Naloxone is cheap

Alexander Walley was a twentysomething medical student when he witnessed the power of naloxone. It was the midnight shift at the Emergency Department at Johns Hopkins Hospital in Baltimore, Maryland. The call wasn’t unusual: a middle-aged man had been found unconscious after overdosing on heroin. Walley accompanied a pair of paramedics to an ambulance, and they headed out into the cool moonlit night. After five blocks or so they arrived at one of the city’s housing projects and threaded their way across crumbling sidewalks to a shabby apartment in a dimly lit building. Inside, Walley found the man slumped against a wall, blue-skinned and not breathing. “He looked dead,” Walley says, recalling the incident 15 years later.

With the calm, sure movements of someone who has had lots of practice, one of the paramedics pulled a syringe from his bag and injected the man in the arm. Walley waited, unsure of what was supposed to happen. He thought he saw the man’s hand twitch. Then the blue began to drain from the man’s face, and his chest started to rise and fall regularly.

“What did you give him?” Walley asked.

“Naloxone,” came the reply.

Walley had heard of the drug, of course. He knew it as one of the few defences against the epidemic of overdoses that was killing people across America. Cheap and relatively pure heroin had recently become easier to obtain, but that wasn’t the only cause. A few years earlier, physicians had begun to change the way they prescribed opioid painkillers. These drugs can be highly addictive; one physician I talked to called them “heroin in pill form”. Yet between 1991 and 2013, prescriptions for opioid painkillers jumped from 76 million to 207 million per year, partly because physicians became more willing to prescribe the drugs to patients with chronic pain. Some of these patients found themselves hooked. And then, instead of sticking with these relatively expensive prescription narcotics, some began injecting heroin, for the better high and lower cost. America’s prescription opioid and heroin epidemics were merging into a single monster, one with tentacles that seemed to be everywhere, slowly strangling young and old.

Naloxone, which also goes by the brand name of Narcan, became a mainstay of hospital emergency rooms and medical wards during this time. It can be injected or sprayed up the nose, and can stop an overdose in under two minutes. It’s so vital the World Health Organization placed the drug on its list of essential medications in 1983. And though Walley didn’t realise it at the time, naloxone would become critical to his career. That night in Baltimore showed him that naloxone can save lives. Later, the memory of it would persuade him to take on a project that was laden with controversy and avoided by many of his peers. Walley would attempt to give tens of thousands of people – parents, police, even drug users – the power to reverse an overdose.

