The economy is affected by fuel price increases at all levels

COMMENT

The rising price of fuel has entered uncharted territory, with serious economic ramifications for consumers, businesses and the economy.

It is thus paramount to fully appreciate what the main drivers of this spike are and what corrective measures can be taken. The fuel price, which is adjusted monthly based on import price parity, has a significant effect on consumers and businesses, and ultimately on the demand for all goods and services in the economy. Fuel price hikes also contribute to inflation.

The economy is affected by fuel price increases at all levels. In the macro-economy, it leads to a decelerating gross domestic product and a worsening of the country’s balance of payments. At the meso-economic level, industries highly dependent on fuel, such as commercial agriculture, face increasing input costs. The food value chains, including production, processing and transportation, are affected, which means the prices of related goods and services are directly or indirectly affected. At the micro level, many poor households are heavily dependent on paraffin, which means fuel increases directly raise their cost of living.

The fuel pump price in South Africa comprises various components, including both international and domestic elements, but the basic fuel price (BFP) is primarily determined by international oil prices and the exchange rate.

READ MORE: ANC: Increase petrol reserves and freeze fuel hikes

The price of crude oil plummeted by 169% between 2012 and 2016, from an annual average of $109.45 a barrel to $40.68. Such a sharp decrease in the price of oil would be expected to translate into a similar decrease in the price of fuel. But this was not the case. Instead, the price of a litre of fuel inland (95 unleaded octane) increased by 8%, from an annual average of R11.56 in 2012 to R12.63 in 2016.

Over the same period, the rand depreciated by 44%, from trading at an annual average of R8.21 against the dollar in 2012 to R14.71 in 2016. This could in part explain the increase in the price of fuel, although the relative stickiness of the price of fuel in the face of a huge drop in the oil price warrants further explanation.

What is perhaps more surprising is that, when the rand appreciated by 22%, at an annual average of R14.71 against the dollar in 2016 to R12.10 in the first five months of 2018, the price of a litre of fuel inland (95 unleaded octane) increased by 13%, from an annual average R12.63 in 2012 to R14.59 in the first half of 2018.

If the depreciation of the rand was indeed responsible for increasing the price of fuel in the preceding period, its appreciation by a larger margin should have at least translated into a decrease in the price of fuel.

