Tripping: The journey to Conakry in Guinea from Bamako in Mali involves a taxi trip interrupted by negotiations with officials at the border and at roadblocks. (Michael Runkel)

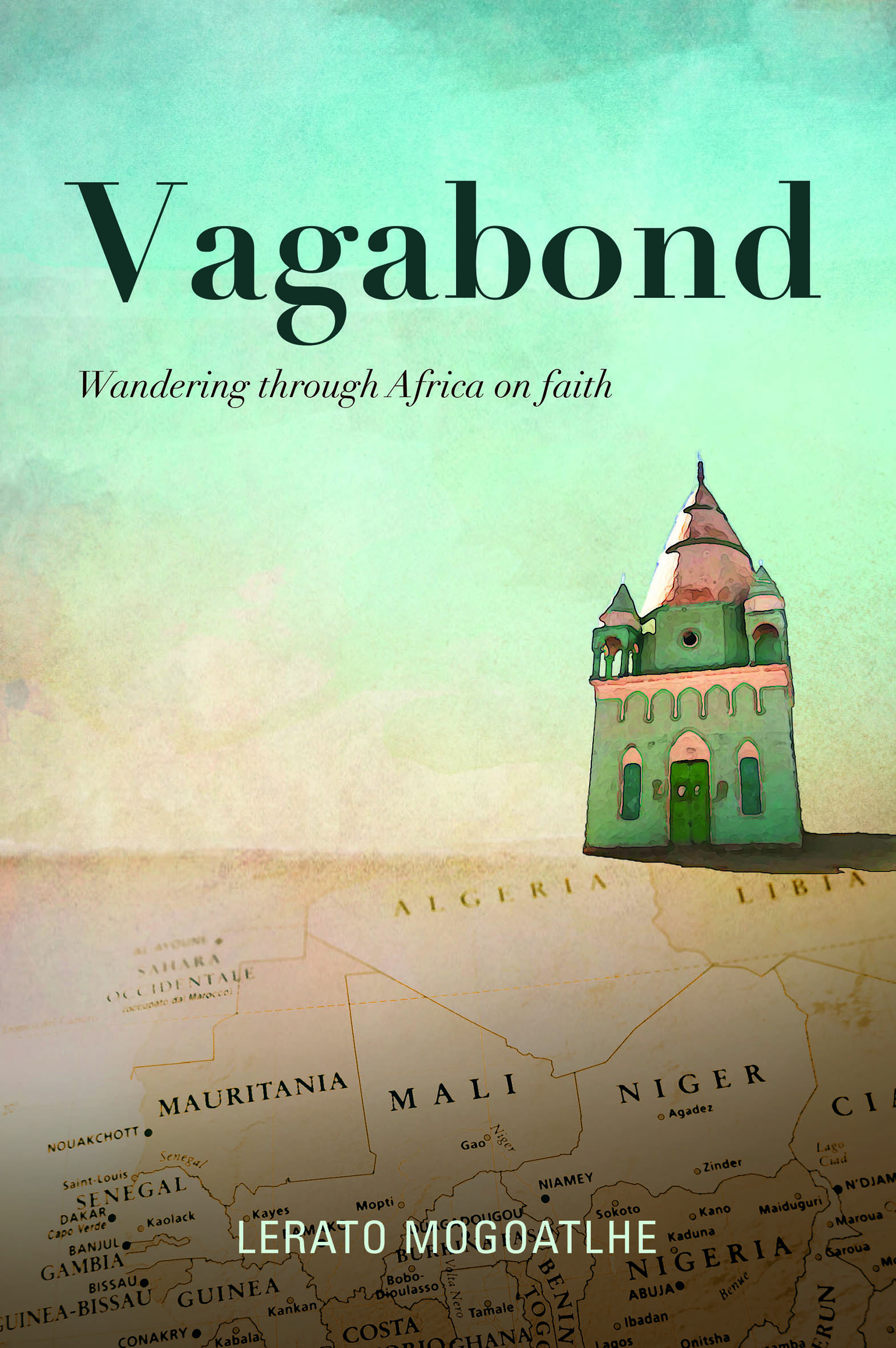

VAGABOND: WANDERING THROUGH AFRICA ON FAITH by Lerato Mogoatlhe (Blackbird Books)

Aisha (July 2009)

‘Border post” is not just a sign. It’s also an announcement of impending combat. Out of all the battles raging on this war-torn continent, there’s nothing quite like the stand-off between travellers and border control officials, or uniforms, as I call them. Provoke a uniform with so much as a hello and bombs will drop — invalid passport, expired visa, missing yellow fever vaccination and a litany of problems that only exist in the uniforms’ heads. It’s as if they’re competing to be the Idi Amins of border posts. Like all such encounters, this one is brutal, as I discover in Kouremale, Mali, on my way to Conakry. Everyone inside the one-room office puts franc notes in their passports when handing them over. I stand my ground when the uniform says my visa has expired. “You have to pay 5 000 francs.” He waves me away while I presumably look for the money in my bag. His next victim is a woman who is also in my taxi to Conakry.

Guinean fishermen tend to their boats at the port of Boulbinet in Conakry. (Joe Penney/Reuters)

Her one-page travel document is accompanied by a 1 000 franc note. She pulls me outside, where she “go beg” me to “jus pei de man”. The thing is, I just don’t feel like it. I’ve already paid too damn much to be here. Or, as I rattle off to my “sistoh”, “In the 15 years that I have been on my period, I have only ever used Lil-Lets; it’s the most intimate relationship of my life, and my constant in a life that changes every few minutes. I now use OB, as if a period is a spelling bee. I haven’t had privacy in a year and spent the last four months living in a house with 10 men. I don’t have a sex life and clean up ‘number two’ with water, soap and my left hand, and here’s a further payment for you — I love it for being cleaner than the toilet-paper way I’ve known all my life. I have paid with my money, my comfort, my everything. Hell, I don’t even look like the Lerato I’ve known all my life — excuse me if I’m not in the mood to bribe.”

