Provocative: Boity is the latest talent to hop onto the bandwagon of creating trap music. Photos: Instagram

A title sets the tone. And Boity did well to call her first single Wuz Dat? because it’s another fine opportunity to ask: What is that? She slips into what Nasty C calls a rap accent, powering through a familiar beat in a familiar cadence. Calling it copy and paste would be fair.

[Boity Thulo collaborated with Nasty C on her first trap single, Wuz Dat? (Photo: Instagram)]

What Boity did was make a trap song, the way we know trap music today. Its presence is felt all over the world and it makes sense, especially in South Africa.

Unlike most genres, hip-hop/ rap was pushed forward by a do-it-yourself culture with enthusiasts drawing from many sources. The ideas spread from their inception in the boroughs of New York. This bricolage of creation inspired musicians worldwide to adopt the wonderful gift from the diaspora. We’re bound to be drawn to the innovation happening among American musicians. They dominate the canon and trap was bound to have an effect on rap music.

Trap makes people move; that’s the intention. It encourages you to feel as involved as the performer, gathering energy from the refrains and one-liners as the back-and-forth motion of the production keeps close to a stiff, sometimes layered,but not laboured, pattern. It’s infectious. We’re very familiar with this formula; there are fragments of it in kwaito and house.

Step outside on any day of the week and you’ll see that we’re no different to others around the world: most of the music we listen to is to have a good time. The lyrics are repetitive, perfect for listening to in crowds. The only defence for the mimicry we see everywhere can be that our artists are chasing that essence, that moment of joy and release for their listeners.

The way producers use 808 hi-hats is the most recognisable feature of trap. Mannie Fresh, an in-house producer at Cash Money during its early years, Shawty Redd and DJ Toomp are pioneers of the idiosyncratic sound. TI was the first to call the combination of drug-tales and rapid-fire hi-hats trap when he worked with DJ Toomp on Trap Muzikin 2003.

The term emerged from the southern states of America to describe a place where drugs were sold or manufactured, sometimes in an abandoned house—hence the reference to bando. The lyrical themes and flows of progenitors such as Three 6 Mafia, Gucci Mane and Young Jeezy, all southern rappers, gave the sub-genre its tropes. They were telling their stories and the stories of their people, a tradition which was carried on by the likes of 2 Chainz and Lil B.

