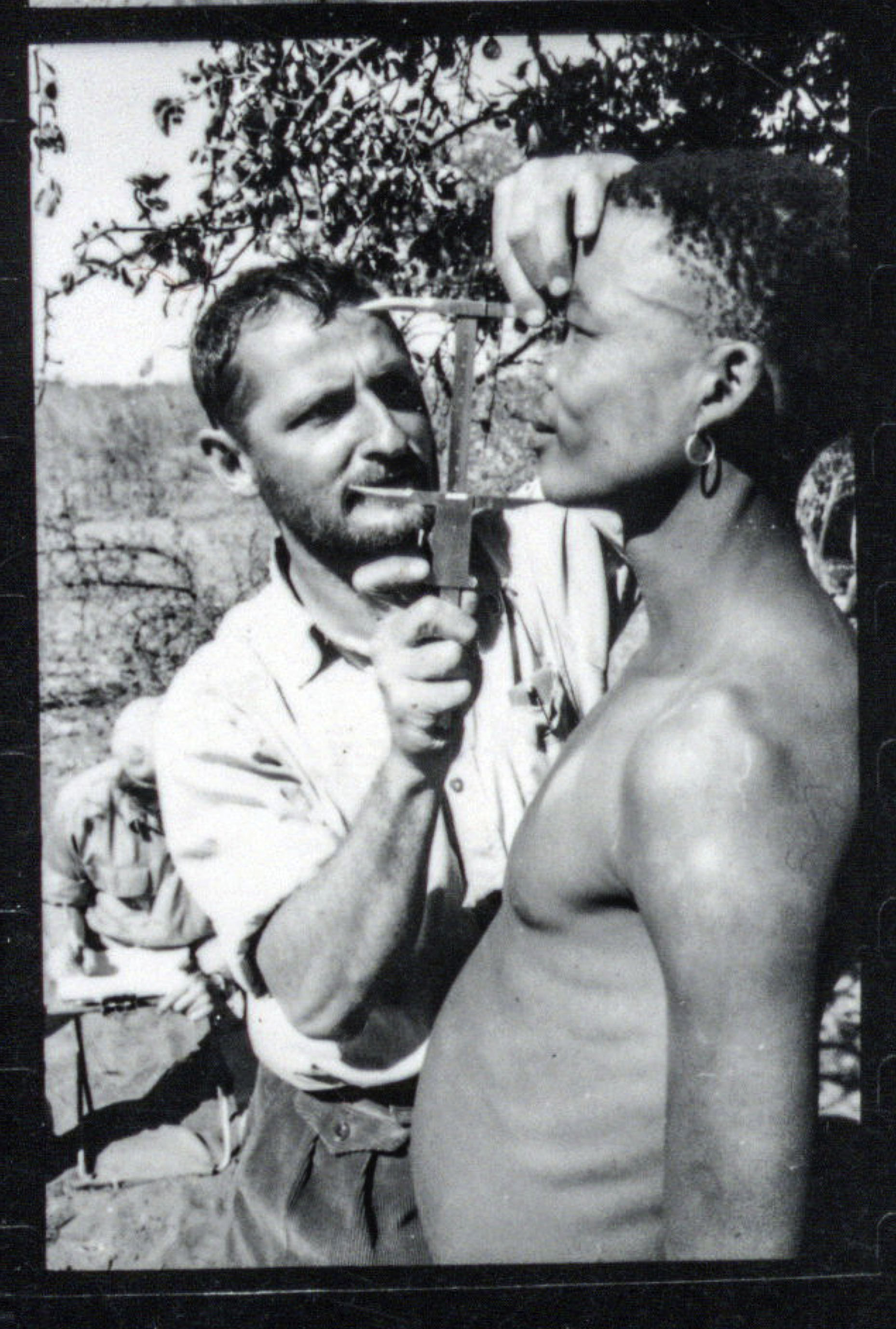

[Phillip Tobias, measures a ‘Bushman’ in the 1950s. His anti-apartheid stance clashed with anthropological practice (University of the Witwatersrand)]

Tobias had been a student of Dart’s in the 1940s and was inspired by Broom’s work at Sterkfontein. He was shaped by the effect of World War II and the introduction of apartheid and began writing about “the meaning of race”.