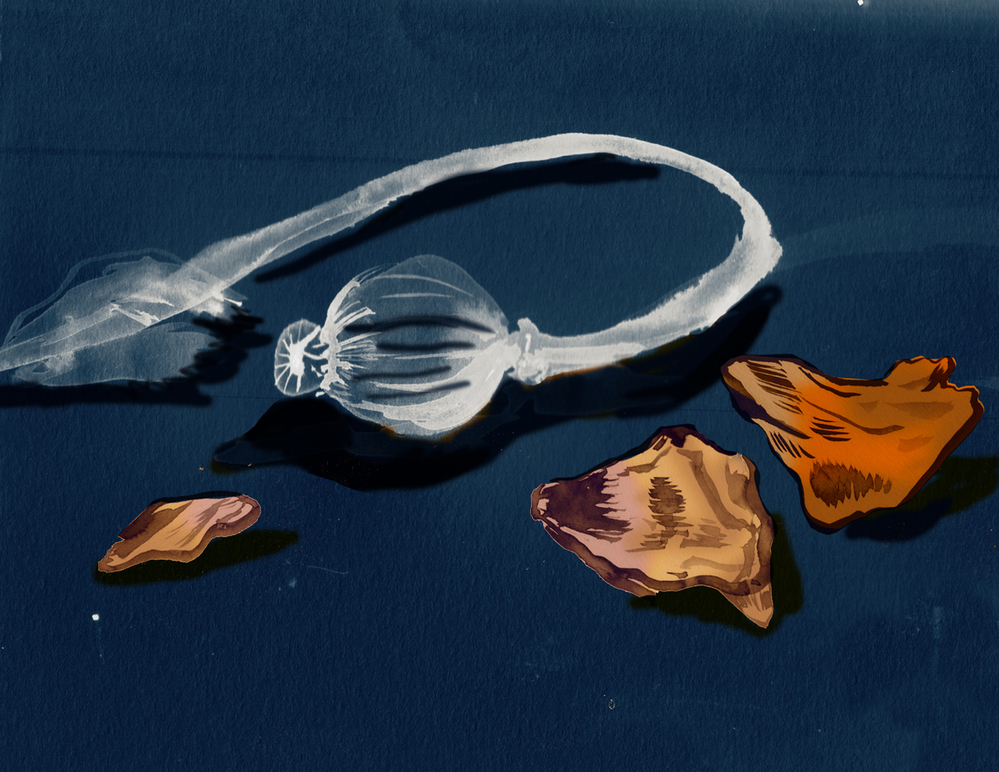

When heroin is cheap and flooding the streets, naloxone could mean the difference between life and death (Mari Kanstad-Johnsen)

Right around the time Walley saw a user survive, Dan Bigg was watching others die. One in five residents of the city where he worked – Chicago – were living in poverty, and the city had a serious heroin problem. Overdoses weren’t the only things killing heroin users, for sure. Other killers like homicide and HIV were taking lives too. But Bigg was seeing more and more drug users dying from overdoses, and he didn’t know how to respond.

It was the late 1990s, almost a decade after Bigg had helped found the Chicago Recovery Alliance with the aim of getting clean needles to drug users. He had quit a psychology doctorate to work with drug users. And the Alliance was working: the spread of HIV and hepatitis C among users had slowed. But overdoses were killing so many users that few lived long enough to succumb to disease. Some of those deaths were especially hard to take: in 1996, another of the co-founders of the Alliance had relapsed into heroin addiction and died of an overdose.

Heroin killed Bigg’s friend the way it kills other users. After entering the brain, the drug is converted into morphine, which binds to the body’s opioid receptors with an attraction so strong that it can remain locked in place for hours. Some of these receptors switch on the brain’s reward circuits – the same system that generates feelings of pleasure when we engage in activities like eating or sex. Others are involved in pain transmission; heroin causes these receptors to dampen down pain signals entering the brain from the spinal cord. But there are also opioid receptors on neurons that help control breathing. Take too much heroin, and these neurons will slow down respiration dangerously. Starved of oxygen, the lips and fingers turn blue. The person falls unconscious and stops breathing. Death can come within minutes.

Naloxone reverses the process by acting like a toddler grabbing for another child’s toy, preventing death by shoving the opiate out of the way and binding to the receptor itself. This sends the user into immediate withdrawal. The side-effects – dizziness, nausea, shaking, sweating – are unpleasant but not overly dangerous. And if someone hasn’t used any opioids, naloxone will have no effect, positive or negative.

After his co-founder’s death, Bigg began devoting more of the Alliance’s time and resources to overdose prevention, and he put naloxone at the heart of the effort. He wasn’t a doctor and couldn’t distribute naloxone, but he talked some physician friends into accompanying him on his visits to users, where they would prescribe and distribute syringes of the life-saving drug. It was a risky endeavour: because the drug would likely be administered by a friend of the user or a fellow user, not the person it was prescribed to, the prescription was legally questionable. But Bigg figured it was worth it if it meant that naloxone was on hand when an overdose occurred.

He focused on users who had overdosed in the past, since this was a strong predictor of future overdose, and his advice was simple. See someone not breathing or looking grey? Hit ’em in the thigh or arse with naloxone. If they’re not breathing, breathe for them by tipping their chin back, plugging their nose and breathing directly into their mouth. Then call 911. He began to carry naloxone himself, and has since used it six times to treat users, events he recalls as both scary and gratifying.

Starting in 1996, Bigg and his friends passed out handfuls of vials of naloxone and clean needles, then hundreds of them. He never had enough naloxone to go around, and at first didn’t even keep close records of how much he handed out. As soon as he got some, he gave it away. But as word of the programme spread, Bigg was able to get physicians to sign orders allowing him to distribute naloxone solo, and obtained private funding to purchase the drug. His on-the-fly operation appears to have been a success: even as drug use in the Chicago metro area increased, deaths from opioid overdoses declined by almost a third, from 466 in 2000 to 324 in 2003.

