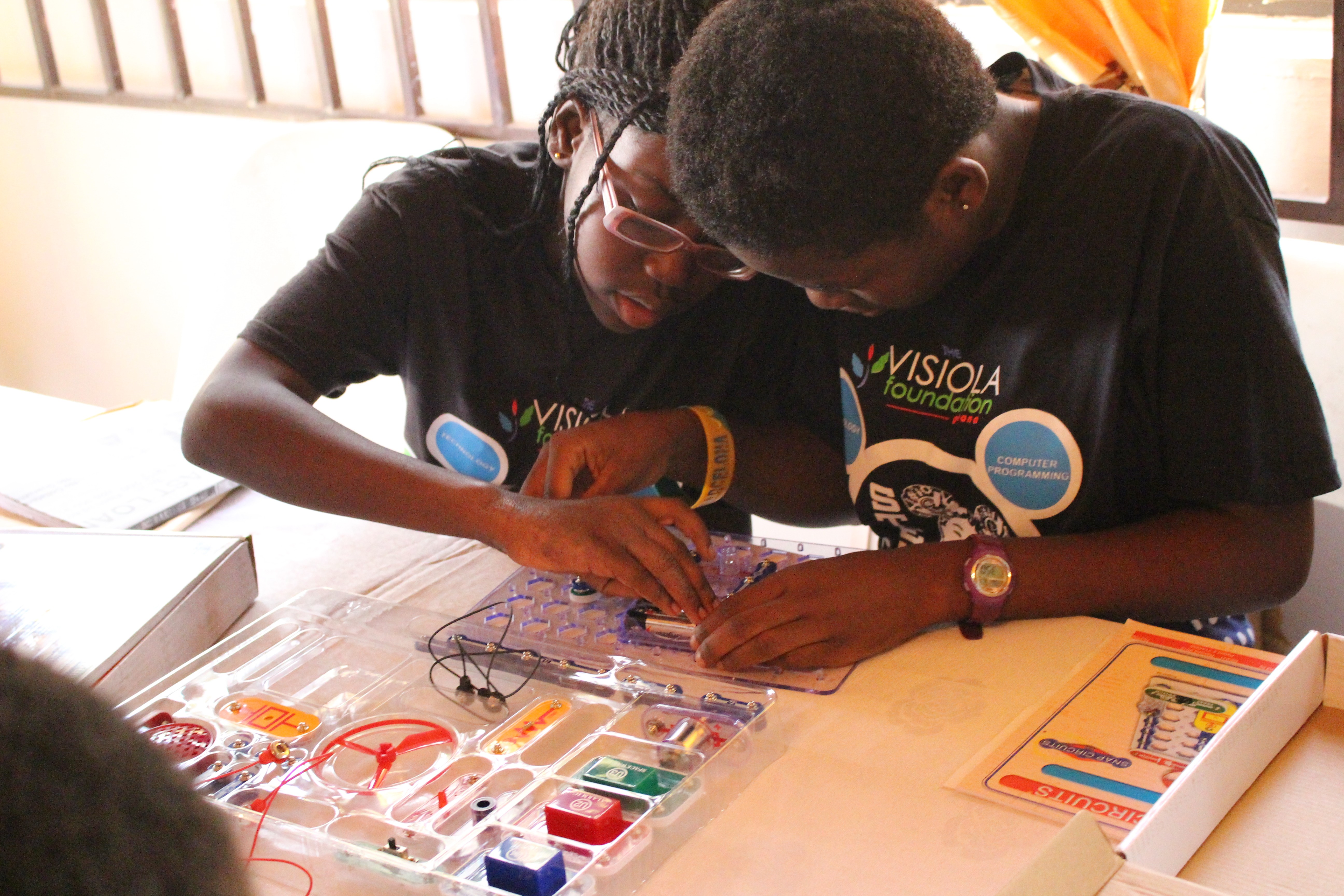

As the summer STEM camp draws to a close for another year at Visiolas headquarters, the glowing reviews from the teenage participants are flooding in. (Photos: Visiola Foundation)

Down a quiet tree-lined street on the periphery of Abuja, one of the fastest growing cities in the world, a classroom brims with activity.