Tobias was more politically active than his predecessor Dart, and he became known for his leadership role in the National Union of South African Students and his public support for black students at Wits.

But, following in his mentor Dart’s footsteps, Tobias spent much of the 1950s making expeditions to the Kalahari. He too wrote about the “Bushman” anatomy, believed in race typology and continued anthropological work that included gathering face masks, taking invasive anatomical measurements, and exhuming skeletons to build the Raymond Dart Human Skeleton Collection.

In the late 1990s and 2000s, Tobias declared that “we are all one human race”. But decades earlier, he had believed that “race” described distinct scientific categories, which in many ways paralleled the apartheid classifications at the time.

Tobias never fully reconciled his anti-apartheid views with his problematic anthropological practices.

In 1966, with the support of Wits University, it was Tobias who re-opened the Sterkfontein Caves for excavation. Almost a decade later, Tobias took a young PhD student, Ron Clarke, into one section of the cave where there was a lot of rubble that had been dynamited out by mineworkers many years earlier. Along with the head of excavation, Alun Hughes, Tobias arranged to have the fossil-bearing rubble (called breccia) brought out of the cave.

The manager of a nearby goldmine agreed to send a team over to construct a platform with a ladder and a hoist. It took three years to carry out all the rock. Some of the fossil bones found in the breccia were then put away in brown cardboard boxes in a storeroom at Sterkfontein.

[The Raymond Dart Human Skeleton Collection in the 1960s (Goran Strkalj)]

They sat there for 14 years until 1994 when Clarke decided to take another look. He took countless plastic bags out of one box and set them on a table under a lamp in the storeroom. Patiently, he opened each bag and checked all of the bones inside.

After days of work, looking through countless bags in multiple boxes, Clarke found one talus bone that caught his attention in a bag marked “monkey foot bones”.

He took the bone home over the weekend to show his wife, archeologist Kathy Kuman, and said: “That’s not a monkey. That’s a hominid.” Three years later, Clarke found several other hominid foot bones that convinced him to search for the full skeleton in the cave.

We don’t quite know what life was like for the labourers who pulled the breccia out of the Sterkfontein Caves. And we can only wonder what happened to Broom’s assistant Mosehle.

Years later, on December 9 1998 at Wits University, Clarke and Tobias announced the Little Foot skeleton fossil find to the world. Unlike many technicians and labourers in the past, Motsumi and Molefe attended the press conference and Clarke credited them for their dramatic find.

The Sterkfontein Caves and some of the surrounding land is now owned by Wits University, but there are other privately owned farms in what is now known as the Cradle of Humankind.

For decades, the myth of the empty land was perpetuated, and historians claimed that no one had lived in this part of the country until the Boers trekked inland from the Cape.

In the 1970s, Wits University archaeologist Revil Mason wrote about settlements that thrived in the area as long as 1 500 years ago. Sesotho- and Setswana-speaking people had inhabited the area and left substantial architectural remains.

Today historians ask why Mason’s research was ignored for so long and why he was harassed by some and ignored by others for much of his career.

Johannesburg, the Sterkfontein Caves, and the Cradle of Humankind, as well as Wits University, will continue to be at the centre of this field, not only because of Little Foot, but also as a result of the work of Lee Berger and his team, and the findings related to Homo naledi and the Rising Star cave system not far from the Sterkfontein Caves. As this work expands, it is critical that Wits broaden the network of scientists involved by training and supporting young black South African students entering this field, especially young black women, and recognise labourers and technicians for their important contribution.

Christa Kuljian is the author of Darwin’s Hunch: Science, Race and the Search for Human Origins (Jacana 2016), which was shortlisted for the Sunday Times Alan Paton Award for Nonfiction in 2017