To err: Blessing Ngobeni contemplates the power of failure in his exhibition A Note from Error. Photo: Paul Botes

A Note from Error marks Blessing Ngobeni’s second show at Everard Read Gallery — though he has had many more exhibitions elsewhere since bursting on to the art scene in 2012. His work is noted for its politically charged content, but rarely for its aesthetic innovations and development.

I sat down with Ngobeni in a Jo’burg restaurant, one day after his rousing exhibition. His face reflected a sense of both relief and fatigue. After all, A Note from Error is not only a site of restless imagination pouring out of each of its objects, but also a stunningly curated exhibition by Thembinkosi Goniwe, working silently in the background, that positions Ngobeni among the “faces” of contemporary South African art.

As the title suggests, the project contemplates the complexity of erring, from mistakes we make daily to those we’ve been making since the colonial encounters.

Instead of fleeing from the mortifying evidence of our failures, critical art theory has been urging us to see the productive power of errors. Art provides an aesthetic experience through forms that can reorientate our sensibilities. Although sounding slightly like an archaic adage, this introspective maxim on the role of “errors” contains some significant pearls of wisdom to help us to navigate our current socioeconomic minefield.

Ngobeni doesn’t evade or bury errors. Instead, he asks us to sit with, for instance, the fact that “our forefathers were robbed of land with a mirror … something that still affects us, even today, as the youth”.

Rather than giving us a 10-point programme to deal with these errors, in this body of work Ngobeni explores the way art self-reflexively turns to its own image and unravels its own errors.

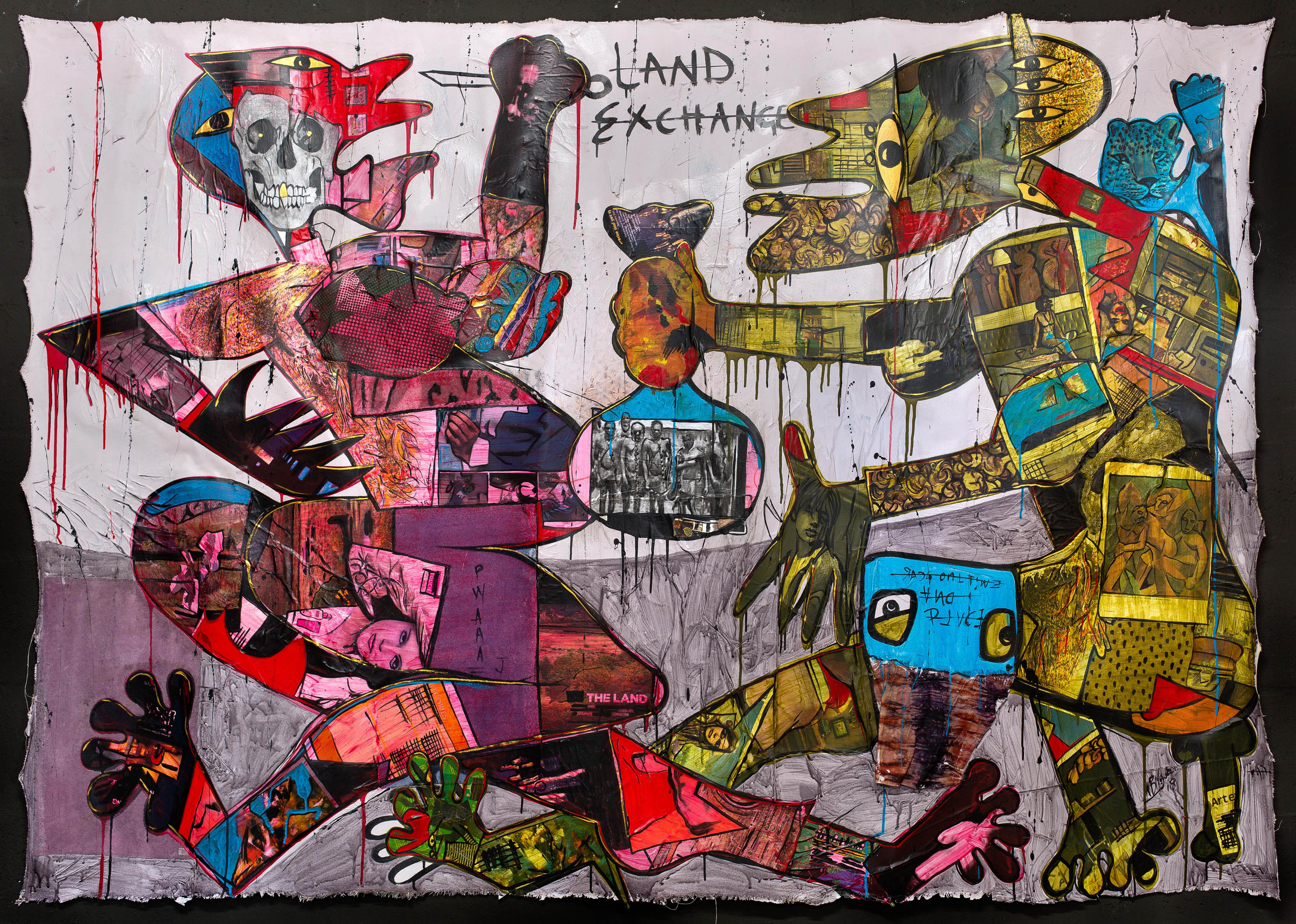

Blessing Ngobeni’s work, which double as drawing-sculptures, reveal his view that beauty cannot be disentangled from the terrible. (Land Exchange by Blessing Ngobeni)

“The error that I see in my work, maybe I can say … I feel like it’s not complete, until now, it’s a sculpture or a performance,” Ngobeni stammers as he tries to explain. “I always study my work. I spend time relooking at my work, trying to find ways of correcting it. So for me, I think in my work I will always see an error,” he laughs, “until I reach that level that now the sculpture is walking, it has engine now.”

