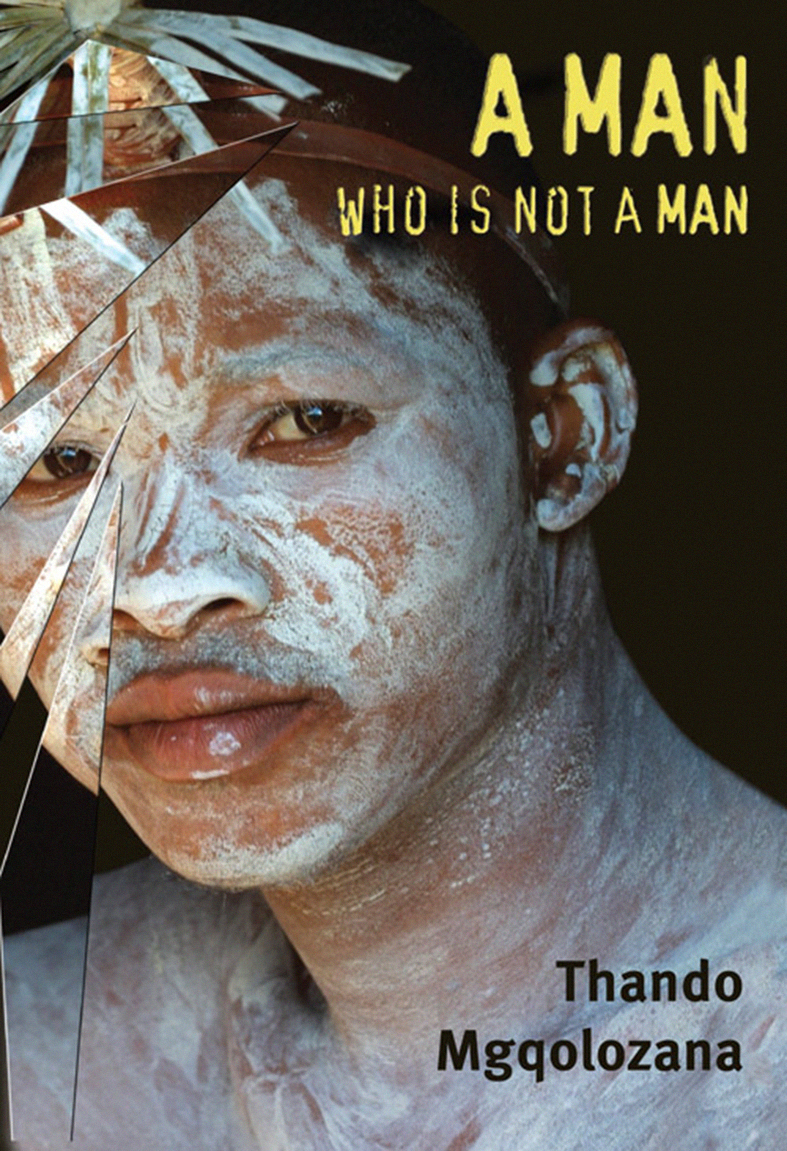

Tradition: Xhosa initiate Fezikhaya Tselane

In 2010 before the World Cup, I and nine other writers travelled to eKoloni for four days to donate books and talk literature with the audience, a journey that took us to places like eBhayi and eRhini.

eRhini, we had a discussion at Rhodes University where we encountered two affable young Xhosa brothers, who we would meet again on our final morning while having breakfast. They had been at our talk in the library the day before and looked forward to reading our books. Well, all our books, except for one, which, they said vehemently, they would not read: Thando Mgqolozana’s 2009 debut novel, A Man Who’s Not a Man.

[Thando Mgqolozana’s debut novel ‘A Man Who is Not A Man’ was shunned for disrespecting isiXhosa culture.]

“So why don’t you want to read that one?” I asked.

“Because,” one spat, “this guy,” pointing at Mgqolozana, “is disrespecting our culture.”

Siphiwo Mahala rushed to diffuse the situation by asking: “But how do you know it disrespects our culture if you haven’t read it?”

They had no response.

Months later just after the 2010 World Cup, I would host a book club session of about 12 women who had read the book, with the author present. What was interesting is that both non-Xhosa and Xhosa women appreciated the novel and thought it would start important conversations about injuries and deaths during ulwaluko.

On the other hand, Xhosa women who were not mothers were offended by the book. Not because they did not feel that it spoke some home truths but because they, like the young men eRhini, felt it disrespected and exposed their culture, and felt any conversations about it should be discussed privately as “a Xhosa nation”.

