Breaking Barriers:Lwanda Sindaphi's Kudu

December 1 2016

I sit in the Magnet, an old match factory turned theatre, as the wind crashes on to the roof and cars can be heard from time to time speeding way too fast down the narrow lanes of Lower Main Road in Cape Town. Inside, Kudu is about to begin, and I can just about make out the director, instantly recognisable in his signature peak cap and floral print sports jacket. The lights are turned down and darkness creeps up on us. On stage is a table placed on top of a mound of sand.

This is how Kudu entered my life.

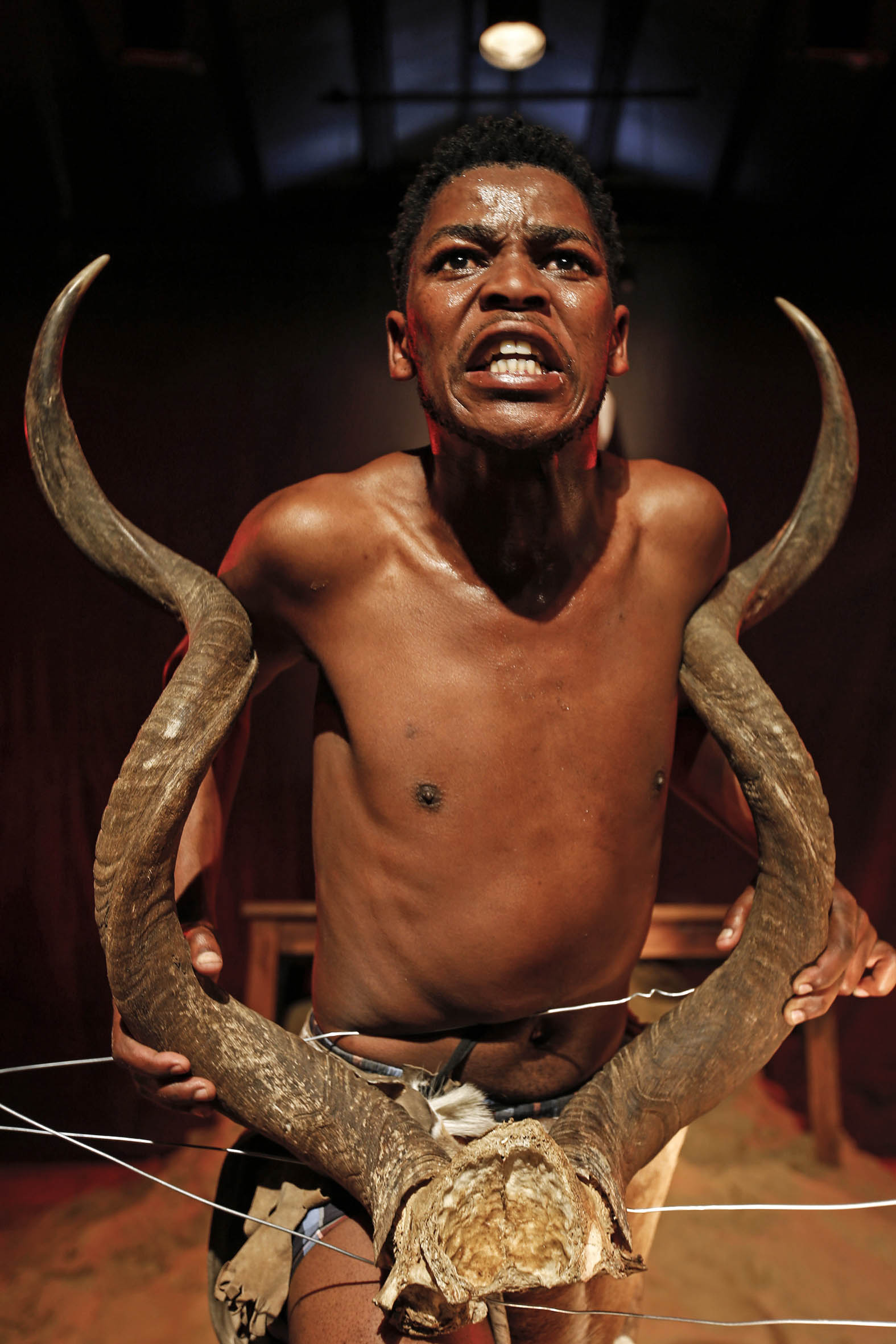

[Lwanda Sindaphi’s production Kudu (#VulturePhorography)]

Kudu is written and directed by Lwanda Sindaphi, who created it in the Magnet Theatre Internship programme. It begins with the fulfilment of Nongqawuse’s prophecy: it is 2030 and the British settlers have been driven back into the sea and AmaXhosa rule the Eastern Cape. Three Khoi descendants travel to Ntaba kaNdoda to take back the land that had belonged to their ancestors before Chief Ndoda was killed centuries earlier.

