Hallelujah: Gospel choirs, such as the junior choir at the Commandment Keepers Congregation in New York, were founded by Thomas Dorsey. (Three Lions/Getty Images)

The enslaved Africans who first arrived in the British colony of Virginia in 1619 after being forcefully removed from their natural environments left much behind, but their rhythms associated with music-making journeyed with them across the Atlantic.

Many of those Africans came from cultures where the mother tongue was a tonal language. That is, ideas were conveyed as much by the inflection of a word as by the word itself. Melody, as we typically think of it, took a secondary role and rhythm assumed major importance.

For the enslaved Africans, music – rhythm in particular – helped forge a common musical consciousness. In the understanding that organized sound could be an effective tool for communication, they created a world of sound and rhythm to chant, sing and shout about their conditions. Music was not a singular act, but permeated every aspect of daily life.

In time, versions of these rhythms were attached to work songs, field hollers and street cries, many of which were accompanied by dance. The creators of these forms drew from an African cultural inventory that favuored communal participation and call and response singing wherein a leader presented a musical call that was answered by a group response.

As my research confirms, eventually, the melding of African rhythmic ideas with Western musical ideas laid the foundation for a genre of African-American music, in particular spirituals and, later, gospel songs.

Spirituals: A journey

John Gibb St. Clair Drake, the noted black anthropologist, points out that during the years of slavery, Christianity in the U.S. introduced many contradictions that were contrary to the religious beliefs of Africans. For most Africans the concepts of sin, guilt and the afterlife, were new.

In Africa, when one sinned, it was a mere annoyance. Often, an animal sacrifice would allow for the sin to be forgiven. In the New Testament, however, Jesus dismissed sacrifice for the absolution of sin. The Christian tenet of sin guided personal behavior. This was primarily the case in northern white churches in the U.S. where the belief was that all people should be treated equally. In the South many believed that slavery was justified in the Bible.

This doctrine of sin, which called for equality, became central to the preaching of the Baptist and Methodist churches.

In 1787, reacting to racial slights at St. George Methodist Episcopal Church in Philadelphia, two clergymen, Absalom Jones and Richard Allen, followed by a number of blacks left and formed the African Methodist Episcopal Church.

The new church provided an important home for the spiritual, a body of songs created over two centuries by enslaved Africans. Richard Allen published a hymnal in 1801 entitled “A Collection of Spirituals, Songs and Hymns,” some of which he wrote himself.

His spirituals were infused with an African approach to music-making, including communal participation and a rhythmic approach to music-making with Christian hymns and doctrines. Stories found in the Old Testament were a source for their lyrics. They focused on heaven as the ultimate escape.

Spread of spirituals

After emancipation in 1863, as African-Americans moved throughout the United States, they carried – and modified – their cultural habits and ideas of religion and songs with them to northern regions.

Later chroniclers of spirituals, like George White, a professor of music at Fisk University, began to codify and share them with audiences who, until then, knew very little about them. On Oct. 6, 1871, White and the Fisk Jubilee Singers launched a fundraising tour for the university that marked the formal emergence of the African-American spiritual into the broader American culture and not restricted to African-American churches.

Their songs became a form of cultural preservation that reflected the changes in the religious and performance practices that would appear in gospel songs in the 1930s. For example, White modified the way the music was performed, using harmonies he constructed, for example, to make sure it would be accepted by those from whom he expected to raise money, primarily from whites who attended their performances.

As with spirituals, the gospel singers’ intimate relationship with God’s living presence remained at the core as reflected in titles like “I Had a Talk with Jesus,” “He’s Holding My Hand” and “He Has Never Left Me Alone.”

The rise of gospel

Gospel songs – while maintaining certain aspects of the spirituals such as hope and affirmation – also reflected and affirmed a personal relationship with Jesus, as the titles “The Lord Jesus Is My All and All,” “I’m Going to Bury Myself in Jesus’ Arms” and “It Will Be Alright” suggest.

The rise of the gospel song can, in part, be tied to the second major African-American migration that occurred at the turn of the 20th century, when many moved to northern urban areas. By the 1930s, the African-American community was experiencing changes in religious consciousness. New geographies, realities and expectations became the standard of both those with long-standing residence in the north and those who had recently arrived.

The new arrivals still welcomed the jubilant fervour and emotionalism of camp meetings and revivals that included the ring shout, a form of singing that in its original form included singing while moving in a counterclockwise circle, often to a stick-beating rhythm.