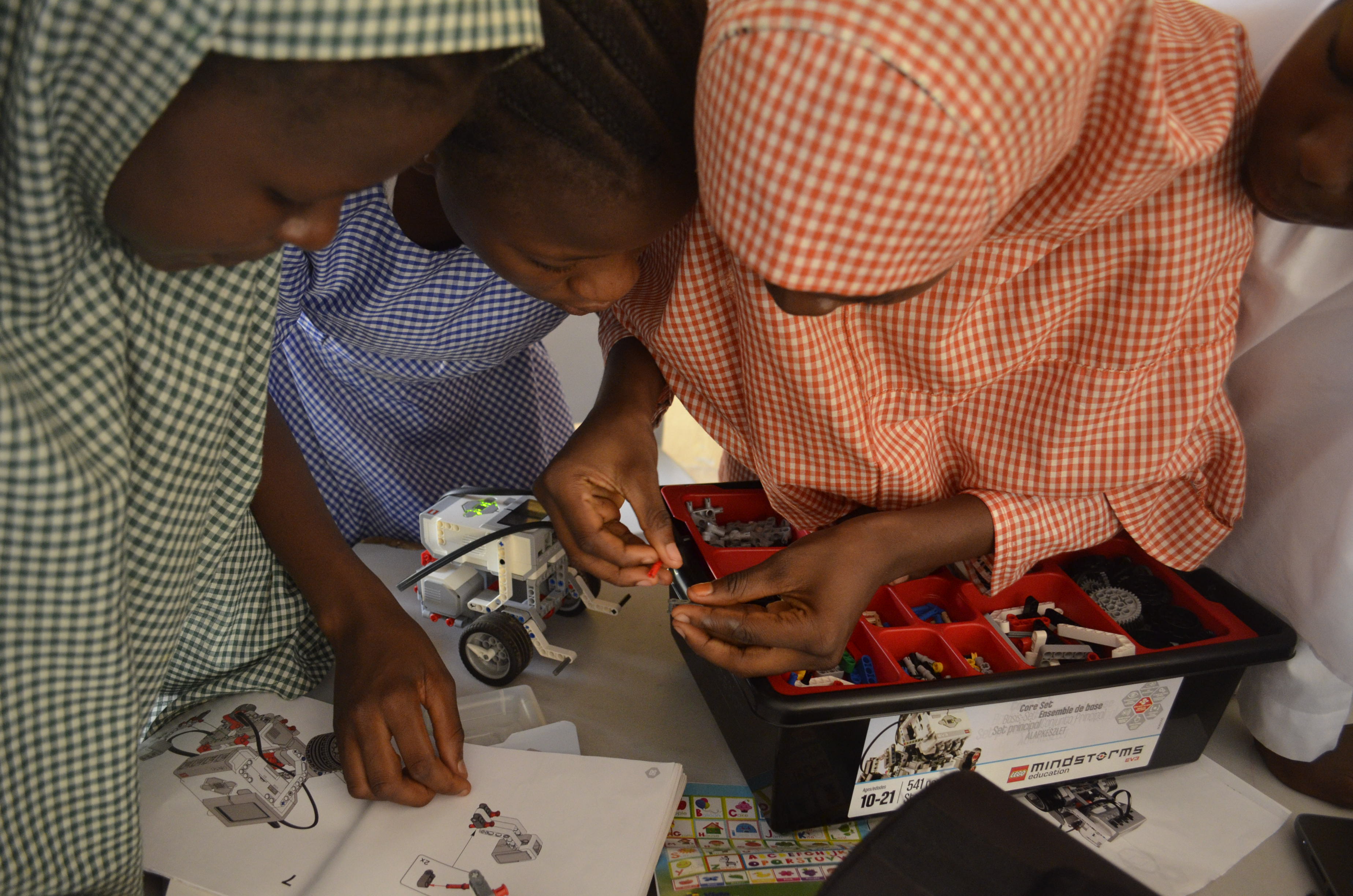

A group of teenage girls huddle eagerly around a robotic trash collector they’ve just built, while others rummage through tool kits and test virtual reality headsets. Infectious laughter echoes through the hallway from outside. More young women are trialling their solar-powered phone chargers and solar ovens, in the shadows of the majestic Aso Rock, which rises over the Nigerian capital’s central government district.