Naloxone can be sprayed up the nose or can be injected. (Mari Kanstad-Johnsen)

Almost a thousand miles to the east, Walley watched Bigg’s progress with no small amount of interest. After graduating from medical school he had moved to San Francisco to begin a primary care residency. He worked with some of the city’s most vulnerable people, and made a habit of listening as well as prescribing. Then, as now, he seemed an unusual candidate for such a task: bespectacled, dapper and softly spoken, he looked more like an English professor than someone who dispenses methadone to the homeless. Yet Walley’s patients liked to talk to him. They told him about their struggles and the tragedies they had witnessed. Often, it struck him just how little he could do to help.

After the birth of his two sons, Walley and his wife moved back to Boston to be near family. He worked out of a brightly lit second-floor office at a Boston University office complex, just south of downtown and directly across from the city’s largest homeless shelter. His new patients told him similar stories of addiction, trauma, homelessness and overdose. He saw people turn their lives around in rehab, only to do another one-eighty when they got back home. This cycle causes many addiction physicians to become jaded, but Walley has an unusually strong belief in the possibility of recovery. Still, he knew that if overdose rates continued to rise, some of his patients would not survive long enough to get well.

Then Walley begun to hear of Bigg’s success with naloxone. He understood the scale of the challenge his colleague was taking on, partly because he had been watching the opioid epidemic worsen in his own city. In the decade and a half after 1990, the incidence of fatal opioid overdoses had increased sixfold, to more than 600 a year. To reverse the trend, officials asked Walley to join a new programme to get naloxone overdose kits in the hands of active users and their family members. Walley says that there were other, more experienced physicians and researchers who might have been better suited, but they were either unable or unwilling to to take on the enormous professional risk that naloxone distribution brought with it. If the programme flopped, scientists would be reluctant to take Walley seriously in the future. And if naloxone caused harm, Walley could find himself legally responsible. Yet he agreed immediately. “There had been a spike in overdoses, and it seemed like a no-brainer to get these kits in to the people most likely to be on the scene, which was other users,” Walley says.

Like Bigg, the Boston officials started by targeting active users via the city’s needle exchange programme. In 2007 the head of the city’s health commission, John Auerbach, was appointed Massachusetts health commissioner, and decided to expand the programme to other parts of the state. To help do so, Walley signed a standing order that allowed certain public health employees to hand out naloxone nasal sprays without individual prescriptions.

To some, giving naloxone to users was not just counterintuitive but also counterproductive. Naloxone would allow drug users to run wild, knowing they wouldn’t die from an overdose. Bertha Madras, deputy drug czar to former US president George W. Bush, told National Public Radio that users shouldn’t have access to naloxone because “sometimes having an overdose, being in an emergency room, having that contact with a healthcare professional, is enough to make a person snap into the reality of the situation and snap into having someone give them services”. Madras told another reporter: “It is not based on good scientific data… It’s based on what some people would consider the right thing to do. But the studies supporting it are so sparse it’s painful.”

It wasn’t just political appointees who opposed naloxone. Community activists worried about having naloxone in their neighbourhoods; they believed that heroin users would flock to areas with such programmes. Even physicians had concerns. A survey published in the Journal of Urban Health in 2007 found that more than half of US doctors said they would never consider prescribing such a medication for fears that it would enable drug use – although less than one in four had even heard of take-home naloxone programmes.

Boston’s needle exchange programme, which goes by the name AHOPE, is run out of a low brick building around the corner from Walley’s office, in the middle of one of the city’s poorest and most crime-ridden neighbourhoods. AHOPE is a one-stop shop for the services users need: treatment referrals, information about detox centres, and whatever else might help them live their lives with health and dignity. Most of the people who visit are familiar with overdoses; surveys show that as many as 90% of injecting drug users have witnessed one.

Prior to naloxone, though, AHOPE could do little to help users treat overdoses. “Before 2006 we didn’t have this medication,” Sarah Mackin, AHOPE’s director, told me when I visited the centre this summer. “We didn’t have anything.” The only defence was a community of users who used together and looked out for each other. “They wanted to do something, anything, to save someone’s life. If it meant they were going to put ice on someone’s balls or put them in a cold shower, then that’s what they were going to do.”

