Kasi glory: Kwesta

My parents etched out a comfortable existence for our family in the imprecise terrain that often forms in the fissures between working and middle class life in black communities.

Our home carried with it the many aesthetical contradictions of this class ambivalence. This meant that our tiny eyes were trained to see in excess. Our kitchen cupboards were packed to the rafters with AMC and Hart pots, Pres Les crockery and a boundless supply of ceramic and enamel dishes along with nondescript Tupperware of every design and colour.

The display cabinet in the dining room was held together by our school portraits, report cards, trophies, participation certificates, books, dictionaries, yellowed telephone directories and expensive plates and tea cups reserved only for the dining pleasure of important guests. Pink and white crocheted covers centred our elaborately designed sofas, which were complemented by unobstructive cushions in between every seat.

Minimalism was certainly not the name of the game as more and more decorative objects in the form of orange and pink porcelain ornamental dogs, romantic-styled murals and wedding and graduation photos peppered various parts of our living area.

Despite the many disparate bits and bobs, the house I grew up in and still call home never felt cluttered or aesthetically incongruous. It was an expression of the kind of eclecticism that I have found in other black homes across the class and spatial divide in Southern Africa.

When I first watched Kwesta’s latest music video, Spirit, I was reminded of this eclecticism that existed on its own terms.

The cinematic experience of this music video is a celebration of black life in all its different permutations. Of course, given that Kwesta announces “ukuthi sizomthola ekasi lakhe” on a sofa covered with a thin film of plastic in the first few frames of the video, the viewer is given a clear indication that the next set of images account for an expression of life in Katlehong, the township east of Johannesburg where the hip hop artist hails from.

That said, there is something of the essence of South African blackness that is finessed by filmmaker and directorial genius Tebogo Malope in this piece.

Disparate vignettes of black people making their way through their days shoot back and forth as the video starts. A camera pans across a set of houses. Each house holds its own distinctive choice in paint colour, brick colouration and tile design. Black palisades account for the fencing for most of these homes and then a yellow capitalised font tells us that this is Kwesta’s Spirit featuring Nigerian-American rapper Wale.

[Kwesta with Nigerian-American rapper Wale, who is featured in his 2017 track Spirit]

Against the backdrop of a graffiti portrait of Nelson Mandela, a man paces up the road as if he is making his way to catch some form of public transport. Words such as “RIP”, “visionary” and “Izwe Lethu” litter this wall, making it an informal tribute and public memorial of our former statesman.

In the very next frame, in another kind of memorialisation, Kwesta dons a number 11 T-shirt in honour of soccer player Emmanuel “Scara” Ngobese.

Before Kwesta leads us into the sitting room that is so reminiscent of home, two men are found in a river mid-baptism — a familiar story of one brother leading another into salvation and to reach their eternal home in the heavens.

[A priest is seen praying in a river with a congregant, mid-bapitsm, in Spirit ]

Malope sets up some of the dominant themes and aesthetic signifiers as the spirits of the dearly departed and the Holy Spirit are introduced in lieu of the song’s deliciously ambiguous title.

The vignettes continue to spiral into a world that is constantly unravelling the idioms and idiosyncrasies of black life in its heterogenous splendour.

Young children hold and throw buckets filled with water and joy at one another. A man exhales the smoke of his blunt. Another man lifts his hands in prayer and another looks up from a pile of debris and dilapidated walls. A chicken is slaughtered ceremoniously. And then, the K1 Gawd, Kwesta.

As he promises in the first verse of his multi-platinum selling hit released in October of 2017, simfica echillile ephethe ezinye zakhe, ke ke ke. His iconic tone, a kind of deep rumble, sits nonchalantly atop a carefully crafted beat punctuated by ad libs and amafluit.

[Tebogo Malope behind the scenes (Modirapula/Amacreatives.com)]

The song itself is an anthem of sorts, an ode to the hustle and a clarion call to all to not give up or lose focus of whatever dreams they might have.

In a tweet from December 17 last year, Kwesta writes: “You won’t read columns about how we took Black Consciousness to the top of the charts. It’s an anthemic dance song but the message addresses the state of a nation in distress from desperation to inspiration then aspiration, do you have the #Spirit?”