Indeed, motion is latent in his work.

One of our greatest mistakes can also be our fear of making errors. From this angle, his works carry an analogy for the social realm.

Ngobeni, now 33, is mostly known for his chromatically decadent and provocative mixed-media paintings, but he has pushed his art to another limit. He’s as prolific as an insomniac, and brings his paintings into dialogue with his videos, installations and sculptures. This ensemble of disparate media establishes a visual synchronicity only attained by such artists as Kemang wa Lehulere, Dineo Seshee Bopape and Athi-Patra Ruga.

Ngobeni says he is sculpturally “skeletonising my work”. This allusion to movement is calculated. Everything always seems to need and, as a result, always ricochets back to painting. “I source out my ideas from the paintings that can be transformed into a sculpture, for example. The paintings are the founders of these ideas.” In the main, “they all carry the same message”.

Ngobeni’s paintings depict loaded figures whose interiors, fixed inside by heavy outlines, are sites filled with what feminist scholar Hortense Spillers might refer to as “hieroglyphics of the flesh”. Be they the paper cut-outs that are referenced, the obscene scenarios repainted with dramatic spectacularity or the textual annotations that leave us conceptual clues, he says: “I skinned the works and now I present the skins.” His wall sculptures, for example, would therefore be the skinless outlines. “I took the skin and left the body,” he wails.

His works are reduced to their bare, linear minimum — doubling as drawing-sculptures. It’s quiet, but not mute. On the other hand, the outlined sketchiness of his standing sculptural pieces retain a boldness preserved only for public art; figures playful and comical, yet serious and quarrelsome.

The centrality of the body, as flesh and bone, is important to him as a reminder of an endless retraumatisation of the black body. From the itinerance of the line work to the caricatural body language of his sculptural figures, we re-encounter the painting’s aesthetic, except now stripped to the bone. For Ngobeni this “skeletonising” of the loaded flesh of his figures isn’t to foster reprieve, but to show that “if the flesh had pain, how much more the bones”.

This suggests a productive restlessness in constant search not only of a rectification of the errors but also of a language to better understand them, and therefore stretch them. One must heed this aesthetic disquiet and gesticulation as enunciative of what Teresa Firmino, during a panel discussion on Ngobeni, recently called a “beautiful nightmare” or Fred Moten, in reference to jazz, calls “a riotous solemnity, a terrible beauty”.

This captures the productive tensions involved in Ngobeni’s work, in which beauty cannot be disentangled from the terrible. Being black is to occupy this uncanny place of repulsion and allure, of oscillating between life and death without a pause.

Movement in Ngobeni’s work happens at multiple levels and in different ways. It is not only in the intermedial dialogue between the works, or even its aspirations for a collaborative exchange between the artist and various cultural practitioners. It is not just in the musically suspensive auras of his still works, but it is also in the animated gestures of his characters doing a jig. For instance, in the video Spooky City (2018), Ngobeni collaborates with a jazz trio comprising Sisonke Xonti, Keenan Ahrends and Thembinkosi Mavimbela, whose musical scores responded to the animation — the bodily movements of his characters are as illegible as they’re beguiling.

Movement also pervades the forms he constructs via his contorted figurines, with comically exaggerated but suspended poses. He believes that, if people can see his works as mediums that “communicate ideas visually” about “things we live with but cannot tell the world about”, these intimate moments will not go unnoticed. “For instance,” he elaborates, “there’s so much body language that has existed among black people since long ago, and [it] shows when they communicate. Within my paintings, the way the characters are presented, you can see there is a lot of movement, even though the characters are flat. So I observe those things and play with them within my work. People don’t like to pay attention to that, but that is how I’d like for people to see my work, rather than being identified as someone who is from a certain background.”

For the things we live with but cannot articulate, their potential to be expressed sometimes lies in these inanimate gestures. But the visual vocabulary of these renditions scarcely gets the same attention. According to Goniwe — on the same panel as Firmino on Ngobeni at Everard Read Gallery — this “limits us in understanding or getting to grips with what Blessing is bringing into the contemporary space, because we identify the artist not only with what they do but [with] how they do it”.

Those That Have Never Been on a Battlefield

Goniwe’s remarks add emphasis to the use of colour and the provocative cues of the titles given as elements worth investigating. Titles such as Ghost Pianist and the Generation of Neglect, Those That Have Never Been on a Battlefield or Whipped Land, instantiate a poetics of naming. Ngobeni’s palette follows this poetry of terrible beauty in its dark over-indulgence, spilling over and yet controlled. It isn’t colour used to hide things unspeakable by glossing over them or glamourising the wound. The dark vitality of Ngobeni’s work invites us to bear witness to a truth born out of trial and error, from colours in triumphant despondence bewailing the crimes made against the flesh.

Whipped Land

A Note from Error is a show that is as exciting as it is thought-provoking, making us ask questions that are hardly posed. Ngobeni isn’t saying these bombastic ideas simply for the sake of our insatiable interest in concepts, but also as someone who, after seeing the difficulty in being an artist, has recently started an art prize that offers young artists studio space, a small material budget and a monthly stipend. Yet artists of his ilk don’t often get the recognition they deserve. I hope institutions that give awards recognise Ngobeni for the creative force that he is.

A Note from Error runs until December 21