Chinas state construction company is helping Algeria build its Great Mosque in Algiers. This is just one of many of Chinas projects on the African continent. (Ramzi Boudina/Reuters)

Forty-eight African heads of state gathered in Beijing on September 3 and 4 for the seventh Forum for China-Africa Co-operation (Focac), a three-yearly display of China and Africa’s “friendship”, “win-win co-operation”and one-directional fund-funnelling.

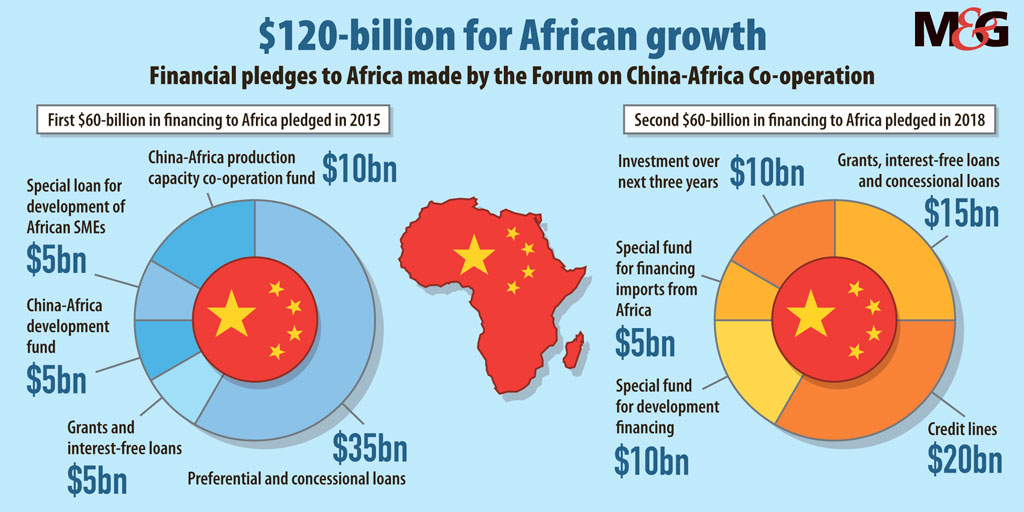

The last Focac in 2015, held in Johannesburg, saw China pledge $60-billion to Africa in the form of loans, export credits and grants.

Focac is ostensibly about improving economic ties and helping Africa fulfil its development potential. This year, Chinese President Xi Jinping spared no sentimentality in his references to China’s “brother” —Africa.

Focac also aims to improve China’s access to foreign markets and resources, while boosting the country’s influence abroad. The forum was the ideal opportunity for Xi to tout his pet project, the Belt and Road Initiative, an ambitious network of trade routes compared to a new Silk Road, from which every country in China’s favour is invited to reap the benefits.

The meeting created a number of photo opportunities for Xi to pose with his African counterparts. He and President Cyril Ramaphosa co-chaired the summit, although there was never any doubt about which leader had the audience in the palm of his hand.

Trade deals were signed and bilateral meetings took place on the sidelines. But Focac boils down to the moment when China announces how much money it is going to funnel into the continent. The whole production is a drum roll for the naming of that magic number as Africa’s leaders wait with bated breath.

The $60-billion pledged in 2015 was a crowd-pleaser, tripling the previous pledge of $20-billion at Focac 2012. Despite major concerns about Africa’s growing debt burden and certain nations’ ability to repay Chinese loans — calling their sovereignty into question — lowering the amount pledged this year wouldn’t have been much of a show of friendship, China must have decided. Beijing stuck with lucky number $60-billion and Xi received a standing ovation after making the announcement.

“Of the $60-billion pledged, $10-billion is labelled ‘investments in the next three years’, which means that Chinese companies — not the Chinese government — are likely to fulfil those investments,” explained Lina Benabdallah, assistant professor of politics and international affairs at Wake Forest University, a private university in North Carolina, United States.

The remainder of the $60-billion comprises $15-billion in “grants, interest-free loans and concessional loans”, $20-billion in “credit lines”, $10-billion for a “special fund for development financing” and $5-billion for a “special fund for financing imports from Africa”, Xi announced.

The amount pledged didn’t come as a surprise. “It is true that in the past, Focac pledges increased each time, while this time the overall figure stayed at $60-billion,” said Benabdallah. “Especially in light of many doubts and questions about the sustainability of Chinese loans and finances with African states, this was to be expected.”

Senior researcher at the South African Institute of International Affairs, Cobus van Staden, agreed: “We didn’t expect the amount pledged to jump as much as it has in the past. This is also a rougher trade environment globally than it was in 2015.”

Although the newly pledged $60-billion takes centre stage, the extent to which the $60-billion pledged in 2015 has been allocated is not entirely known.Xi promises that it has “either been delivered or arranged”.

Ministers of international relations and trade throughout the continent were supposedly “unanimous” in their assessment that the pledges had been or were being fulfilled.

