No go: Energy Minister Jeff Radebe has rejected a potentially dodgy deal involving a former Jacob Zuma benefactor. (Madelene Cronjé)

Energy Minister Jeff Radebe has scuppered state energy company PetroSA from signing up for an ambitious and risky R22-billion commitment to Nigerian oilfields owned by controversial Jacob Zuma Foundation benefactor Kase Lawal.

In June, Radebe rejected the company’s budget and five-year corporate plan, which contained ambitious plans to increase the refining of Nigeria Oyo crude oil to produce petrol and diesel, saying it was not detailed enough and used incorrect assumptions.

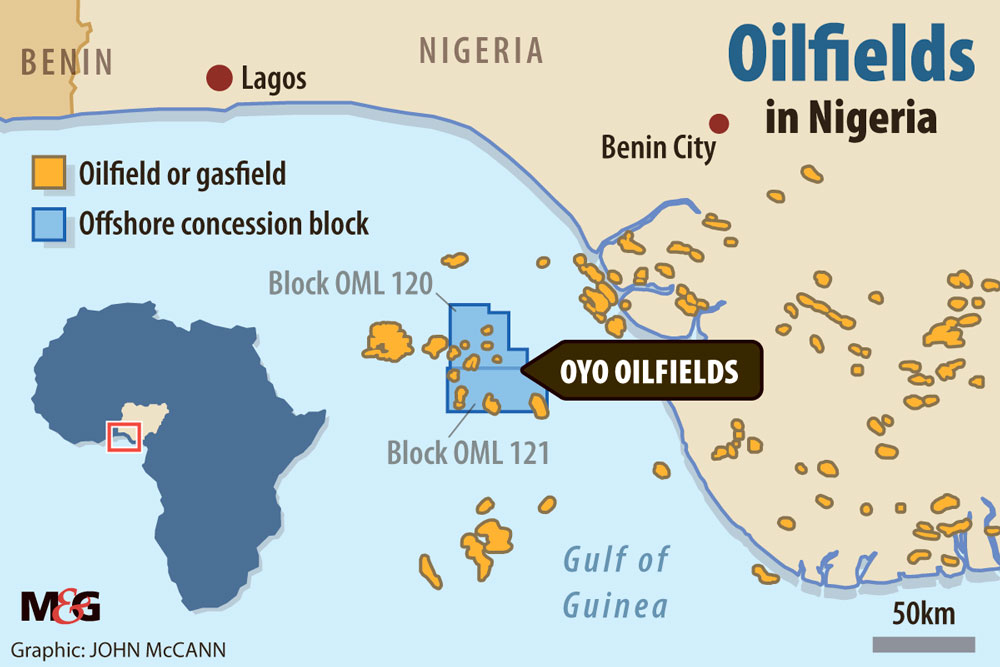

The commitment to procure 23-million barrels of the oil, at a cost of R22-billion, over the next five years underpinned the strategy that would take PetroSA further away from its previous investment in gas-to-liquid technology.

Radebe’s move, made in a letter that exposes rifts between him and the Central Energy Fund (CEF) Group, has left executives and the board at PetroSA scrambling for an alternative corporate plan five months into the new financial year.

PetroSA is overseen by a board that — alongside the state’s other energy assets, including the Strategic Fuel Fund — reports to the CEF. The CEF is wholly owned by the state through its shareholder, the department of energy.

A senior CEF insider said the rejected corporate plan and budget for 2018–2019 was the latest signal in Radebe’s intention to scrap the fund’s leadership, pointing as well to a recent advertisement for nominations and applications for a new board of directors for the CEF and all its subsidiaries.

The controversy behind Lawal

Lawal is a headline-grabber whose deals include a Public Investment Corporation (PIC) investment in the dual listed (JSE and Wall Street) Erin Energy, which earlier this year filed for bankruptcy after Nigerian authorities stopped the company from exporting oil because of a dispute over its licence to sell oil.

The move by the Nigerians meant the PIC’s 2013 investment — part of which was used by Erin founder Lawal to purchase the “economic rights” to oil mining licences from companies owned by him and his family — could be wiped out.