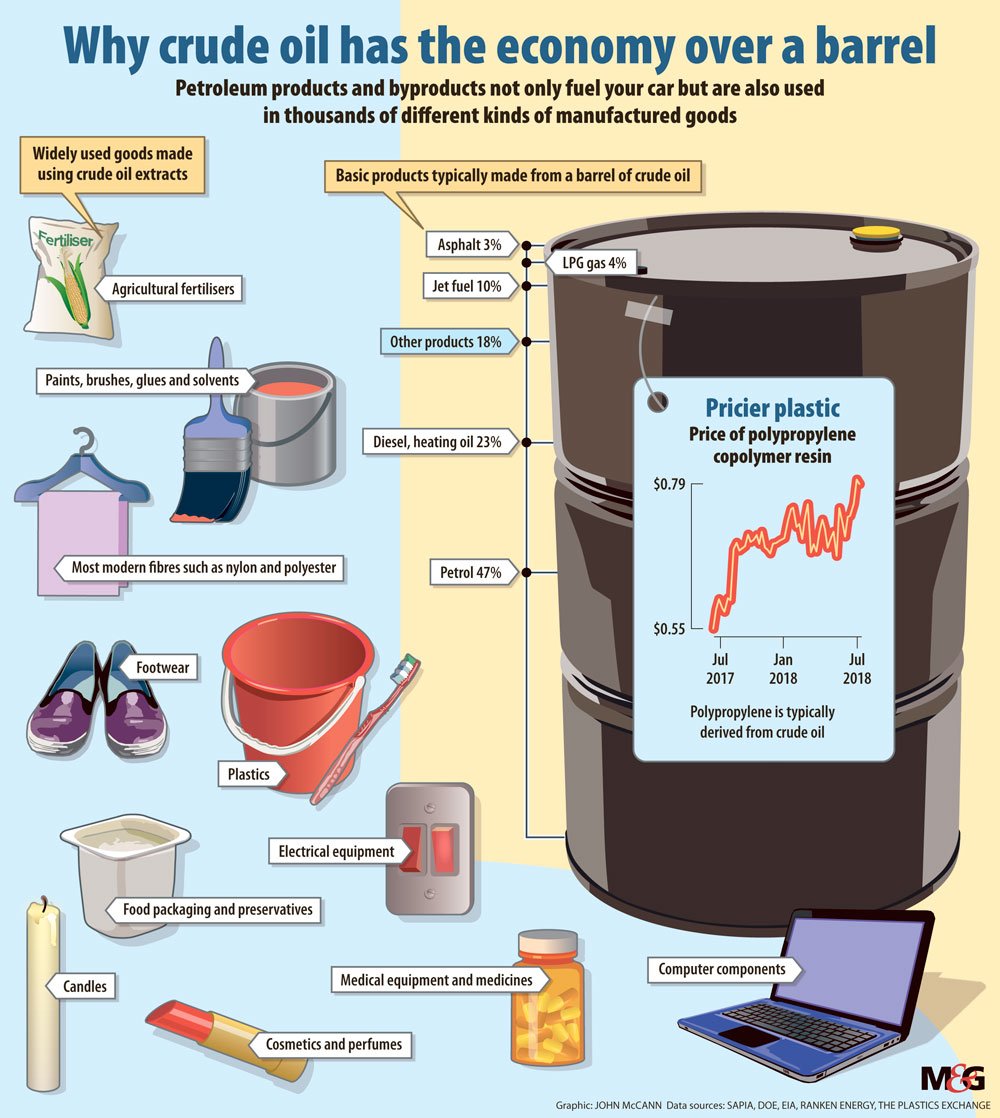

The recovery of the price of crude oil by 38% must be factored in, from an annual average of $40.68 a barrel in 2012 to $65.63 a barrel in the first half of 2018. But the continued increase in the price of fuel cannot be solely attributed to the increasing international oil price. This then raises the question: What other factors are influential in the price of fuel?

The other vital constituent of the BFP is the price of importing oil. This has various components, which include freight, insurance, landing, wharfage, coastal storage and financing of coastal storage. Ascertaining an accurate figure for this is complicated but it is difficult to imagine that it is largely responsible for increasing the price of fuel. In any case, according to the department of energy, the BFP constitutes about 43% of the fuel price. The far larger portion is attributable to domestic features determined by the government. They include tax, an equalisation fund levy, a customs and excise levy, the Road Accident Fund (RAF) and the Slate levy, which is to finance the cumulative under-recovery by the industry.

Some domestic features beyond the government’s control are transport costs, wholesale margins, retail margins and service costs.

The two main levies under government control are the general fuel levy and the RAF levy. The general fuel levy is a tax on every litre of fuel sold. It increased by 22% from R2.55 in 2016 to R3.37 a litre in 2018, reflecting an average annual growth of 9%. The RAF levy, which is to compensate victims of road accidents, has risen by 20% from R1.54 a litre in 2017 to R1.93 a litre in 2018, an average annual growth of 11%. For a litre of fuel inland (95 unleaded octane) that currently costs R15.79, R5.37 (34%) goes to the fuel tax.

READ MORE: Petrol, toll fees to add to consumer debt burden

This means a decrease in other associated costs has a limited effect on reducing the fuel price.

The high taxes on fuel could also explain why fuel prices are higher in South Africa than in its regional neighbours. As of May 2018, the price of fuel was lower in Namibia (R11.60), Botswana (R10.49), Swaziland (R12.72), Lesotho (R11.10) and Mozambique (R13.35) than in South Africa inland (R14.97).

Some consolation for South Africans is that prices in advanced economies are much higher. In May 2018, the price of fuel was steeper in Iceland (R26.57), China (R26.07), Norway (R25.07), Monaco (R24.58), the Netherlands (R24.20), Denmark (R23.32) and Portugal (R22.07). The exception was the United States, where it was R10.21.

Because oil prices in international market are the same for everyone, the major differences are mainly attributable to different tax regimes.

South Africa is a small open economy and the volatility of the exchange rate has a significant effect on the fuel price. Therefore sound macroeconomic fundamentals and structural reforms, such as a mechanism to smooth the fuel price, that would cushion the effects of an adverse exchange rate are crucial.

The increases in the general fuel levy and the RAF levy should be aligned to inflation and structured in such a way that they will protect the poor from the adverse effects of high fuel prices. The refining capabilities of energy and chemical company Sasol could be enhanced and its output could be mixed with imported crude at all the refineries and the resultant cheap oil could then be used to stabilise and subsidise the price of fuel.

Given that African oil production far exceeds refinery output, South Africa must also work together with other African countries to increase African refining capacity to bring down the price of importing oil to the continent.

Thando Ngozo and Sabelo Mtantato are senior researchers at the Financial and Fiscal Commission. These are their own views