The WHO placed Naloxone on its list of essential medications in 1983. (Mari Kanstad-Johnsen)

The WHO placed Naloxone on its list of essential medications in 1983. (Mari Kanstad-Johnsen)

In late 2007, Walley began helping AHOPE staff learn how to use and distribute naloxone. When a user came into AHOPE’s offices looking for clean needles, Mackin’s staff would be ready with naloxone and information about what to do in the event of an overdose. Mackin also told users about how overdose risk can change. “Your tolerance dips really, really quickly, even within a day or two of not using,” she says. “Folks come out [of jail or detox] and they go right back into the communities where they learned these behaviours, and that risk of relapse is so high.”

Before long, nearly everyone who came in wanted naloxone, and Mackin and her colleagues had to work double shifts to train the users in how to administer the drug. The effort paid off. A year after starting the programme, an internal analysis by Walley and AHOPE showed that users could effectively reverse overdoses. “Alex Walley is our hero,” Mackin told me recently. “He walks on water. He’s a saint for us. He was the only person that was here and willing to do this.”

Boston wasn’t the only area hit hard by heroin and resulting overdoses. In Quincy, a town just south-east of the city, parents of young opioid users began asking officials to get naloxone into the hands of first responders. Among those who supported the idea was Patrick Glynn, a gruff-talking 20-year veteran of the Quincy Police Department who began working with Walley and others. In October 2010, Quincy police became another prong in the state’s naloxone programme, and the first force in America where every officer was equipped with naloxone.

Over the next year and a half, the rate of fatal overdoses in the town fell by two-thirds. Glynn now likens the drug to the other medications in the police cruiser’s first-aid kit. “If we had someone that was allergic to a bee sting and had an epi pen, we’d help them, if they had a diabetic reaction, we’d help them with sugar or insulin,” he says. “We have a poison here that just happens to be called an overdose, and the treatment for that is the nasal Narcan.” Right now, adds Glynn, he and his colleagues are in an “unofficial contest” to see who can reverse the most overdoses.

Once word of Quincy’s success got out, other police departments wanted in. Glynn and other Quincy police officials toured Massachusetts, helping to train officers from large cities like Boston and tiny 10-officer towns. He also talked to police departments from Vermont to California. Cops in many towns around America now carry naloxone, and they will soon be joined by colleagues in New York City, where more than 19 000 uniformed officers are being taught how to use naloxone.

Parents, too, have clamoured for access to naloxone. One of the loudest voices has been that of Joanne Peterson, whose son became hooked on heroin after experimenting with OxyContin at a party in 2001. Three years later, Peterson started a parent support group called Learn to Cope. In 2007, workers from naloxone pilot programmes began distributing the drug at Learn to Cope meetings. By 2011, Learn to Cope had become a pilot programme in its own right, and its facilitators were training members in naloxone use.

Several times an hour, Peterson is interrupted by her phone – another desperate parent reaching out for support and information. Many are now also looking for naloxone. At Learn to Cope support groups in 15 locations around Massachusetts, she and other parent-facilitators teach members about addiction, how to help their loved one, and how to use naloxone. These parent groups have formed the third prong of Walley’s naloxone pilot programme. “We can barely keep up with the demand, there has been so many people coming to our trainings,” Peterson told me.