Investigative journalism unit amaBhungane earlier this year described the PIC’s investment in Erin, which at the time was on the verge of bankruptcy, as “dodgy”. Journalists reported that it was one of the reasons for a falling out between the PIC’s then chief executive Elias Masilela and then chief investment officer Dan Matjila that ultimately led to Masilela’s resignation.

What the PIC missed at the time of concluding the deal was that Erin was buying the economic rights to the licence and not the licence itself — something Erin revealed after the deal had been made — and also that Lawal was in dispute with the licence’s original owners, ENI Oil, over full payment for the licence.

The fight inside PetroSA

Last Friday, more than a month after Radebe’s deadline for a new plan by June 30, PetroSA executives attended an urgent CEF Group special board meeting at the Southern Sun hotel in Morningside, Johannesburg, to discuss the plan.

CEF chairperson Luvo Makasi said they had become aware of the rejection only in the past two weeks because the department sat on the Radebe letter, which was signed on June 10.

He referred all other questions to PetroSA, which failed to respond at the time of going to print.

Radebe’s concerns with the plan, which he described as “requiring further scrutiny and lacking sufficient detail”, include:

- An assumption that Eskom will spend about R600‑million to convert its 150‑megawatt diesel open-cycle gas turbines at the Gourikwa power plant in the Western Cape to combined-cycle gas turbines, to consume tailgas residue from PetroSA’s gas-to-liquid refinery process;

- Increased projections of financial losses for the 2018/1019 year and subsequent years;

- A lack of solutions to the problem of depleting gas feedstock;

- Rapidly deteriorating cash reserves at PetroSA, which account for 80% of the CEF’s revenue;

- PetroSA’s lack of a permanent board and its poor safety record; and

- A “drastic increase” in newly created positions at PetroSA, and an increase in salaries and wages while PetroSA is conducting a strategy review.

Several sources in government, the CEF and PetroSA said the main bone of contention, which has also led to an impasse between PetroSA’s board and its executive, is differences in opinion about whether the company ought to continue with its gas-to-liquid programme or intensify its current strategy of refining light crude oil through its state-of-the-art plant in Mossel Bay.

The plant, the third largest in the world, has been underutilised since the failure of the Ikhwezi project, from which PetroSA recorded a nearly R15‑billion loss at the end of the 2015 financial year. Ikhwezi was supposed to yield 242-billion cubic feet of gas from five offshore wells, but ended up yielding about nine times less, leaving PetroSA with no access to natural gas.

According to the corporate plan, PetroSA will report a R687‑million loss for the financial year that ended in March. Further losses are projected for three of the next five financial years: a R670‑million loss for 2018–2019, R633‑million for 2020–2021, and

R1‑billion for 2021–2022.

The company projected profits of R279‑million and R900‑million for the 2019–2020 and 2022–2023 financial years, respectively.

PetroSA has been a pioneer in gas-to-liquids technology. Those in favour of the company continuing with gas to liquid say the real reason behind the push for more oil, which will require significant investment and will accelerate the plant’s wear and tear, is said to be driven by personal interests.

The proponents of oil, which have the backing of PetroSA’s management and the CEF, argue that, although gas is the long-term vision, the refining of light crude is necessary to keep the company operational.

But questions remain over why the company, in its bid to increase production to 46 000 barrels a day, would place itself at risk by committing to such a large consignment from one supplier.

“Right now they are scuttling around, looking for an alternative crude,” said a senior insider. “[If] they tell you when you ask them that they have sorted it out, they are are lying. They are still looking.”

The insider said the decision on Oyo, which has placed the company’s plans in jeopardy, was taken outside the normal processes and made despite internal warnings from buyers against the company placing all its bets on one oil block.

“Internal objections by the trading manager were shot down,” the source said.

PetroSA did not respond to detailed questions sent to it on Monday.

In his letter Radebe said: “It would therefore simply be an academic exercise for me to approve the document submitted in its current form, as the CEF has, by its own admission, indicated that the contents of the document will be comprehensively altered during the course of the year.”

Radebe’s office did not respond to requests for comment.

Lawal was, among others, exposed in the Mail & Guardian for having appropriated discount Nigerian crude meant to benefit South Africa. He denied wrongdoing. In 2010, Lawal began donating millions to former president Jacob Zuma’s education trust, and he accompanied Zuma in 2011 to receive an honorary doctorate from his alma mater, the Texas Southern University.