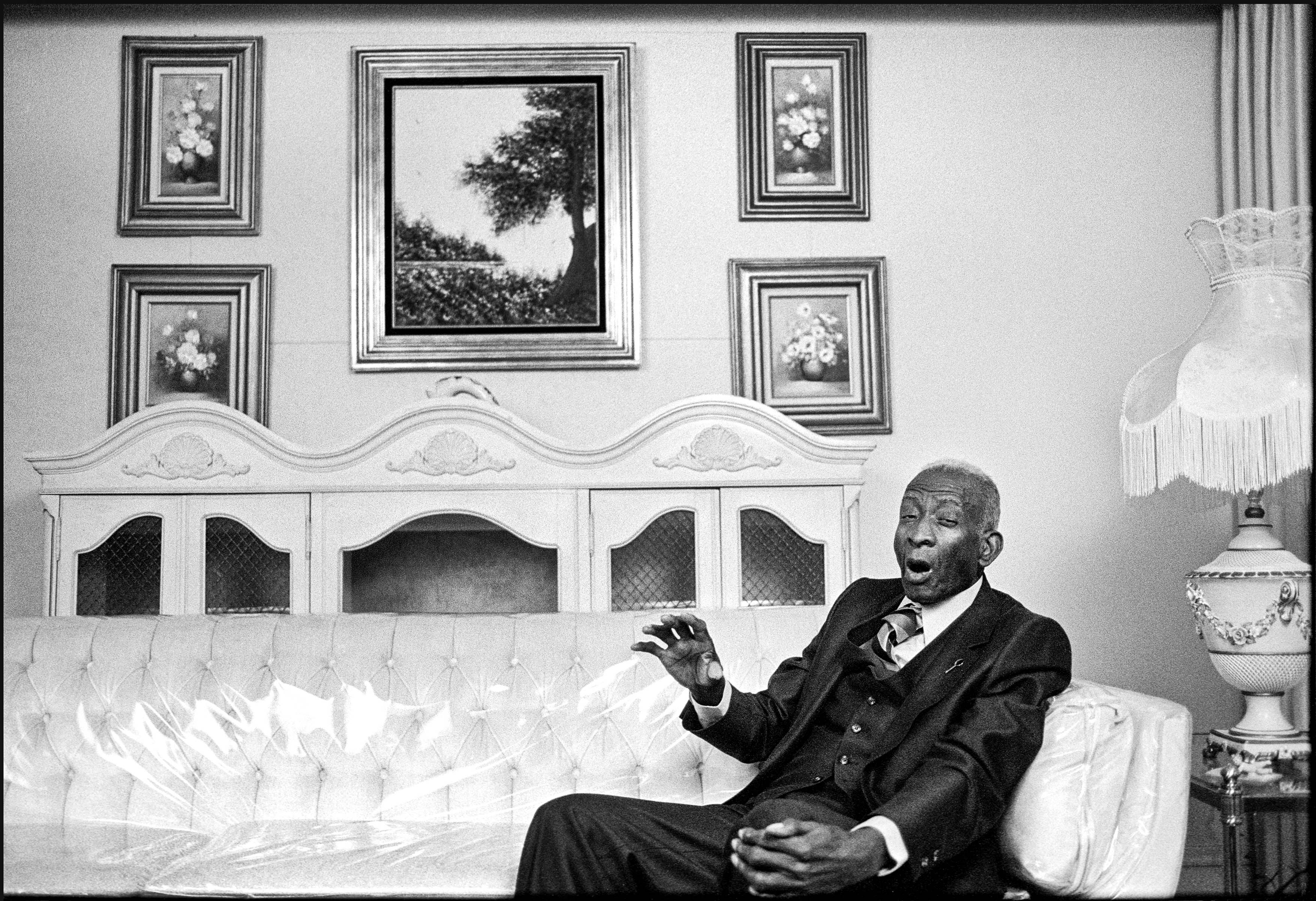

Father of African American gospel music, Thomas A. Dorsey. (Chuck Fishman/Getty Images)

The 1930s were also the era of Thomas A. Dorsey, the father of gospel music. A former bluesman, who performed under the name of Georgia Tom, Dorsey rededicated his life to the church after the tragic death of his wife and child. He began a campaign to make gospel acceptable in church. His first gospel song published was If You See My Saviour. He went on to publish 400 gospel songs, the best known being Take My Hand, Precious Lord.

Dorsey was also one of the founders of the first gospel chorus in Chicago and, with associates, chartered the National Convention of Gospel Choirs and Choruses, the precursor to gospel groups in today’s black churches.

In the 1930s, black gospel churches in the north began using the newly invented Hammond organ in services. This trend quickly spread to St Louis, Detroit, Philadelphia and beyond.

The Hammond was introduced in 1935 as a cheaper version of the pipe organ. A musician could now play melodies and harmonies but had the added feature of using their feet to play the bass. This allowed the player to control melody, harmony and rhythm through one source.

The Hammond became an indispensable companion to the sermon and the musical foundation of the shout and praise breaks.

Solo pieces within the service imitated the rhythms of traditional hymns in blues-infused styles that created a musical sermon, a practice still common in gospel performances.

Gospel’s journey continues today producing musicians of extraordinary dedication who continue to carry the word.

This an edited version of African rhythms, ideas of sin and the Hammond organ: A brief history of gospel music’s evolution, originally published in The Conversation