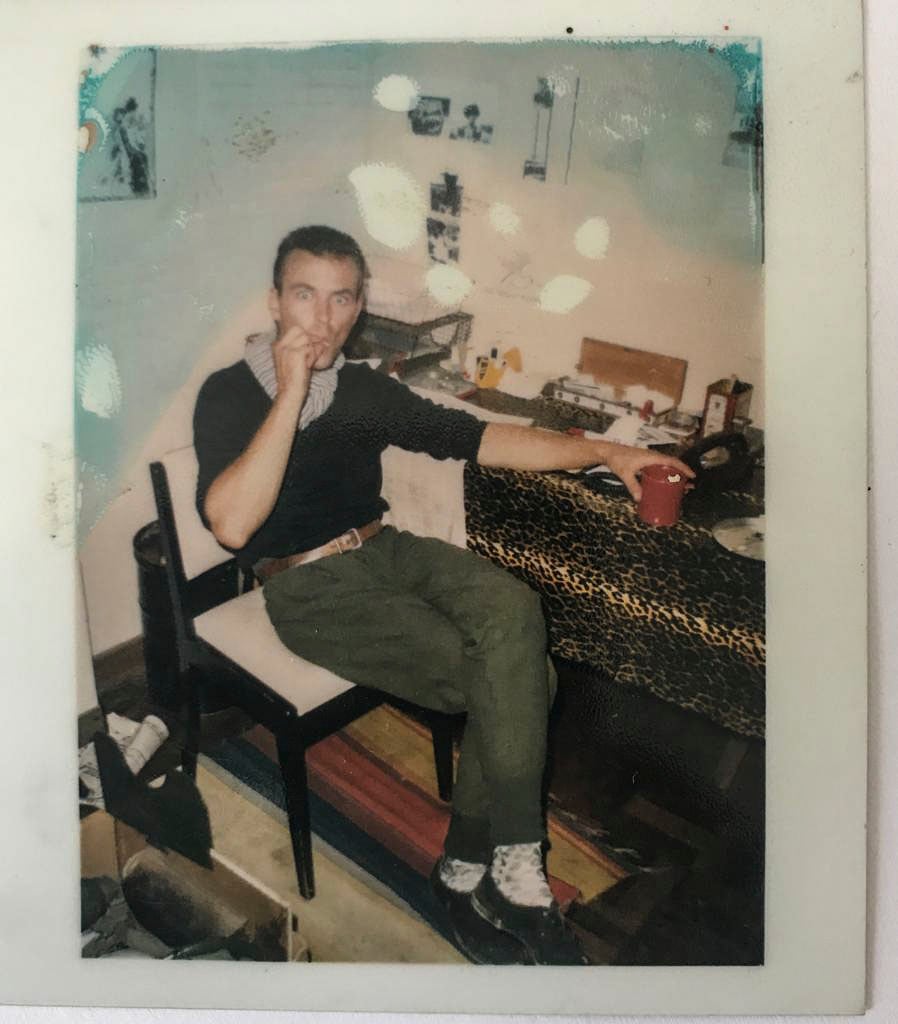

Drumming up support: Carsten Rasch with reggae outfit National Wake. (Supplied)

