(John McCann)

State-owned energy company PetroSA has offered the use of its infrastructure in Mossel Bay to Total in the hope that it will get feedstock from the French oil company’s new offshore gas find off the southern coast.

This depends on how Total decides to develop the gas condensate it discovered, said Bongani Sayidini, PetroSA’s acting chief executive.

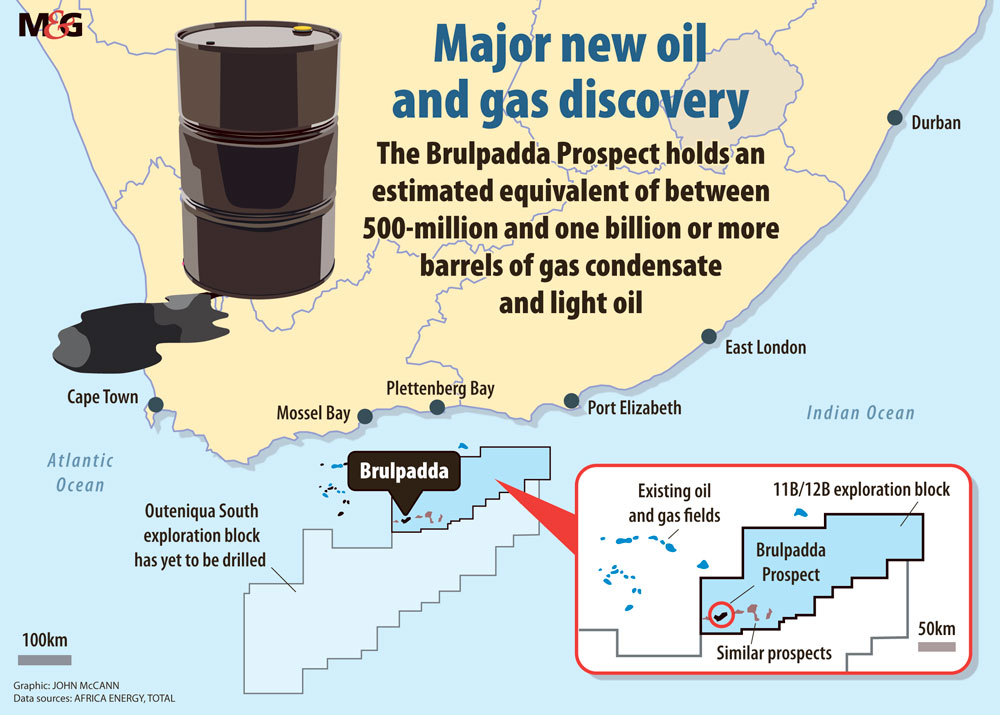

Total and its partners announced this past Thursday that a significant gas condensate discovery had been made in Block 11B/12B in the Outeniqua Basin, 175km off the southern coast.

The discovery has been called a “game-changer” and “catalytic” by President Cyril Ramaphosa and industry experts, who say the find could have a material effect on the country’s economy.

One immediate potential beneficiary is the loss-making PetroSA, whose gas-to-liquid plant in Mossel Bay has been running below at least 50% of its capacity for more than two years, according to Sayidini.

The state-owned entity’s infrastructure also includes pipelines close to Total’s offshore find.

Sayidini said PetroSA has reached out to Total and expressed its interest in receiving feedstock from the French oil company. He said PetroSA also highlighted that its offshore infrastructure could “be potentially enabling for Total and ensure that [it] moves quicker in monetising this gas and condensate discovery because there is already infrastructure they could tap into”.

Should Total piggyback on PetroSA’s infrastructure, Sayidini said the time taken to go from exploration to commercial fuel production could be “significantly cut” from the estimated eight years by possibly as much as half.

Total plans to drill four more wells in the area, and chief executive Patrick Pouyanné told Reuters that it is estimated there is about one billion barrels of gas condensate in the block.

On whether the struggling state-owned entity would be able to afford the gas provided by Total, Sayidini said PetroSA was already processing and importing gas at market rates, which indicated that it can afford the feedstock at the “right price”.

Sayidini said that condensate is a high-cost commodity on its own and, when imported, the price was compounded by logistical costs.

Last year the auditor general expressed concern about PetroSA’s ability to remain a going concern, after consecutive years of substantial losses. In the 2017–2018 financial year it recorded losses of R666-million. This was preceded by a loss of R1.6-billion in the 2016–2017 financial year. During the 2014-2015 financial year, PetroSA recorded net operating losses of R14.6-billion which, at the time, was one of the biggest losses declared by a state-owned entity.

Total’s discovery has renewed the urgency for the government to finalise the separation of upstream oil and gas legislation from the Minerals, Resources and Petroleum Development Act (MPRDA).

Mineral Resources Minister Gwede Mantashe said the gas discovery further confirmed that government’s decision to separate legislation for oil and gas from minerals was the correct one. “We are moving with speed to finalise this legislation, to ensure that it is presented as soon as the sixth Parliament sits,” he said in a statement released after the find was announced.

A previous attempt to change the legislative framework with the MPRDA Amendment Bill, introduced in 2013, was mired in legislative wrangling and contributed to extended regulatory uncertainty in the mining industry, before it was withdrawn last year. This means the MPRDA of 2002 as amended in 2008 continues to apply.

The 2013 amendment Bill proposed wide-ranging changes to provisions governing the petroleum sector, particularly the participation of the state and historically disadvantaged people.

One of the controversial proposed changes at the time was the requirement that the state be granted a 20% free carried interest in all new exploration and production rights. It meant the state would have had a stake in operations without making any financial contributions.

In addition, the government would also have been entitled to a further participation interest of up to 30% depending on the size of the discovery, coming in the form of either a carried interest, production share agreements or purchased at an agreed price.

It is not clear whether the yet-to-be-published legislation will include similar terms.

Lloyd Christie, head of ENSafrica’s natural resources and environment department, said the demands by the government would have to be placed against the fledgeling status of oil and gas in the country. The industry is relatively underdeveloped and only a few oil and gas discoveries have been made, “which makes exploration still a high-risk investment with low prospects of finding commercial quantities of oil and gas”, he said.

Both Christie and Barrisford Petersen, an international gas and oil expert and the managing director of BBP Law, agreed that stand-alone petroleum laws were necessary and they would have to enable flexible and stable fiscal terms that will attract investment from international oil companies with the financial muscle for exploration, such as Total.

“We don’t want to make the same mistakes that we made in the mining industry in the oil industry where the majority of the ownership in the mining industry is by foreign companies but on the other hand, we can’t afford to play in this high-risk game,” Petersen said.

He added that the government needed to develop petroleum legislation based on the “principles of production sharing”. One of the principles would be that the South African government owns the resource instead of the production company that has the exploration or production right.

In such a production-sharing model a country’s government awards the execution of exploration and production activities to an oil company that takes on the full financial risk to explore for and produce the resource. This operational cost is then recouped in the production phase from money made from selling the resource, and the profit is shared between the government and the company.

Petersen said the state could allocate an appropriate amount of the proceeds from the profit into a sovereign wealth fund.

Tebogo Tshwane is an Adamela Trust business journalist at the Mail & Guardian