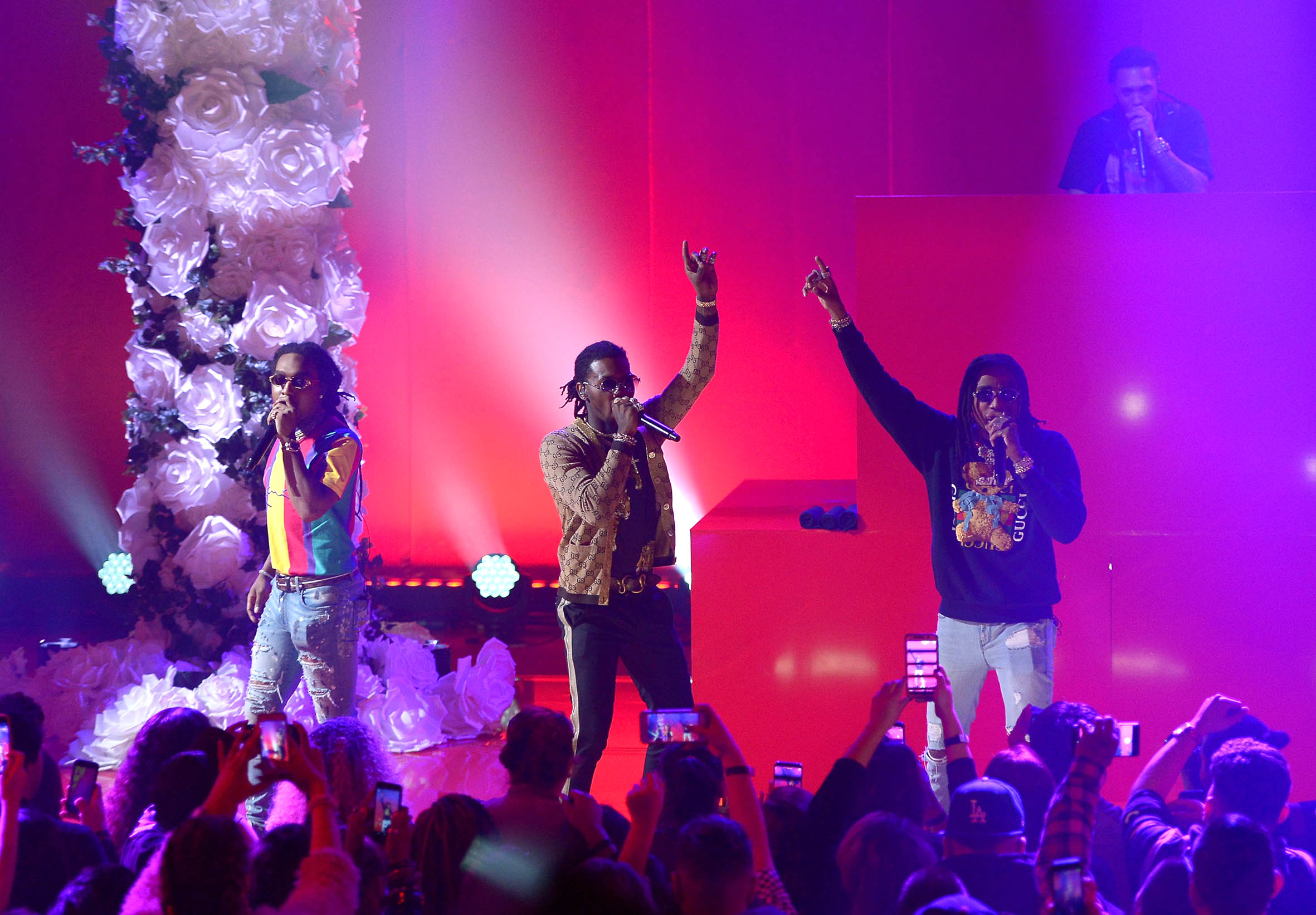

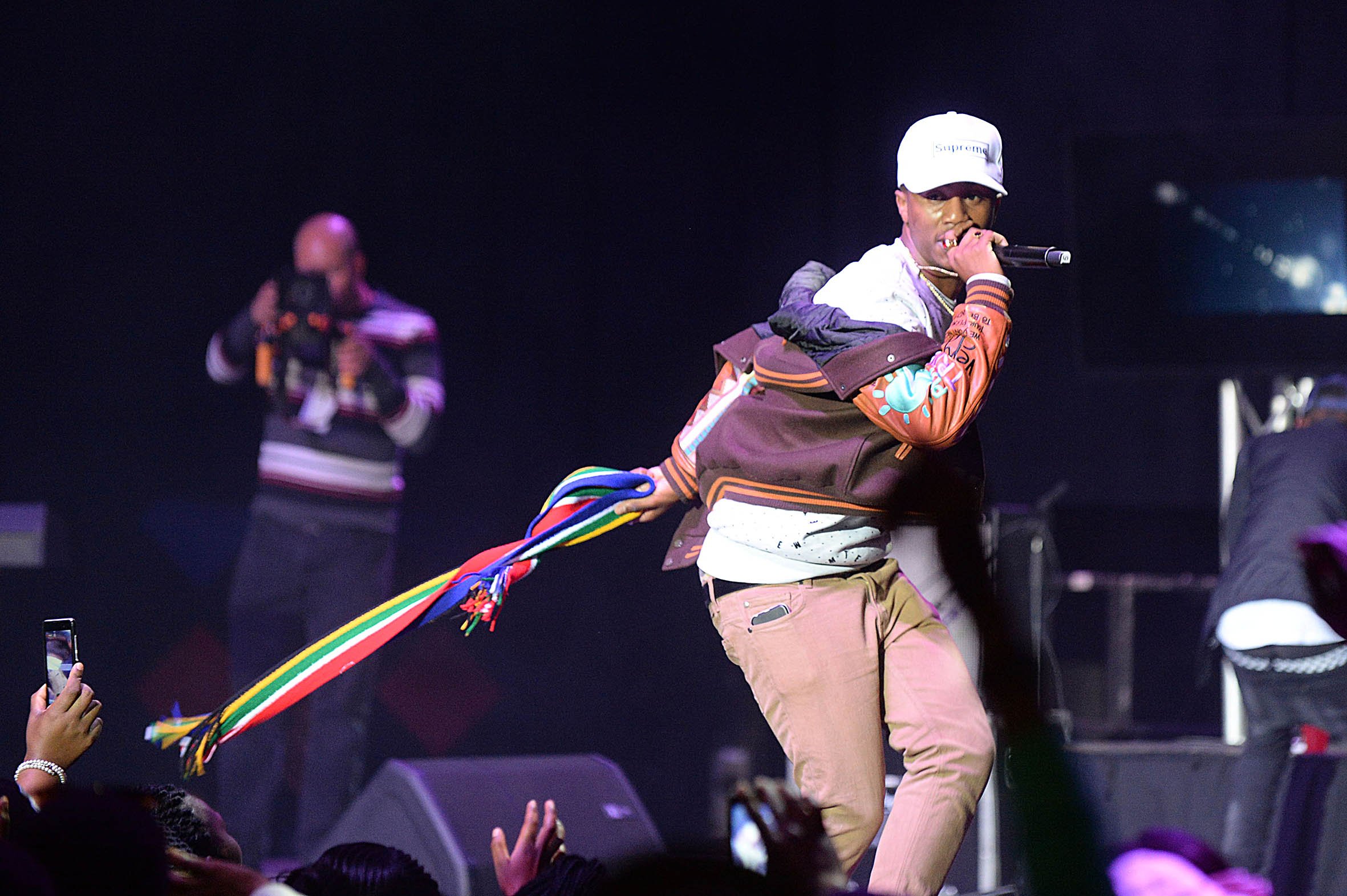

[Trapstars: Gucci Mane (above) is considered one of the pioneers of trap music, having paved the way for many New Age hip-hop acts such as Migos (below). Photos: Angela Weiss/AFP and Charley Gallay/Getty Images]

South Africans may have first-hand experience of struggles similar to their American counterparts, but ultimately, we can only enjoy and interpret without a full understanding of the context from which it originates. Unfortunately too many rappers are lifting flows from Future and Migos, also southern rappers, as well as southern producers Zaytoven, Metro Boomin and DJ Esco. The success of copycats reflects how trap manages to burrow down to our hunger to dance and take on a persona— everyone wants a piece.

The sound gained traction in nightclubs and strip clubs before practitioners began charting. Lex Luger’s influence went further than he may have imagined when he produced Waka Flocka Flame’s Hard in da Paint and Rick Ross’s BMF in 2010, which was a pivotal period in trap’s rise. Pop and electronic dance music learnt lessons from trap and translated it into sounds European that non-rap audiences appreciate. The crossover appeal is exemplified best by Katy Perry’s Dark Horse, which climbed the charts and included a feature from Juicy J, who was a member of Three 6 Mafia. You can now find trap all over the Billboard Hot 100 charts, confirming its status as a form of pop music.

This is why trap makes sense in South Africa. The sound is fun, it’s pop, it’s ubiquitous. Rap has never been as big as it is in the United States, let alone in South Africa. Our rappers have realised that entertainment drives our listeners. If your music isn’t gospel then your audience will lean towards