It is not just Xhosa men who are guilty of protecting oppressive aspects of a culture by avoiding the criticism of outsiders. This is because women have also been trained to uphold patriarchy.

Mgqolozana’s novel, published in 2009, had a likeable protagonist in his senior year of matric. During ulwaluko, for lack of an attentive khankatha, his penis fails to heal properly and he finds himself in a hospital ward with other injured bakhwetha and a nursing sister who mockingly sings the circumcision song Somagwaza to them as she nurses them.

Interestingly, this book was published in the same year that the SABC pulled the screening of a documentary, Right of Passage, because then president of the Congress of Traditional Leaders of South Africa, Phathekile Holomisa, was unhappy about it being shown. Like Mgqolozana’s novel, it was said to disrespect our culture.

But what Holomisa failed to be outraged about was that the subject of the documentary, University of Cape Town student Buntu Majalaza, had suffered blood poisoning after ulwaluko, which resulted in his death. He joined many other young men who have lost their lives, or, if lucky, end up with disfigured penises after every circumcision season.

But the traditionalists would rather we not voice our anger about this needless loss of lives. They would rather let our brothers and sons die or suffer botched circumcisions in silence. Unless, of course, we express our anger in our regional newspaper, the Daily Dispatch, before we get on with our lives and let the same cycle be repeated in the next circumcision season.

On Friday February 2 this year, I read that a film I have been looking forward to watching, Inxeba, is causing a furore and will not be shown eKoloni and in parts of the Western Cape. As the day progressed, and indeed over the weekend, the anger voiced over this movie became louder and louder, and some of it from people like musician Loyiso Bala, who as an artist one would expect to be a defender of free speech.

The loudest voices accused the movie of cultural appropriation. I sighed. The movie is co-written by Mgqolozana and Malusi Bengu, stars Nakhane, Bongile Mantsai and Niza Jay Ncoyini, has abantu as the make-up artists and a black co-producer, Batana Vundla. How then, is it that amaXhosa had culturally appropriated their own culture?

It then became obvious that every Xhosa man who was making a noise about it on my social media had not watched the movie.

In defiance of this sort of ignorance, I decided I was going to watch it and invited as many friends as could make it on social media to join me. I am a Xhosa woman. And there is nothing I saw in that movie regarding ulwaluko that I did not already know happens.

It is a beautifully written, shot and screened story of the toxic masculinities that are created and encouraged, even in same-sex relationships. It questioned a manhood that is intolerant of any boys who are not “manly men”.

Contralesa secretary, Chief Mkhanyiseli Dudumayo, is quoted as saying: “But if they are saying to us that is what happened to them, we are open to say they must share with us and say we are experiencing this. My traditional surgeon was so and so, he romanced me. So that we can speak what they have experienced.”

Obviously there is at least one chief who did not watch the movie and made assumptions about it based on a trailer. Because, madoda, anyone who has watched it will tell you that the story actually is about two khankathas who are attracted to each other but have to hide what they feel for each other. And a mkhwetha who is comfortable enough in his skin that he does not understand why his khankantha cannot be “man enough”, so to speak, to be comfortable in his own skin.

In a country that has always celebrated diversity, Inxeba asks of Xhosa men whether they are able to welcome people who are queer, or whether they have to hide their sexual identity if they too want to take part in ulwaluko. It gives Xhosa men an opportunity to have an important conversation on homophobia.

Man and Boy Foundation executive director Nkululeko Nxesi complained: “The entire film gives a bad impression of initiation schools. There are explicit sex scenes and it also shows people falling in love. Sex and romantic relations are not part of activities that take place in the mountain.”

Firstly, romance happens in the craziest of places. No one can dictate where sex and romance can or cannot happen. Secondly, there are no explicit sex scenes in the movie, or explicit circumcision scenes, or, or, or.

Finally, if a film shows people falling in love and the executive director of Man and Boy Foundation thinks this is wrong, one wonders what his foundation is teaching boys. How can love be wrong?

There are places without water eKoloni and eKapa. Women who are raped and abducted. Children raised by single mothers, without males who came down from mountains as men. There is corruption eKoloni resulting in third-rate schools and hospitals. Oomakhulu who have to raise orphaned children on an old-age pension. But your collective outrage, fathers and brothers, stems from a movie that shows men loving each other.

I am a Xhosa woman who is raising a Xhosa boy. If this is your manhood, madoda, keep it. Your priorities are very skewed. Art demands that you engage with it before you criticise it. I’m talking to you too, Loyiso Bala.

Mama ka Hintsa

Zukiswa Wanner is a South African author based in Kenya