“We applaud China for keeping to its promises,”Ramaphosa told local media. “The industrial plan has resulted in industrial development, the agricultural modernisation plan in greater productivity, and the infrastructure plan has boosted connectivity and integration on the continent.”

The fact is, China has not released statistics on the status of the many millions of dollars’ worth of grants, loans and investment that were announced at Focac 2015. The 2018 figure may include projects that have already been initiated, which critics refer to as “double-dipping”. It might not all be new capital.

“Large figures like $60-billion require cautious analysis,” The Washington Post reported after Focac 2015.

“Tracking these projects is actually one of the biggest issues in the whole Sino-Africa field of study,” said Van Staden. “You don’t necessarily get any reporting when projects fall flat or are stopped halfway through, or even when they are completed. Deborah Brautigam’s work at the China Africa Research Initiative [Cari] at Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies [Sais] is very important because it doesn’t only track announcements. Sais Cari also does on-the-ground searches to see how many projects have been completed. They tend to be in quite a unique position in relation to having hard data.”

But Sais Cari’s data has limits, too. A briefing paper produced ahead of this year’s Focac notes that the Cari loans database tracks Chinese loans “through 2017” and shows that Chinese loan commitments to Africa have increased significantly since Focac 2015, with more than $30-billion “committed” by China in 2016.

There is, however, an enormous caveat: “Our loan figures should not be viewed as evidence of China fulfilling Focac pledges,” said Sais Cari. “China’s Export-Import Bank, a government policy bank, is usually in charge of Focac pledges of loans, export credits and credit lines, but a number of other Chinese banks, including China Development Bank, are now making ‘commercial’ loans in Africa. Commercial loans like these have not been part of Focac pledges.”

The briefing paper also warns that huge commercial loans totalling $19-billion that were disbursed to Angola between 2015 and 2016 have necessarily distorted the 2016 figure.

According to Van Staden, there are essentially only three reliable sources for tracking Focac pledges: “One is Sais Cari, the other is Aid Data at the College of William & Mary in the US, and then there’s the Chinese ministry of finance or ministry of commerce — although they tend to be better for large-scale numbers rather than project-specific information.”

China’s funding of Kenya’s standard gauge railway — a 480km line between Nairobi and Mombasa, which cuts travelling time between Kenya’s two largest cities in half — has been hailed as an example of fruitful China-Africa collaboration. Chinese state media says it resulted in the creation of about 4 600 jobs, and related skills-transfer programmes in Kenya will be facilitated by China for up to a decade.

This particular infrastructure project’s funding has, notably, been categorised as both a Focac and a Belt and Road Initiative programme.

The railway has also added significantly to Kenya’s debt burden. According to a report compiled by the China Africa Project and the Africa-China Reporting Project, China holds 72% of Kenya’s bilateral debt, and is therefore its biggest creditor.

In Djibouti, where construction of China’s first overseas naval base outside the country was completed last year, Chinese financiers held about 77% of national debt by the end of 2016, according to Sais Cari data. When Djibouti’s debt jumped from 50% of gross domestic product in 2014 to 85% in 2016, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) expressed deep concern.

There is no shortage of Western critics accusing China of laying a debt trap. In the propaganda frenzy following Focac, Chinese state media declared: “For those who accuse China of ‘neocolonialism’, ‘plundering resources’ and creating a ‘debt trap’ in Africa, the Beijing summit has proven them wrong.”

Ramaphosa maintained a pro-China attitude at the forum by refuting allegations of any neocolonialism on China’s part, calling China a“partner” that stimulates African social and economic development.

While “capacity building” and “peace and security” were two of the items that Xi highlighted this year, the fact that natural resources from countries at high risk of debt distress — such as Angola, South Sudan and the Democratic Republic of Congo — have fuelled China’s rise to the world’s second-largest economy cannot be ignored.

According to Sais Cari, “in Congo the debt situation is so unclear even to the IMF that the president visited Beijing in July 2018 to ascertain just what they owed”.Yet, based on data from 17 African countries, Sais Cari concluded that overall, Chinese loans are not a major contributor to debt distress in Africa.

“I tend to be quite critical of the [debt-trap] narrative,” said Van Staden. “It tends to overstate the portion of debt that African countries owe to China while leaving out how much debt countries in Africa still have to Western institutions. The role of Western countries in adding to the debt burden or having development finance redirected to debt repayments doesn’t tend to get highlighted in this narrative.”

It also tends to gloss over the options that are open to African countries, he said.

“There is an assumption that African countries have an equal chance to get money from [traditional lenders such as] the World Bank, which isn’t the case. This narrative tends to diminish the agency and decision-making of African countries, [implying that they are] childlike and easily seduced by China.”

The continent’s leaders sent out a clear signal at this week’s forum that they are fully capable of deciding what is in their best interest. Likewise, Beijing has insisted that it is not playing a political game. But the dynamics of another generous pledge without publicly defined checks and balances paints a rather dicey picture for Africa’s geopolitical and economic future.