All-star exhibition: Works by Picasso and Bonnard and Matisse

In the trade dispute between the world’s two largest economies, could China have found its trump card — the humble soybean?

In retaliation to United States President Donald Trump’s plan to impose high import duties on Chinese steel and aluminium imports, China has threatened to retaliate with similarly high duties on 106, mostly agricultural, US imports, such as pork, maize and soybeans. It’s aimed to hit Trump where it hurts most — his core constituency.

Iowa, Nebraska, Indiana and Missouri are major producers of soybeans — the most valuable export to China last year — and all states voted for Trump in 2016. Iowa, for one, for the first time in 35 years, planned to plant more soybean than maize, but now farmers are concerned; the planting season in the Midwest and Delta regions begins this month. The farmers, have begun to lobby against the US trade policy. And Republican representatives in agriculture-producing states are torn over how to handle the matter.

(John McCann/M&G)

Experts anticipate retaliatory duties on soybeans will be devastating, though Trump has said he will “make it up” to the farmers. He has threatened to impose duties on a further $150-billion worth of Chinese imports.

The US and China soybean markets are closely linked, Wandile Sihlobo, an agricultural economist and the Agricultural Business Chamber’s head of agribusiness research, says in a note.

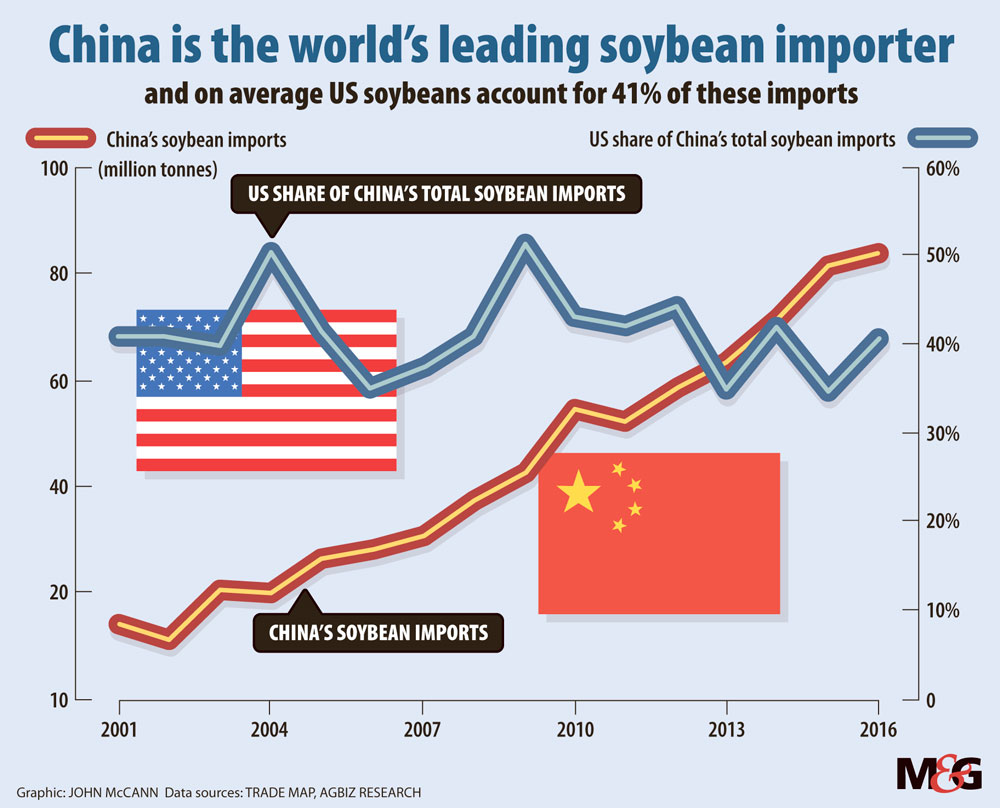

“Firstly, China is the world’s leading importer of soybeans. The key underpinning factor behind the country’s appetite for soybeans is the growing demand from the animal feed industry. Secondly, China is the leading market for US soybeans exports.