Prominently etched on a poster is an old Fanti proverb and quote by Ghanaian-born missionary and teacher, Dr. James Emman Kwefyir Aggrey. It reads: “If you educate a man, you simply educate an individual. But if you educate a woman, you educate a nation.”

Aggrey’s words represent a view shared by co-founder and president of the Visiola Foundation, Lade Araba. She believes that women will transform Africa, if given the platform to contribute to the continent’s development. With this conviction, she set up the foundation where the STEM (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) summer camp on solar power is in full swing today. The foundation’s main aim is to mentor and educate academically bright but disadvantaged African girls and young women in the STEM fields.

“We want to build a network across the continent so that more girls and women see the potential in a STEM career,” states Araba, who hopes the foundation can help foster a pipeline of female African STEM professionals. “If you do not have diversity in STEM, then most of the research, technologies and the products that are being built, will only cater to one gender. It does not make good business sense and could potentially have harmful health impacts.”

A recent World Bank report highlighted the costs of limiting educational opportunity for girls. It estimated that barriers to completing 12 years of education cost countries between $15 and $30-trillion in lost lifetime productivity and earnings.

Araba’s personal experiences have partly inspired the foundation’s origins. Living most of her life outside Africa, she moved from Lagos to Rome when she was four years old, and later studied at a university in the US. Her career, which started in IT, has taken her across the world including development finance work for both the African Development Bank and the United Nations. Yet it was Araba’s memories of returning to Italy in 2005 which most significantly influence the work she does today.

Growing up in Rome, Araba became aware of the large number of African migrants seeking a better life in the Italian city, but didn’t fully grasp the challenges they faced. “When I returned to the city, I became especially concerned about the young women I met,” says Araba. “For many, the only way to escape poverty was by being in Rome and attempting to make it by any means possible.”

Araba started to invite the young women over to her apartment once a month. “It was an opportunity for us to talk about a lot of things in a safe environment,” she recalls. “We’d share a meal and basically explore education and how that could be transformational for them, as well as discuss scholarship opportunities and degree programmes they could pursue.” The advice and encouragement helped change many of the women’s lives, says Araba, and was the spark behind the foundation.

From its early 2014 origins in a co-working space in Abuja, the Visiola Foundation has grown significantly both in its geographical reach — operating its programmes in a second base in Accra, Ghana — to the diversity of programmes it runs across Nigeria.

The foundation has three institutional partnerships with Ashesi University College, Lead City, and Bayero University, which provide scholarships for girls from marginalised backgrounds to pursue STEM degrees. The popular summer camps have also seen more than 150 teenage girls learn how to code, build robots and renewable energy products, as well as conduct scientific experiments, with support from local companies such as Schneider Electric West Africa and Young Engineers Nigeria.

Araba emphasises the importance of early exposure to STEM subjects, as well as acknowledging the barriers many young African women regularly face. “We’re working with girls from many different backgrounds, cultures and religions, with lots of external influences, “she says. “The plight of girls in northern Nigeria is heart-wrenching. One of the biggest pressures there is early marriage, where having a career or contributing to society are not seen as priorities for girls.”

Statistics released by the National Universities Commission (NUC) of Nigeria further highlight the country’s dire situation, where only 14 to 20% of university graduates studying computer science, technology and engineering are female. Araba suggests many girls lose confidence between junior and secondary school. “We realised that by the time girls get into secondary school their confidence has been shot,” she says. “We want to address the stereotypes and really build their confidence from an early stage.”

