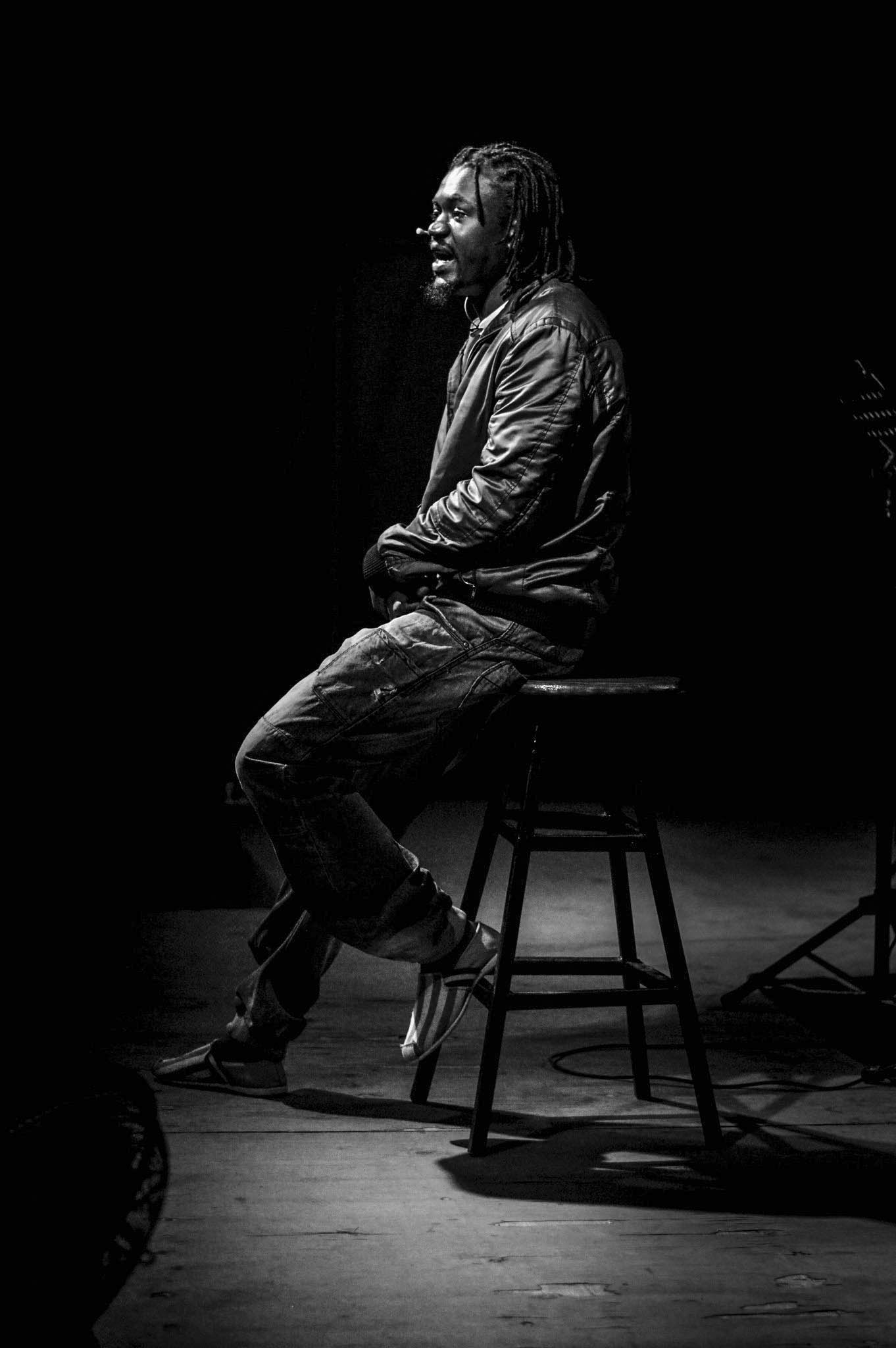

Voboy is one of Kenyas activist poets pushing for

social and political change, draw on the tradition of oral storytelling.

Nakuru — It is a chilly Sunday afternoon at the Agora Centre in Nakuru, Kenya. The stage is lit up as if for a music concert, and there are hundreds of people in the crowd jostling for a clear view. Most are forced to stand.