Malope’s choices in the music video seem to mirror these sentiments; he plays with different articulations of desperation, inspiration and aspiration and reworks what all of those different categories might look and feel like.

[Tebogo Malope with Kwesta, behind the scenes of Spirit ()]

Fire, for example, is a thematic device that is returned to often. Perhaps the most talked about image from this video is the young black man burning the old South African flag. In the frame before, he stands with a tyre around his neck. Immediately images of necklacing, a torturous form of killing reserved for those who had “betrayed their people and communities” to the apartheid police, are dragged up in our collective consciousness.

The burning man, who is better described as an adolescent, stands defiantly as the flag catches flame around him. It’s perhaps a reminder that the systemic infrastructure of apartheid still has material consequences for the lives of millions of young black people. His defiant stance is an expression of resistance.

Later on, in a different sequence, a man sits among broken buildings and rubble engulfed by flames as he drinks from a Heineken bottle. Across from him is a taxi that has also been set alight. The image of the man has an eerie resonance with some of the xenophobic attacks that consumed parts of Gauteng in 2008 and again in 2015. Ernesto Nhamuave is a name that haunts South Africa’s moral consciousness. He was a Mozambican burnt alive by South Africans guarding with bigoted angst their claim to their fledgling nationality.

[An eerie resonance with the 2008 and 2015 South African xenophobic attacks]

Fire continues to frame images of repression. We see orange bonfires behind a scene where a group of policemen is arguing with a crowd of almost exclusively young men. Violence seems imminent. Desperation in this sense is not just a conversation about hopelessness but perhaps how that sensibility can engulf those it takes hold of in ways that can be destructive.

One of the final fire images is of a young woman pulling a red suitcase that is burning. Her dreams either seem to be set on fire in that kind of millennial vernacular where we throw around fire/flame emojis at everything we deem cool, beautiful or extraordinary — or her dreams have been scorched into oblivion.

Water seems antithetical to the desperation foregrounded by the images of fire and people burning. Water seems redemptive; the man who has been dunked into the river for baptism stands triumphant as he emerges. Children in high spirits play water-games with delightful abandon on the streets of Katlehong.

Most of the women in these vignettes seem to operate within the logic of a definitive binary between temptress and saint, old and young, morally questionable and morally sound. Cut-away shots of women performing their desire and desirability are speckled with disembodied shots of a woman’s thighs glistening in pink lighting. Some imbibe various alcoholic spirits.

On the other end of the spectrum, older women in blue and navy church uniforms perform the rites of religious practices. The video juxtaposes an image of a woman accepting the Holy Sacrament with one of a group of women downing alcoholic shots. Soon afterwards, an image of a collection basket with a handful of notes and coins in it is passed around and the next shot is of a man in a club throwing money around in the say way that men throw money at exotic dancers.

The contrasts are stark and the images are in quick succession of one another. The commentary is implicit but not necessarily subtle.

In other shots we see a mother holding her child in a way that mirrors ‘the African Madonna and Child’ portrait that is a ubiquitous image across rural and black urban centres.

The video is a tapestry of significations that are, at their core, South African but are not distinct from a pan-African set of experiences and images. For example, the scenes in the taxi rank are similar to the iconography that we see in Wizkid’s Ojuelegba. Wale in a shweshwe-like hoodie stitched together with patterns of the former president of the United States, Barack Obama, is a nod to a globalised black identity — even if it is, within the context of that moment, based on a brief fashion choice. Nigerian-American musician Jidenna even offers his brief solidarity to “the spirit”.