house and, most recently, gqom. If trap is blazing trails in the US then it’s likely that it will have a trickle-down effect here. It’s in the repackaging where the soul seems to be lost, which is to be expected when the end goal is selling a product and not making art that could be considered authentic, while still giving a nod to the muse.

Emtee and Sjava have done brilliantly to interpolate their stories and culture into their renditions of trap, going as far as creating a sub-genre of a sub-genre —African trap. Through their flirting between rapping and singing in their own languages,they’ve given trap a local flavour. Emtee, in particular, keeps to the pillars of trap in his lyrical content, but from his perspective. Sjava plays with flows in a way many of his predecessors in the tradition of trap did,but differs from his local peers in how he uses mbaqanga and maskandi to let his culture shine through.

[The trap music genre has been mastered by South African rappers such as Emtee. Photos: Frennie Shivambu/Gallo Images]

At times it feels as though our musicians believe we haven’t heard of the Americans they’ve used as models. What Emtee and Sjava have done well is to avoid being something they’re not, whereas most haven’t, as is the case with Boity and Nasty C on Wuz Dat?. Where trap in South Africa departs from a similar road to kwaito, house and gqom is how it fails to home in on our own culture.

As the J-Molleys, Frank Casinos, Nadia Nakais and Patrick Lees gain momentum and Cassper Nyovest continues his one-man cover act, it’s clear this is what the people want. What’s that? It’s what gets the people going. The least we can do is learn the history, pay respect to the godfathers and innovate instead of imitating because we won’t stop trapping anytime soon.