When asked about Kudu, Sindaphi said he was inspired by the notion of a spiritual genocide as described by David Robbins in On the Bridge of Goodbye: “The genocide of consciousness, of language, of culture.”

February 2018

Sindaphi and I sit in the Baxter Theatre, him again in his signature cap. Speaking to him now it becomes clear that Kudu is a story about boundaries and the way they are challenged and shifted.

Sindaphi tells me about one of his favourite scenes in the play. A Khoi man is hunting kudu. The hunter stands behind a screen, his shadow projected on to a brown screen. Images of rock paintings are immediately evoked. The hunter follows the kudu to the front of the screen. A wire fence appears and the kudu runs into a nature reserve, which the hunter is unable to enter.

“There was a video that I watched before I created Kudu,” says Sindaphi, “and many of them [the kudu] died because they couldn’t go out of the reserve. They would die there. There’s this thing of the body wanting to move but it can’t because somebody owns the land, owns the space. There’s this longing of ‘I want to be there. I want to go there, but I can’t’. The kudu wants to come back into the landscape but it can’t, because there are colonial fences. Even the Khoi people want to come back and make themselves visible but they can’t because there are colonial fences.”

[Kudu is a story about boundaries and the way they are challenged and shifted (#VulturePhotography)]

The fence is not a physical barrier that prohibits access to land but one that affects how we interpret history, culture, language and, ultimately, ourselves.

Throughout the play the Khoi tell AmaXhosa to listen to the stones. According to Sindaphi: “That’s where the history of the Khoi is. They listen to the drawings because the ancestors speak through the stones.”

Set against the story of Ntaba kaNdoda and the fulfilment of the long-contested prophecy of Nongqawuse, Kudu calls for an acknowledgement and legitimation of multiple knowledge systems. These multiple ways of reading are infused elsewhere in the play.

The play itself is dialogue heavy but it is a hybrid that purposefully refuses to be fenced in. Sindaphi writes in an English born of his Xhosa upbringing and infuses the rest of the script with isiXhosa and Afrikaans.

Even the visuals seem to move as they shapeshift under the gaze of the audience. An example of this is the table on the mound of sand around which the action of the play revolves. It is at once the mountain, a symbol of the land, a negotiation table, a space to discuss political disputes, and a dining table — a shared space for family members and symbolic of the negotiations done in the personal space.

March 29 2017

I am sitting in a University of Cape Town lecture theatre listening to Lwandile Fikeni’s talk, Like a Pistol Shot in the Middle of the Concert.

The talk grapples with the role of art and literature in articulating new ways of being in a post-Truth and Reconciliation South Africa. At one point Fikeni questions the preference of appealing to a collective identity over an individual identity, how this collective identity is used to justify the actions of an individual and how it also works to erase the complexity of the individuals who make up the collective, where an unintended homogenisation then occurs.

Once again I am reminded of Kudu.

[The production questions the legacy of prominent groupings in South Africa such as AmaXhosa (#VulturePhotography)]

The play is the dissection of a homogenised blackness. Kudu at once foregrounds the antagonism, erasure and ignorance surrounding the Khoi heritage, while questioning the legacy of prominent groupings in the country such as AmaXhosa.

February 2018

My writing revolves around blackness and identity politics. My social media timeline is filled with conversation and commentary on love, black history and, now, the brand-new Marvel superhero film, Black Panther.

Twitter has told me that all black people are residents of Wakanda, an isolationist African country revered for its technological advancements and education system, and is subsequently one of the richest countries in the Marvel cinematic universe. Black Panther is supposedly a collective Afro-futuristic dream that has already been hailed for its representation of a multitude of blackness.

But February 2018 is also the month that Kudu returns to stage. Considered next to Black Panther, I am excited by the questions that Kudu asks us, as South Africans.

Beyond fictional imaginations of the future, are we able to dare to imagine a future for ourselves grounded in our lived reality?

Kudu is at the Baxter Theatre until March 10