The way my sistoh looks at me storming back to the office, it’s as if she knows a bigger fool is yet to be born. It doesn’t matter. My visa is valid. The uniform persists. We go around in circles until it turns out that he’s right. Technically. I sleep when others leave the bus to get their passports stamped at the border between Mali and Ivory Coast. I don’t have a date of entry.

“You have to go back to Bamako,” he says.

“Other people are renewing their visas here. Why do I have to go back?” I fume.

“Because,” he smiles, “I say so.”

“My sistoh, why you de no listen?” the woman in the taxi to Conakry says when I offload my bags.

All the cars I approach are full, and it’s too late in the day for a taxi. The uniform walks over to carry my bags to where he’s sitting with three colleagues, brewing mint tea. We spend hours under the full moon listening to Toumani Diabaté and Ballaké Sissoko’s New Ancient Strings.

He asks a trucker to give me a lift back to Bamako. My lost temper costs me 37 050 francs: 15 000 for a visa, 2 000 in passport pictures, 350 in taxi fares between Djicoroni Para and the immigration office in Hamdallaye, and another 20 000 on a ticket to Conakry. I really need to be locked away when I’m premenstrual.

I keep my mouth shut at the Bankan crossing in Guinea four days later when a uniform asks me to put money in my passport.

My hand digs willingly into my bag at an immigration checkpoint a few kilometres later. This office has bamboo walls, a scratched table, pens with chewed lids, and a dog-eared notebook into which the two uniforms write our names and passport numbers. We hold travel papers in one hand and money in the other. The uniform demands 5 000 francs to buy airtime to call me, to make sure I arrive safely in Conakry. The long, winding road to Conakry starts out on a smooth, tarred road before hitting the most potholed stretch in this infinitely potholed continent. At the second and third road blocks, only our driver, another Mohammed, steps out of the car.

He pays with a smile that turns into a snarl the moment he’s back in the taxi. “Bandits,” he hisses.

Guinea is too beautiful for the six road blocks we go through to ruin the experience for me. The landscape looks something like a rain forest, with houses and people surrounded by a chain of hills and valleys and mountains that stretch on and on, some shrouded by mist, poking into grey skies that look like they’re a squeeze away from pouring with rain.

I know the fourth roadblock is trouble when two uniforms shine their flashlights into the taxi.

Mohammed’s bribe is just a start. They want us all to pay. The uniforms interrogate me with the usual questions about why I’m in Guinea. One uniform declares my visa invalid, and my passport expired. I have time and legitimate papers; I’m fighting this one out until I win. After an impasse is reached between me and the uniforms, they order Mohammed to follow them to the police station. My passport is checked as if I’m a suspected terrorist before a new problem emerges. My medical card is invalid. It’s more than R4 000 spent on multiple vaccinations because, to quote the Lonely Planet travel guide quoting the World Health Organisation, I dare not travel around Africa without immunisation from diphtheria, tetanus, measles, mumps, rubella, polio, hepatitis B and a host of other diseases.

We wait until morning for the station commander. He starts by angling for a bribe, but after a fed-up guy in the taxi tells him that I’m a journalist, he relents and apologises for wasting my time. The town is wide awake when we leave the police station. I get to see the dense, green plateaus that make up the Fouta Djallon region.

Mohammed stops to pick up a parcel of sacks bulging with raw plantain still attached to the stalks, to give to someone in Conakry. We are in a valley, misty with dense grey clouds tumbling over a mud house surrounded by tall bright-green maize plants.

Our next road block is in Coyah, a village so beautiful it has a brand of mineral water named after it. A group of boys bathe in a stream flowing from a small waterfall. Mobile kitchens sell fat cakes, boiled eggs and bread.

We follow Mohammed and the uniform who’s collecting our passports. I smile my way out of parting with more francs. An aggressive man wearing a luminous lime car-guard’s top runs up to the taxi when it crawls through traffic at the last roadblock in Conakry. “L’argent,” he thunders, hands reach into the window to start collecting money while the car moves.

Into my purse my hand goes again to get 5 000 francs. I get off the taxi with my education in crossing African borders complete: you have to know when to shut up and pay.

My final destination is the island village of Soro. I get into the wrong boat and end up in Kassa. I sit at the pier while it empties out, waiting for a man who will inevitably show up to play my hero.

Matthew sees me sitting here while surveying the pier from the barracks. He’s in the army and wants to search my bags to make sure that I’m not breaking any laws. He carries my bags up a stony footpath to the barracks. He goes through them with another male officer and a female one. The Diallos are married and spend most of their nights at her place at the barracks.

He offers me his place. It’s one of three rooms that the owner of the property, Monsieur Sylla, rents out to male soldiers. Monsieur Sylla is a sour old man who regards me with suspicion when I go into their house to greet and introduce myself.

Matthew is at my door first thing in the morning to walk me to Soro. There are no boats between the two villages, no electricity except for four hours at night when a kiosk fires up a generator, and the villagers pay to charge their cellphones at the multi-adaptor.

We walk through narrow spaces between houses to the wild side of the island where the branches of palm trees sway in the wind. Litter sticks to the vegetation. The clouds are dark grey and the ground wet from the rain. The rainy season is six months of incessant downpours. We go back to the only main street, walking along the shore, past houses with paint that’s been washed out by water and time, jumping over the small furrows between some houses.

The ocean is grey and still. We get to a stretch of about 600 metres, bordered by mud houses, then walk past two big brown rocks on either side and keep walking until we get to Soro.