Face-off: South Africa argued for patients over profits at the first high-level meeting on tuberculosis. Will it be enough to fight the global scourge? (Reuters)

Graveyard cough, white plague, consumption. A killer by any name, TB has stalked the human race for aeons, lurking in crowded tenements or following miners deep underground, hanging in the air of our hospitals.

Always there, yet rarely spoken.

Today, it kills more people than HIV and malaria combined, the World Health Organisation (WHO) reports. In South Africa, Statistics South Africa’s latest data shows TB remains the leading cause of non-violent deaths.

Yet it took the United Nations 73 years to call a meeting on TB — and only because a very excitable South African health minister agitated enough for it.

On Wednesday heads of state ratified the first UN declaration on the most deadly infectious disease on Earth. In doing so, the world committed to curing 40-million people of TB by 2022. To fulfil their promises, international leaders must also ensure that almost an equal number of people get treatment to prevent them from developing TB.

If the world lives up to its promises, it will save the nearly two-million lives lost to TB each year, according to WHO data. Another 10-million will develop the illness and survive, but with the rise of drug-resistant forms of the bacteria, they may have to forfeit their hearing — or their mental health — to the harsh drugs needed to treat drug-resistant TB.

Watch: Find out what South Africa is doing to find “the missing 30%” when it comes to TB

Older, cheaper treatments for TB that is resistant to the two most commonly used TB drugs, involve at least six months of painful, daily injections. The treatment, which can take years to complete, risks patients’ hearing and psychosis is a side-effect.

Newer, shorter and kinder treatments using drugs such as bedaquiline are available — but at cost. South Africa recently negotiated a price drop for the medicine from pharmaceutical company Johnson & Johnson. The drug, which used to cost middle-income countries such as South Africa R42 000 a course, now costs about R6 000 for a 6-month regimen, international humanitarian organisation Doctors Without Borders (MSF) says in a statement.

But that’s still too high, argues MSF’s HIV and TB advisor Sharonann Lynch.

“Drug-resistant TB is so undertested and treated because of the three C’s: cost, the complexity of treatment and the crappy cure rates. By using bedaquiline rather than the injectable [drugs] we can remove all those barriers”, she explains.

Given this, Lynch says, “the showdown between South Africa and the United States on the declaration ahead of this week’s meeting was almost inevitable”. South Africa saw nearly 333 000 TB cases in 2017, according to the World Health Organisation’s latest report.

“Of course it made sense for South Africa to go to the mat [on the TB declaration] and fight for their and other countries rights to utilise [patent] flexibilities. South Africa should be able to double the number of people on [drug-resistant] TB treatment if they had fair pricing.”

South Africa didn’t just help get TB on the table at the UN. It also took a crucial, hard line during heated negotiations on the declaration’s final wording. The country spearheaded last-minute protests over a 20 July draft statement that failed to incorporate important access to medicine issues.

The bone of contention: Language that would have affirmed countries’ rights to put patients before patents for the public good.

In the wake of the September 11 terrorist attacks in 2001, strange parcels laced with deadly bacteria began to arrive at US office buildings, including those of high-ranking government officials. News reports showed teams in hazmat suits collecting nondescript envelopes from building and quarantining offices.

The tiny bugs inside, once inhaled, could give way to an infection known as anthrax that is almost always fatal, the US research organisation Mayo Clinic explains.

Fearing a chemical weapons attack, the US moved to begin stockpiling antibiotics to treat what could become a mass outbreak. The only trouble was that the patented medicine by pharmaceutical company Bayer was too costly for a widescale response.

So the US threatened to use the World Trade Organisation’s 2001 Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (Trips) to issue a compulsory license for the drug. This kind of arrangement would allow other companies to produce Bayer’s product without a patent because of the public health emergency.

Trips protects countries’ rights to safeguard access to medicine by challenging conventional patent protection on public health grounds.

Faced with the prospect of a compulsory license, Bayer chose to sell the drug to the US government at discounted rates.

Although the US has dabbled in Trips flexibilities itself, trade officials have had a nasty habit of being less welcoming when others do. Given the history, South African officials may not have been surprised when the 20 July version of the TB declaration made no mention of the tools under Trips at countries’ disposal.

It did, however, contain this line: “[We recognise] that intellectual property rights are an important incentive in the development of new health products.”

MSF was quick to point out that the statement is untrue when it comes to epidemics such as TB that are concentrated in developing countries.

South Africa halted deliberations in protest and MSF’s head of its Access Campaign for affordable medicines shot back.

“For almost two months, negotiators have been in heated talks that resulted in a draft declaration that widely diverged from language in previous UN declarations on health and access to medicines,” Els Torreele said.

“This aggressive push by several countries backed by Big Pharma lobbies would severely undercut needed guarantees to protect access to vital tools and medicines for people living with TB.”

South Africa’s objections led to a faceoff with US trade officials. Ultimately, South Africa succeeded in getting a scant mention of Trips into the document but not language explicitly outlining countries’ rights.

In an interview with specialist news service Intellectual Property Watch, MSF advisor Leonardo Palumbo explains the significance:

“The preamble text is meant to be descriptive. But in the text of the document, there is no corresponding operative paragraph or commitment to be agreed upon and acted upon by [UN] member states,” he says.

“This definitely wouldn’t stop states from making use of Trips flexibilities, but the political declaration would not be another tool for countries to do so.”

The tensions around the issue were visible at Wednesday’s meeting as both President Cyril Ramaphosa and US Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar reaffirmed their opposing stances.

“TB is not just a medical condition. Poverty, unemployment, poor nutrition, overcrowding and social stigma…fuel the spread of diseases. This means that the poor and marginalised carry a disproportionate disease burden”, Ramaphosa said.

“We need to ensure drugs are affordable, we must adhere to Trips flexibilities.”

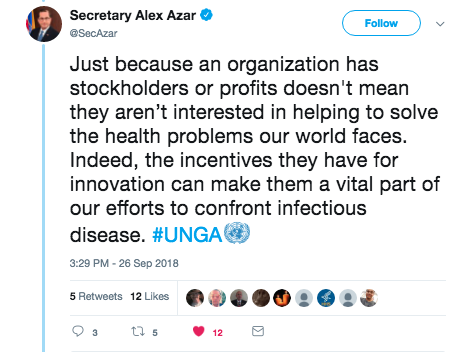

Just hours later, Azar tweeted about the US’ firm commitment to upholding patents:

“Just because an organisation has stockholders or profits doesn’t mean they aren’t interested in helping to solve the health problems our world faces. Indeed, the incentives they have for innovation can make them a vital part of our efforts to confront infectious disease.

The ink is dry on the declaration. Now, activists say the real test will be whether countries put their money and actions behind bringing its words to life. Or whether they return home from New York to the same deadly silence.

But Lynch and others don’t deny it’s a victory South Africa — and others — can claim. “It’s South Africa’s right and those of countries like India to… explore utilising Trips flexibilities rather than waiting again for a drug company to take some benevolent action… and soak up the PR.

“They effectively won.”