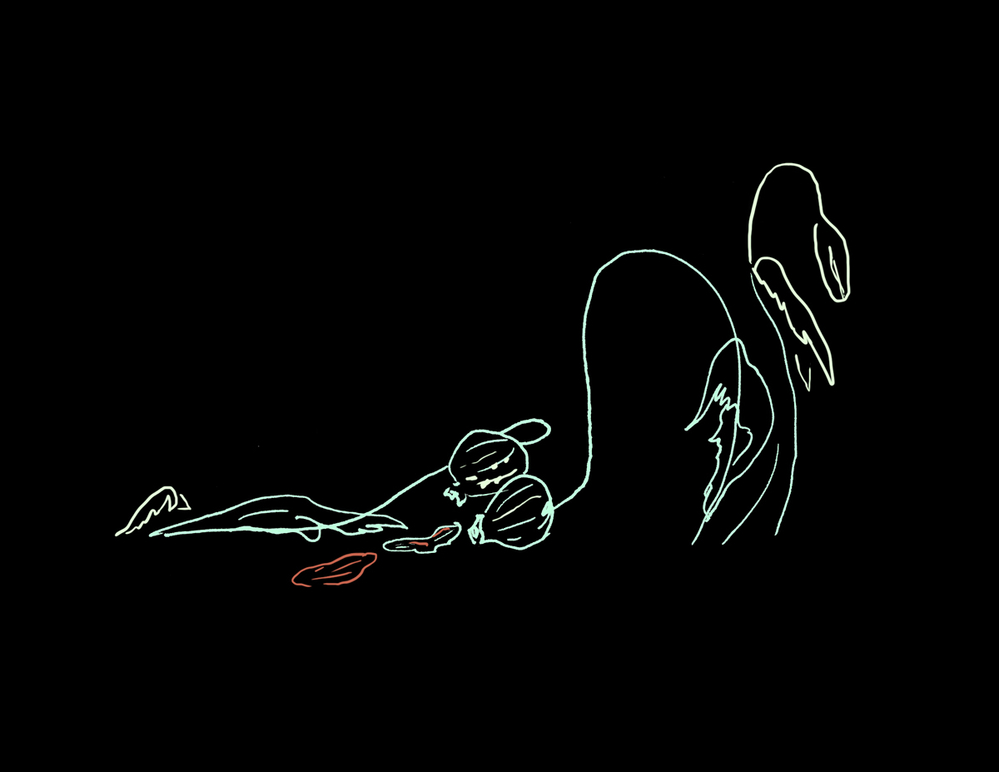

Surveys show that as many as 90% of injecting drug users have witnessed an overdose. (Mari Kanstad-Johnsen)

In the fight against overdoses, Walley and Bigg have pitted naloxone against opioids – one type of syringe against another – for more than 15 years. By 2010, more than 3,500 overdoses had been reversed in Massachusetts alone. Nationwide, the figure was 10,000. These numbers are almost certainly now much larger given the rapid expansion of naloxone use.

Walley’s programme is now being used as a model across the US and around the world. In April of this year, the Food and Drug Administration approved Evzio, an automated handheld injector that carries a single dose of naloxone. The manufacturers designed it for people with no medical training, and hope that the device will make people more likely to carry and use naloxone. Rhode Island and at least three other states have made naloxone available without a prescription. Walgreens, a major US pharmacy chain, has begun to regularly stock the drug.

The overdose epidemic hasn’t abated: drug overdoses are the leading cause of accidental death in the US, claiming over a hundred lives a day and killing more people than car accidents. Nor has opposition to naloxone programmes completely disappeared. But the programme’s success has left critics with little ground to stand on. In a battle with few victories, putting naloxone in the hands of drugs users is one of the few strategies to have proved successful.

This summer, I paid a visit to Walley at his office in Boston. He was dressed in a crisp white shirt, navy slacks and an orange bow tie, and was working at a standing desk. He told me he had dealt with a string of patient emergencies that day, the first at 5am.

Despite its success, his programme retains its pilot status. Walley would like naloxone kits to become a standard part of the health system, for instance; right now they’re still distributed via places like AHOPE. Getting private health insurance to pick up the tab for naloxone is difficult, although he says progress is being made. And more drug users need to be channeled into primary care, which in itself is a challenge.

In Walley’s practice at least, integration is well on its way. “Do you have naloxone?” he asks his patients. “Do you know how to use it?” Now they often say yes. They’ve used naloxone on their friends, and have had their own overdoses reversed by the drug. Many tell him they would be dead without it.

It was a sweltering July day when I visited Walley. I walked back to my hotel afterwards, and headed down the hallway to get some ice. I was looking forward to a cold soda as I organised my notes and packed my suitcase. Then the flashing lights caught my attention. I walked over to the third-floor window and saw an elderly man on the sidewalk below me. He was wearing a Boston Red Sox baseball cap and lay motionless under a lamp-post. A medic gently slapped the man’s face to see if he would respond. He didn’t.

Then the medic pulled a small tube from the ambulance. I spotted a yellow nozzle on the end of the tube, and realised it was the same nasal naloxone spray I had seen over and over again during my week in Boston. The medic bent down and squirted it up the man’s nose. At first, nothing. I held my breath. Then the man moved. He moved slowly at first, but eventually he teetered to his feet and the medic helped him into the ambulance. In less than three minutes, the man had come back to life.

This article first appeared on Mosaic and is republished here under a Creative Commons licence.

This article first appeared on Mosaic and is republished here under a Creative Commons licence.