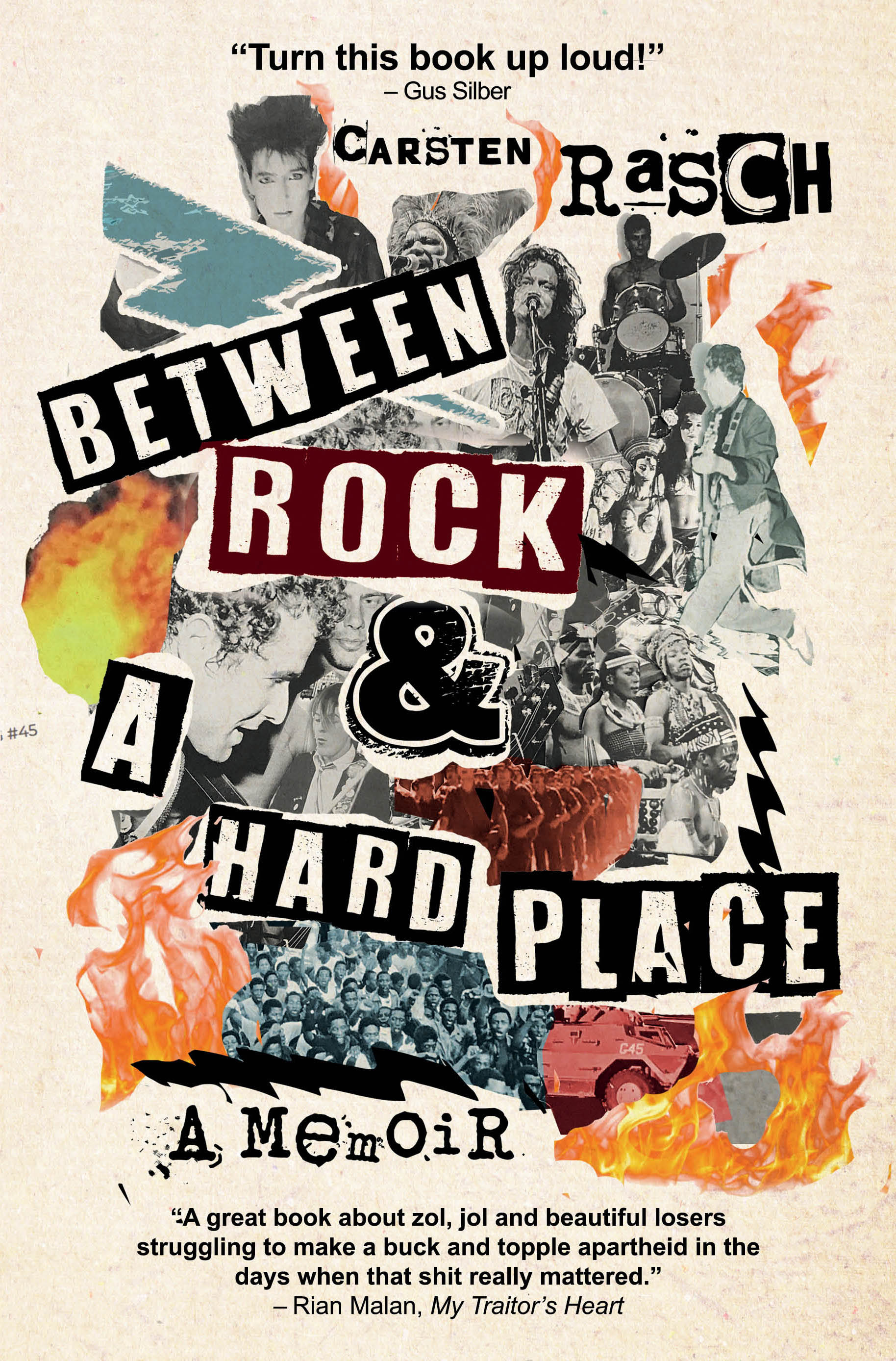

BETWEEN ROCK AND A HARD PLACE

by Carsten Rasch (MF Books)

Carsten Rasch, known generally as Cas, has written a rambunctious memoir of the late 1970s and early 1980s in South Africa’s nascent “alternative” music scene. It wasn’t yet called alternative, and it was largely white, with some crossover into a black musical world — mostly Rastas, with a bit of Amampondo and the Malopoets. It was alternative because it was unlike the mainstream, squeaky-clean and nonthreatening pop scene that got its music on the state-run radio and sometimes even television.

This kind of musical and social adventure was chiefly inspired by punk in Britain, catching up with that angrily rebellious movement just as punk died, along with Sid Vicious, in New York in 1979. But that didn’t matter. What was inspiring about punk was its fuck-you attitude, and white youths feeling the repression of the apartheid years, responded wholeheartedly. Before even the political repression, such young white people were kicking against the social repression — a suffocating upright-Calvinist Afrikaner self-righteousness.

Behind punk, of course, and equally influential, though perhaps in a vaguer way, was the hippie revolution that began in the United States in the 1960s. Rasch describes himself in those years as a “hippie punk”, and that’s about right, if you include in “hippie” the influence of the Rasta sensibility.

It had a lot to do with getting out of your head, too, of course, but there was little available in the way of “hard” drugs (cocaine, heroin), so it was about pharmaceuticals such as Obex and Vesparax and dagga, dagga, dagga.

From Stellenbosch, where Rasch was a (failed) student, to Cape Town and Johannesburg, with some unlikely venues in between, Rasch and his friends helped to build this alternative music scene. They ran little clubs, developing their own jol, or set up music festivals. Not that these festivals always came off.

There’s a hilarious episode in which Rasch and his friend Hoffie, the latter with his face bandaged like a mummy because of a camping accident, try to convince the Bantustan government of the then Transkei that having a music fest in Port St Johns would be a good idea. They thought they could get money from the Transkei government to get the festival going, but the relevant minister wanted money from them to give it the go-ahead.

Carsten Rasch and his friend Hoffie travelled the country trying to set up music festivals, sometimes with hilarious consequences. (Supplied)

Rasch crisscrossed the country in his kombi, really a decommissioned ambulance with a steel shelf in it, on which he slept; it was filled with all his worldly goods. That’s when he wasn’t living in a commune (outlawed in Stellenbosch at the time) or a barely furnished flat in Yeoville and avoiding the grasp of the apartheid military.

The story of Between Rock and a Hard Place is a picaresque, with trips to unlikely places such as Krugersdorp and Trichardt included.

In the former, the bands and promoters got locked out of the city hall they’d booked, under slightly false pretences, to hold a concert. In the latter, they got a slot in a run-down bar eager for entertainment (that included an all-in fist fight). Rasch provides a picture of a place and a time now surely vanished: “The wall behind the bar counter is plastered with Scope centre spreads interspersed with a few stuffed antelope heads, a string of panties and bras adding the finishing touch.”

A crusty lone drinker at the bar, obviously a representative of that amazingly self-righteous Afrikaner Calvinism, interrupts his reading of a photo-story and his spitting into a bucket to condemn the newly arrived hippie punks as “people of Sodom and Gomorrah”.

The book is a full, lively account of this time in the life of South Africa’s alternative music scene, seething with the bands and the vivid characters who played in them, hung around them or formed their audiences. The bands are too many to mention, and most lasted barely a year or two, but they left an indelible skid mark on our musical history.

Between Rock and a Hard Place is highly entertaining, a stagger down memory lane for anyone who participated and, surely, an eye-opener for many who didn’t. There was a whole lot of crazy life there, a life opposed to the deathliness of Calvinist apartheid, and Rasch’s account is the very enjoyable, even inspiring, story of a wasted youth you could only call well-spent.