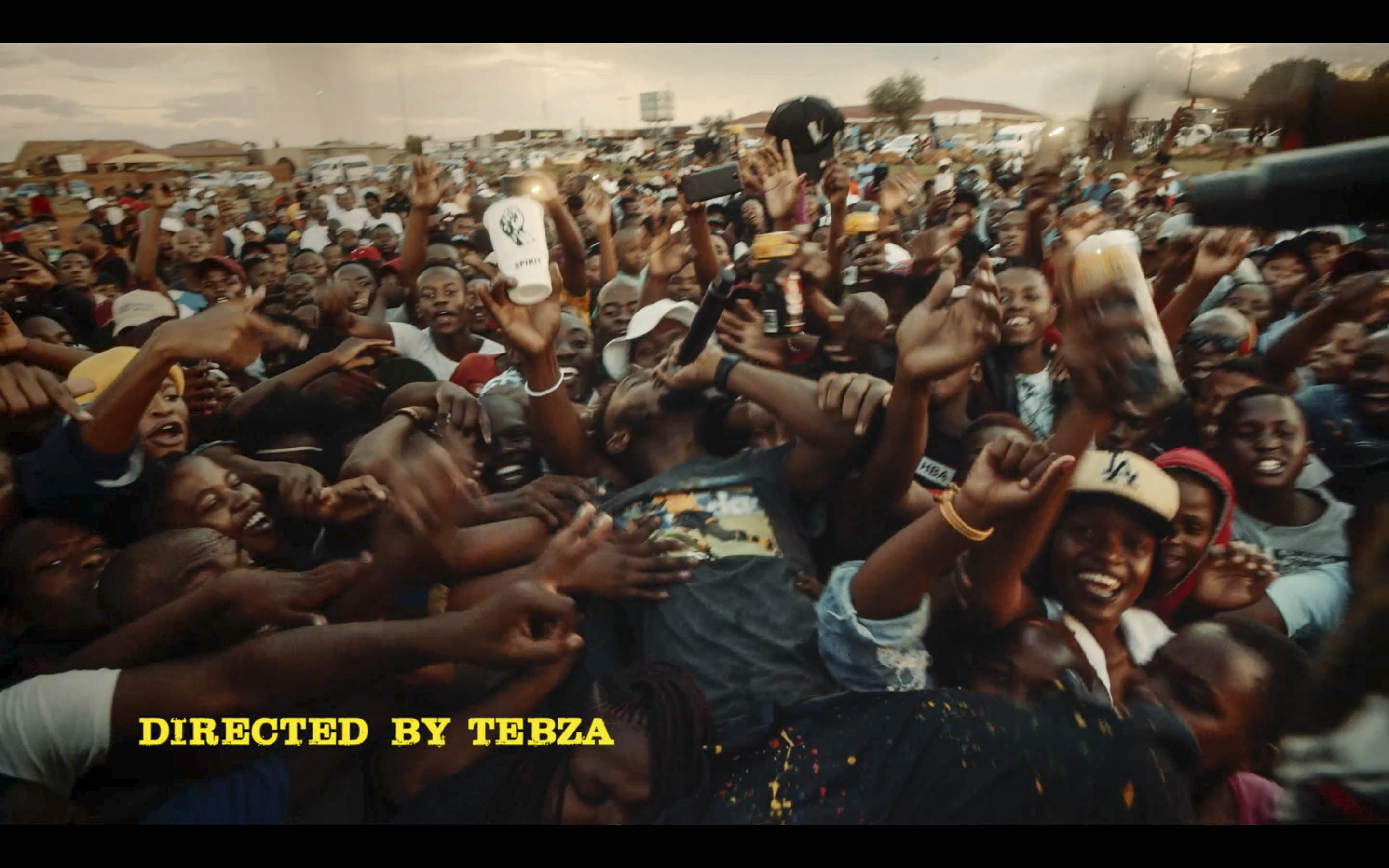

In only four minutes, Malope covers an extraordinary amount of ground. The video is bursting with visual inferences that are familiar and nostalgic. Little snapshots of “us” bob and weave into one another in a way that overwhelms and titillates the senses. The archive of black visual representation collated by these artists is nothing short of extraordinary and it will take several more careful watches to distil and appreciate every single moment. For now, we celebrate what it is to have our homes reflected back to us. Spirit!

Production team for Spirit

Director- Tebza

Executive producer- Gavin Joubert

Producer – Marc G Harrison

DP- Tom Revington

Art director – Gavin Skates

Editor – Andrew Traill