Expenditure will be cut in various areas. Fee-free higher education will go ahead.

A desperate need to fund the budget has led to desperate measures. Although a hike in VAT and other taxes have stolen the show, a plan to slash expenditure by R85-billion over the next three years is also a drastic move.

Expenditure will be cut in several areas and reprioritised to fund, among other things, the mammoth commitment to provide fee-free higher education for students from disadvantaged households. This accounts for the largest budget reallocation — R57-billion over the medium term.

But the finance minister is no Robin Hood. The poor households who stand to benefit from free higher education will be hit by the trade-offs required to fund it.

The treasury’s estimates of national expenditure show that “learning and culture” received the biggest upward adjustment of R59.3-billion, mostly for free higher education. Community development was the biggest loser, with a R29.7-billion net decrease, mainly because of cuts in grants for housing and infrastructure, electrification and transport.

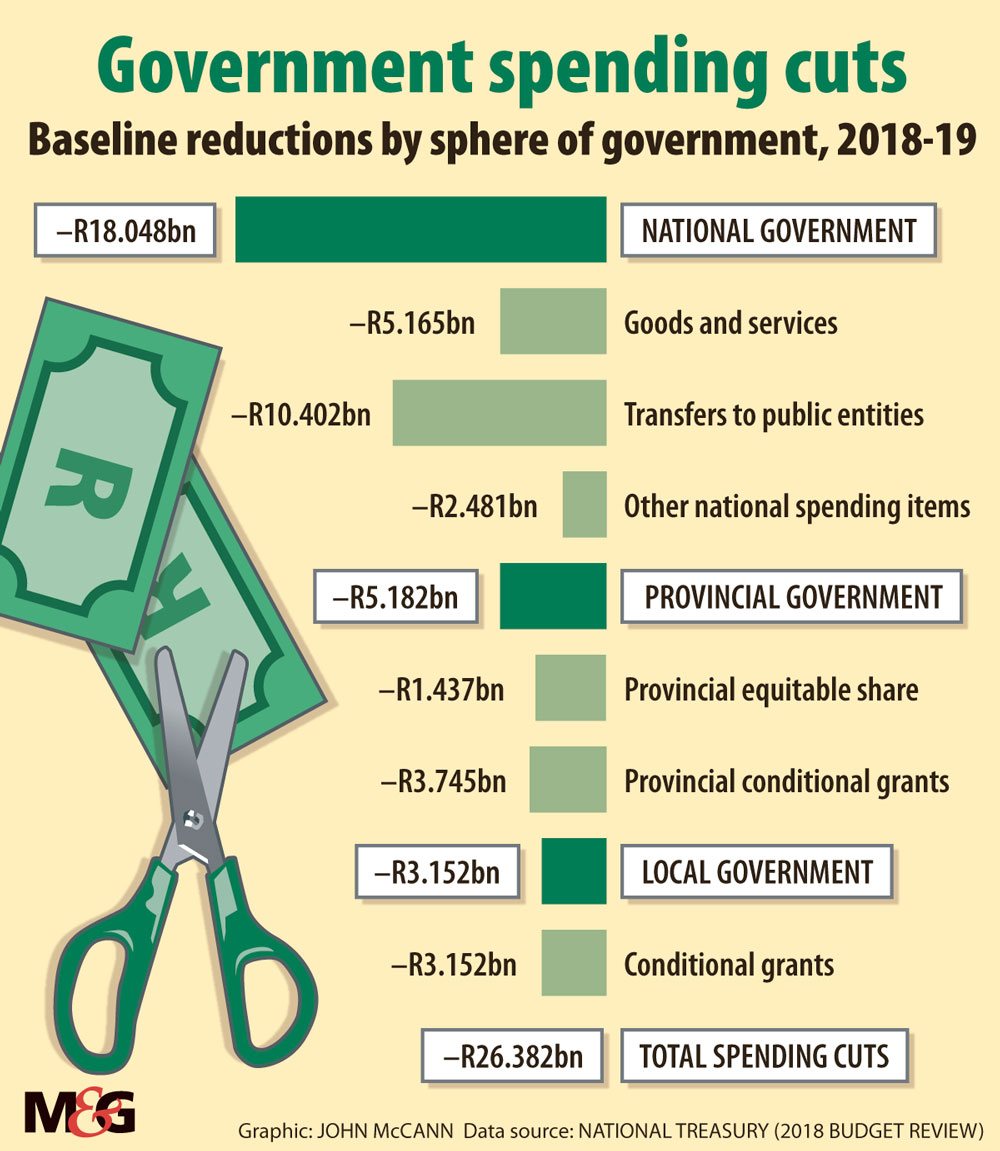

Although public spending will reach R1.94-trillion in the 2020/2021 financial year, this is still a cut of R85-billion from departmental budgets over three years, starting with R26.4-billion in 2018-2019.

For starters, all national and provincial departments are required to cut their spending on administration. But the cuts fall mainly on large programmes and transfers to government entities.

In terms of monetary value, the biggest cut — R29-billion in total — will be in transfers to public entities, including the South African National Roads Agency Limited, the South African Revenue Service, the Passenger Rail Agency of South Africa and four water boards. In terms of percentages, local government grants will suffer the biggest reduction — 9.3%.

According to the budget documents, allocations were reduced to large programmes, including the department of defence’s special defence account and air defence programmes, the correctional services’s incarceration programme, and trade and industry’s manufacturing development incentives.

At provincial and local government levels, funding for initiatives such as school infrastructure backlogs, electrification of households, the development of urban settlements and public transport networks are cut.

“These cuts will delay the completion of a number of infrastructure projects,” according to the budget review.

Treasury director general Dondo Mogajane said there were also other programmes where “efficiency gains must still be squeezed”. For example, R570-million was taken away from the treasury’s jobs fund because of underspending.

At a provincial level, conditional grants were cut by R13.7-billion over the medium term. For example, the education infrastructure grant, which has a history of underspending, will be reduced by R3.6-billion and will result in some projects being deferred. The human settlements development grant is reduced by R7.2-billion and will slow the delivery of new houses and serviced sites.

But some of these funds will be reprioritised to create emergency housing grants intended to improve responses to housing needs after disasters. Other grants suffered small cuts because of poor performance.

For local government, R16.1-billion was cut in funding for direct and indirect conditional grants. The most substantial cut was to the municipal infrastructure grant, according to the budget review.

But, Mogajane said, funding for most programmes would still grow above inflation, despite the cuts.

Mike Teuchert, the national head of taxation at Mazars, said the cuts appeared to be on infrastructure spending rather than on day-to-day operational costs, such as the bloated public sector wage bill.

Expenditure on staff and salaries, accounting for 35% of government spending, will not be reduced but is expected to grow by an average of 7.3% each year.

As has become the norm, the cost of servicing debt is rising, which limits the treasury’s spending. According to current trends, the government is expected to spend 12.2% of available revenue on servicing debt by 2020-2021.

“Of course, we would like to be able to allocate more to each sphere for service delivery and a larger share to local government,” Finance Minister Malusi Gigaba said in Wednesday’s budget speech.

“But the reality is that the rising cost of servicing our national debt leaves less resources available to invest in services across all three spheres of government.”

A new item, the National Health Insurance, will receive a budget of R4.2-billion over the next three years.

This will not be funded from reprioritised money but from ring-fenced funds raised from savings achieved by increasing tax rebates for private medical aid contributions at a rate lower than inflation, which the finance minister announced.