(John McCann/M&G)

Almost everyone has a home affairs horror story to tell and the words “we are offline” often feature.

But the agency that runs the department’s network says the managers of the department’s offices could resolve 80% of them. Simply ensuring that there is diesel to run the generator, buying sufficient prepaid electricity or switching on a router could cut down the number of days home affairs offices are offline, according to the chief executive officer of the State Information Technology Agency (Sita), Setumo Mohapi.

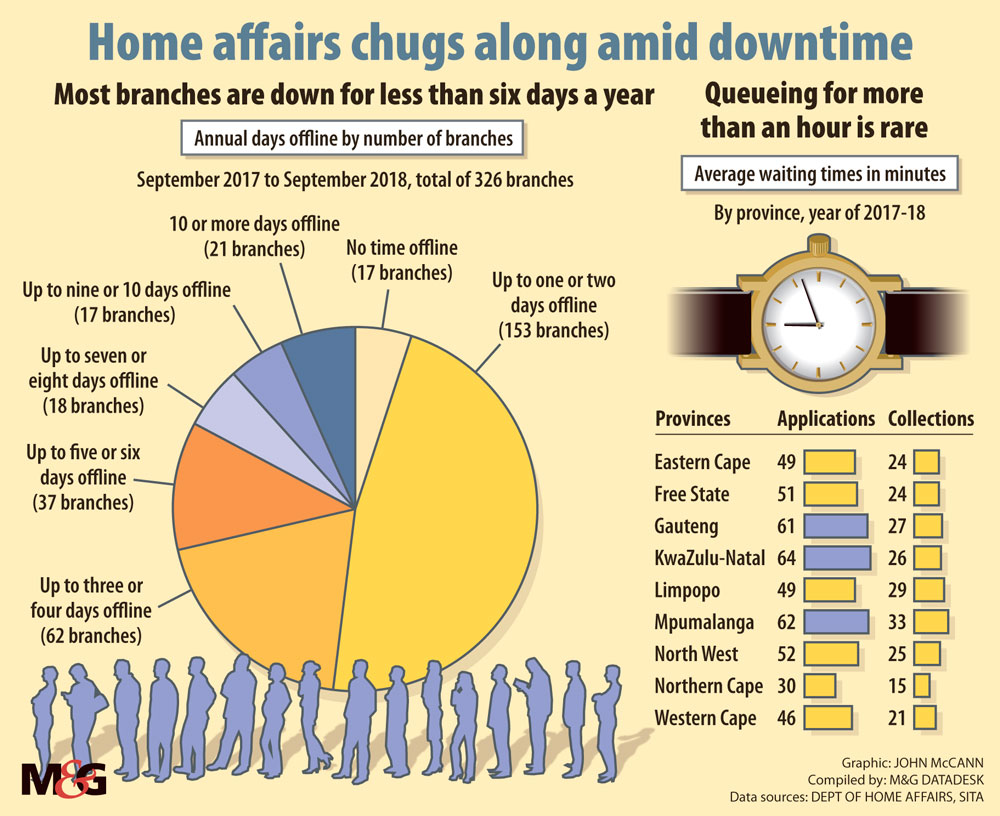

According to the records of 326 home affairs offices, at least 20 were offline for 10 days or more since September last year.

The data shows that Hlabisa in KwaZulu-Natal, where the system was unavailable for 130 days because it uses prepaid electricity, was the worst centre. Hlabisa’s worst month was in August when the centre was only available for 8% of that month, the equivalent of two days.

“When the system is down, I look at my data centre, which is up, my network is up … In the minds of the public servant, the IT system is down. In the minds of the client, it is Sita who is the IT service provider,” says Mohapi.

“But the system is down because the router is out in that centre; and I don’t even have sight of that router. There is supposed to be an IT person who is managing that router and that IT person does not account to Sita.

“The system could also be down because there is no power. Everybody knows that you should have secondary power like a generator. So the power goes off, the generator does not kick in and the system is down. There is not much I can do about it,” he says.

He tells a story about when one centre was offline because the electricity had gone off, even though the generator was operational, it was discovered that no one had put diesel into the tank, which was next to the generator.

The second worst centre is in Dobsonville in Soweto, which was offline for nearly 50 days in the past year. Last week, when the Mail & Guardian visited the centre, it was offline again.

The centre, which is next to a public park and surrounded by tuck shops and vendors, also doubles as the local South Africa Social Security Agency grants office. But, unfortunately for those wanting to get their passports or identity documents, the power was off and the centre was only processing birth certificates on that day.

At the Lenasia home affairs office, the system was unavailable for 18% of the past year.

“In certain cases, the centres are offline due to copper theft. In the Soshanguve area, there is an office that was offline almost every week. We found that people were just stealing the copper. In Soshanguve, we cancelled the line and installed wireless microwave technology,” Mohapi says.

Meanwhile, there are a handful of centres that have not been offline in the past year, including Zeerust in North West, Ladysmith in KwaZulu-Natal and the Marabastad refugee centre in Pretoria.

When the M&G visited the Marabastad centre, it was buzzing outside, where there are informal traders, a mobile police station and randomly parked cars. There was a queue of foreigners waiting to get their papers cleared.

One of the traders, Kisana Mbiaka (35), who’s originally from the Democratic Republic of Congo, says she has been doing business there since 2006. She says things have changed.

“Everything is fine. There are no complaints. Before it was not easy, but right now everything is fine,” she says, adding that she also got her papers there.

Die Hoewes in Centurion is also a better bet if you want your affairs attended to. It has been online for 99.8% of the year.

But there are some inconveniences attached to visiting the centre, which is right next to a Gautrain station. Those who drive there are only likely to get parking on the orange lines across the road. Customers are only allowed into the premises in batches of about 15 people. The rest queue outside along the fence, huddling under the shade that a few trees offer.

Among them was Elise van Straten, with her mother Anlie, waiting to get her passport. “This is the third home affairs we’re at today,” Elise says.

“Two of them couldn’t help us but hopefully this one can. If I say I’m doubtful, I think I have a good reason. The first one was offline. They were online for 45 minutes. I left home at 5.45am, got there at just past 6am, stood in the queue and then at 8.25am they said, ‘Sorry, we’re offline’.”

Another person waiting in the queue says that since the centre was moved to an electronic system, things seem to have speeded up.

“The only issue is sometimes waiting for them to get work done — that takes a long time. Another problem is when they’re offline and they can’t tell us how long they’ll be. We don’t know how long we’re going to wait here. That’s frustrating because you take off from work and then come here not knowing how long you’ll be. But I have had a few good experiences as well. My wife’s passport took three days — that was excellent.”

But even at some of the better centres, such as Maynard Mall in Cape Town, which had not been offline at all between September 2017 and 2018, the gremlins are at work. This week, Leona Binedell says, on her second visit to the centre, it was offline.

“It was an absolute laughing show. When I went in there, they said it was offline. I wondered what the other people were sitting there doing. So no one can get an ID, no one can get a passport even if it’s an emergency. There is no back-up system,” she says.

Before the Jacob Zuma years, Bindell says she had never experienced home affairs centres being offline.

Home affairs spokesperson David Hlabane says the department has noted the network downtime caused by power failures and infrastructure breaks.

“Sita has appointed Dimension Data to assist in the assessment and stabilisation of the networks and, since the inception of the project, there has been tremendous improvement in the network performance,” Hlabane says.

He adds that home affairs’ footprint is inadequate for the 57.7-million citizens who are serviced in 411 offices.

“The post office, for instance, with a clientele way less than that of home affairs, has more than 2 400 outlets. Therefore, for it [the department], waiting-time complaints are a daily occurrence.”