They are waiting not for a band, but for a poet. His name is Gregory Ochieng, stage name Mbunge Aliyeparara (the broke MP). He is launching his new anthology, The Quest for a King, and, when he finally makes it on to the stage, he does not disappoint. As he speaks, with an easy flow, the crowd snaps their fingers and hiss in accompaniment.

Mbunge Aliyeparara. (Courtesy Upgrade Poetry)

Kenya might be one of the few places in the world where poets are treated like rock stars. Spoken poetry, drawing on a long tradition of oral storytelling, is enormously popular all over the country.

The genre is also becoming increasingly political. Kenyans can sometimes struggle to articulate their problems. For Ochieng, the words come easy.

Kenya is a “state gone rogue”, he tells his crowd. “I fear being sidelined because my tribe is inferior/ Tribalism has overridden reason/ Die for your tribe is a slogan I have lived knowing/ It’s so sad that my tribe is the reason my life is in danger /Leaders donating weapons for charity.”

The words resonate with his audience. They nod along, clearly experiencing the raw emotions that his rhymes evoke.

“I live in a country where my second name betrays me/ That’s why I use AKAs to identify myself.”

Ochieng does not shy away from difficult subjects. He speaks about the massacres of young police recruits in Baragoi and Kapedo, thrust into danger while their bosses were sleeping. He speaks about the unsolved murders of politicians and political activists, including Tom Mboya and Robert Ouko, whose deaths, even decades later, remain a taboo subject.

It’s the hypocrisy that gets him most. “We have cases of an MP who was given a tender to supply street lights and was later charged for stealing them. We have maize scandals by senior government officials yet we have Kenyans dying of starvation. Yet when they die we are forced by the government to mourn them as the flag is flown half-mast and the country is launched into three days of mourning,” he said in an interview with the Mail & Guardian.

Ochieng believes that poetry can bring change. “People take poetry more seriously. They tend to listen more to the message. People have been going to the streets for demonstrations, out of emotion, for a long time, but no action takes place. Results are not achieved, since it ends up mixed with looters and violence. The endgame is that the message does not reach home,” he said.

Ochieng is one of a growing number of activist poets who use their platform to promote the type of changes they want to see in their country.

Poets such as Kevin Maina, aka Voboy, whose fiery verses have earned him a ban from some government departments. He felt compelled to turn to poetry in 2014, after a spate of extrajudicial killings targeting Kenya’s Muslim community.

His poem Times Are Coming references discrimination against this community. “Times are coming when politicians will cause a political divide using religion/ They will instil more fears using that/ We will be scared of person in a buibui than the actual buibui.”

The word buibui has a double meaning, referring both to a type of dress worn by Muslim women and to the Swahili word for spider.

Or poets such as Rachel Stephanie Akinyi, popularly known as Spontaneous, whose family was not convinced by her career choice. One close relative slapped her when he discovered that she had been performing poetry. She persisted, she said, because she knows how powerful her words can be. “Every time I hear them say ‘you have touched a part of my life, you have breathed life into my nostril’, I feel glad I made a change in someone’s life. My poetry is about giving life to people.”

Spontaneous

Akinyi’s poetry tackles taboo subjects such as sexual violence against women and human trafficking. She recites: “I became part of the dignified statistics/ With young lads to entertain and grandaddies to entertain/ Only God knows the many times that tears have been my enemies/ And pillows my frenemies”.

Evans Ndirangu, stage name Evansquez, believes there is room for plenty more poetry — and more activism. “One always wants to hear more. It’s a nice blend of words and the presentation is better than a seminar or open-air meetings. The crowd relates better and actually ends up even repeating the main lines in my poems,” he said. “The words marinate in the minds of the listeners. In reality, poems are now pushing people to demand for civic change. Especially before the elections, I was able to perform in several political functions that were graced by senior politicians. Just by the fact that I could highlight social injustices including extrajudicial killings and high rates of corruption to the crowd, I was able to critique the government and enlighten the public.”

Ochieng, fresh from his electric performance in Nakuru, agrees. “Even if I complain to and about leaders, they won’t change. If I target citizens, especially voters, they can spearhead the change once they go to the ballot,” he said.