Through its partnership with the Federal Capital Territory Secondary Education Board in Nigeria, the foundation runs after-school STEM Clubs. The programme covers 15 government secondary schools, and since 2016 has taught robotics, science, engineering and computer programming to more than 950 junior and senior secondary school girls.

Araba reiterates the need for modernising the country’s curriculum and digitising classrooms. “In the UK for example, children as young as five are learning how to code and are building apps,” she states. “In our case, we get students who come to us at the age of 17 or 18 and that is the first experience they’ve ever had using a computer. They’re already at a disadvantage.” The foundation has set up coding boot camps for young women between 17 and 25 years’ old hoping to encourage them to learn how to leverage technology to solve challenges.

According to the UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS) data, less than 30 per cent of the world’s researchers are women. In Nigeria, Africa’s most populous country, just 23.3% of researchers are female. Araba cites many stories showing why these figures need to change, but one particular example stands out. She recalls the motivations of one student applying for a scholarship to study medicine and become a doctor. “One of the things she’d observed in her conservative community was that women have to go to male gynaecologists because there is a dearth of female doctors,” says Araba. “She told us how uncomfortable and embarrassing this was, and how many women were avoiding regular OB/GYN check-ups as a result. It was motivation enough.”

Africa is home to 17% of the world’s population and 25% of the global burden of disease, but produces just one percent of the world’s research output. Plagued by chronic under investment and poor infrastructure, only one percent of global investment in research and development is spent on the continent.

Araba believes if ever there was a time to invest in human capital, it is now. To achieve just the world average for the number of researchers per capita, the continent needs another million new PhDs. Lack of opportunity, however, often sees African researchers move to high-income countries.

“Instead of building our human capital we’re importing it,” reacts Araba, stating the $4-billion African countries collectively spend on hiring STEM expatriates, each year. “We’re losing 20 000 researchers every year to countries like the US. Meanwhile, we’re recruiting scientists from abroad, who must come up with vaccines and medicines to treat tropical diseases that they do not experience in their own countries.”

With high youth unemployment rates, she asserts that Africa’s young people hold the key to solving future challenges, such as climate change and renewable energy. By 2050, a quarter of the world’s working age population will be African and by 2100, half the world’s youth will be from the continent. Araba contends there are lots of companies recruiting for staff in Nigeria, but says a large majority of roles remain unfilled because students do not have the right technical training or skills to carry out the work. Through the foundation’s work, many students have been paired with mentors and also offered short-term internships with industry to gain practical experience in the workplace.

“A lot of African students don’t have the opportunity to do internships, so when they start their careers, it’s actually the first time they’ve been in a corporate setting, which does them a great disservice,” says Araba, who also emphasises the significance of role models. “It’s important for them to see people who look similar, who’ve come from challenging backgrounds, and have overcome those difficulties. It’s very inspirational and helps the girls aspire to greater things.”

Other similar non-profit organisations encouraging STEM education for girls have been springing up across Africa over the past two decades, including the Women’s Technology Empowerment Centre (W.TEC), Girls Coding, and the long-standing Working to Advance Science and Technology Education for African Women (WAAW). Many have developed strong mentor networks with African scientists across the world.

“The work the foundation undertakes is contributing towards a more equal future with greater shared prosperity,” says Dr Ozak Esu, a UK-based Nigerian engineer and mentor at the Visiola Foundation. She continues: “One where young girls and women feel empowered to participate in high-order cognitive professions in STEM and thrive for the benefit of the economy.”

As the summer STEM camp draws to a close for another year at Visiola’s headquarters, the glowing reviews from the teenage participants are flooding in. Seventeen-year-old Aisha now has the confidence to pursue her dream of becoming a computer scientist, while Anita, 15, is keen to become a mechanical engineer and encourage people to use renewable energy. However, it’s left to one of the youngest students, Grace, 14, to sum up what makes these programmes so special. “It was an awesome experience, one I’ll never forget,” she says. “And do you know what, I built these projects in the company of young, beautiful and talented girls, who prove why STEM girls rock.”