“From the US perspective, China is an important market for soybean, accounting for an average share of 45% of all soybean exports in the period between 2001 and 2017. Over this period, the US exported an average annual volume of 31-million tonnes of soybeans to the world,” Sihlobo says.

According to data from the US department of agriculture, China’s soybean imports for the 2018-2019 financial year could reach 97-million tonnes — a 64% share of global imports, Sihlobo says.

The other leading suppliers of soybeans to China are Brazil, Argentina (usually the key supplier) and Uruguay. South Africa is a net importer of soybeans and soybean products, Sihlobo says.

“In the near term, the impact of the ongoing US-China trade dispute will be limited to the local soybean market, with the exception of the influences through the Chicago soybean price volatility,” says Sihlobo, referring to the agricultural derivatives prices, which are set by the Chicago board of trade but used as a benchmark internationally. Already the news of China’s retaliation last week saw soybean futures drop in price.

There are two disputes going on, according to Donald MacKay, a XA International Trade Advisors and Stratalyze director. “Trump’s official position is ‘the US has a huge trade deficit and this thing is a problem’ … there are a lot of questions around whether there is logic to that.”

Dave Mohr and Izak Odendaal, Old Mutual Multi-Managers investment strategists, say in a note that the record trade deficit is not a sign of US economic weakness but of strength, as improving domestic demand draws in more imports. US exports are also at record high levels.

Given how globally integrated the world is, by blocking imports from China, imports from other nations are likely to surge and so would do nothing to reduce the deficit.

Separately, there is a dispute over intellectual property. As part of a company’s investment into China, it must hand over its intellectual property, which the US is decrying.

“I don’t think this is simply going to disappear,” MacKay says. “China finds [itself] in a very difficult position if you look at the instrument the US chose to use.”

Instead of implementing duties in the way most nations do, Trump has made use of section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962, a Cold War tool that allows the US government to evaluate the effect of imports on national security. It has only been used in a handful of cases, Mackay says.

Although duties to block cheap steel on a product-by-product basis have been employed before, this is much broader, MacKay adds. It appears to be part of a bigger strategy, according to which “not only are the Chinese evil, so is the

WTO [World Trade Organisation]. Trump has problems with the WTO, and his using an instrument [that] doesn’t fit neatly in the WTO is like thumbing his nose at the WTO.”

The WTO is a rules-based system that favours smaller traders and prevents economic and diplomatic powerhouses from exerting undue pressure on others to get what they want. “And Trump doesn’t like that,” MacKay says.

Trump’s use of this instrument, which will come into effect in June, appears to contravene the WTO rule and, although China may take the matter to the WTO, “it will take far too long to resolve, [so] the odds of them not retaliating are very slim,” MacKay says.

Mohr and Odendaal say it is too soon to suggest that a full-scale trade war is looming. “There is still plenty of time for the two sides to iron out an agreement.

“Within each country, there are also powerful interest groups who would want to maintain the status quo.”

Although the US’s action on steel and aluminium is targeted at China, it affects the world, MacKay says. States can apply for an exemption and South Africa has done so.

Business Insider reports some organisations, such as Wesgro, the Western Cape investment agency, believe some South African agricultural exports, including wine, will benefit from China’s proposed taxes on certain US goods.

MacKay says, with US beef also in the firing line, South African beef stands to benefit because of an agreement signed last year. But, on balance, globally, a trade war will be negative. Already the JSE has taken a knock. The share price of the largest company on the board, Naspers, dropped because of its extremely lucrative stake in the Chinese internet company TenCent.

Markets tend to sell first and ask questions later, say Mohr and Odendaal. “The decline in market value of global equities has been in excess of $1-trillion since the tariff spat began, clearly an overreaction. Looking ahead, with each successive tariff announcement, the surprise factor will be less and market response should be milder.”

Nobody is able to assess the potential effect. “All the steel and aluminium travelling between China and the US will have to end up somewhere,” MacKay says, as will all American and Chinese exports blocked by either party.