(John McCann/M&G)

Bloated, excessive and overweight — that has been the Cabinet for more than 10 years. But, with the culling that President Cyril Ramaphosa is expected to do, the savings will be Nkandla-sized

THE BILL

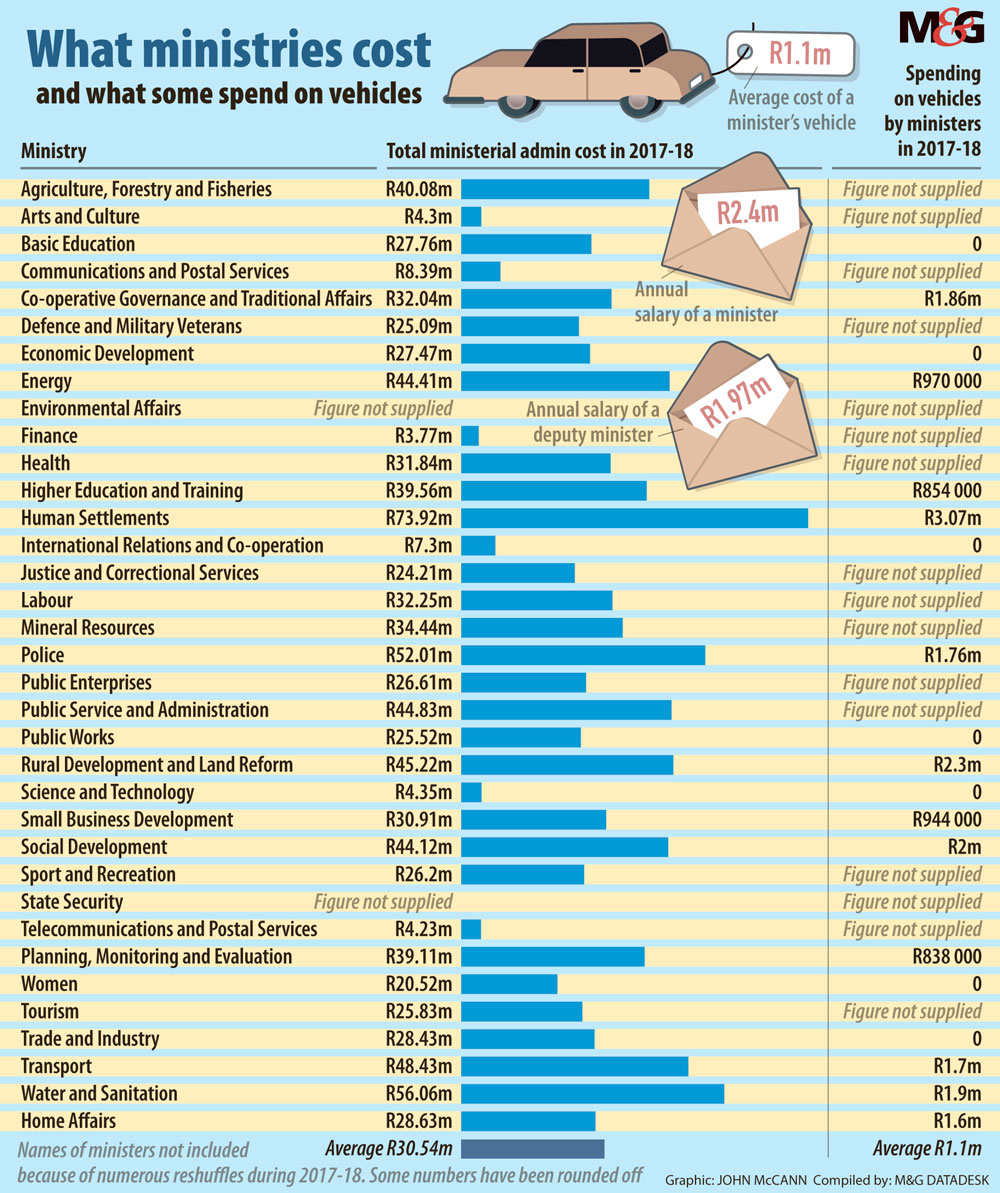

The state has had to fork out more than R1-billion in the past financial year on ministries’ administration costs alone. The Cabinet, which former president Jacob Zuma increased in 2009, currently has 35 ministers and 36 deputies. It is expected to be slimmed down next week.

The Mail & Guardian analysed available numbers to see how much a minister costs, and how much that slimming exercise will save.

According to the annual reports of all 35 government departments, the ministerial administration cost of these departments was an average of R30.5-million in the 2017-2018 financial year.

Administrative costs include the upkeep of ministers and deputy ministers whose expenses include cars, housing benefits, security, travel and advisers or people in the minister’s inner circle and other privileges set out in the ministerial handbook — drafted in 2007.

According to the independent commission for the remuneration of public office bearers, the annual salary of a minister is R2.4-million. Their deputies earn just under R2-million a year. These salaries, which increase each year, mean the state has had to cough up more than R84-million for ministers and R71-million for their deputies.

On administrative costs and ministerial salaries alone, Ramaphosa could save more than R300-million a year if he cut down his Cabinet by 10 members.

Thokozani Chilenga-Butao, an associate lecturer in the department of political studies at the University of the Witwatersrand (Wits), said the fact that different finance ministers have referred to the cost of ministerial spending is an indication that it is high by treasury standards.

“Former finance minister Pravin Gordhan referred to the limit of the type of vehicle [which ministers are allowed], which shows that the cost can balloon or get out of control. There is some sort of standard that should be upheld,” she said.

THE CARS

The average cost of vehicle expenditure amounts to R1.1-million per minister per year. Most ministers own two vehicles — one for Gauteng, where many reside, and another for Cape Town, to travel to and from Parliament.

Although there are big spenders, some ministers have kept their cars for more than five years. Ebrahim Patel, the minister of economic development, seems to be an exception to the splurgers. He still uses two Toyota Fortuners bought in 2010 and 2011 at a cost of R411 372 and R445 475, respectively.

Thuli Nhlapo, spokesperson for the social development minister, Susan Shabangu, told the M&G that a R1.3-million vehicle was purchased for the Pretoria office to replace the vehicle bought by the minister’s predecessor, Bathabile Dlamini, in 2016-2017.

This vehicle was allegedly involved in an accident and had to be written off in December 2017. When Dlamini’s ministry was contacted for details of the alleged accident, the M&G was referred to Parliament.

Two years ago, in a parliamentary response, Dlamini said she and her deputy, Hendrietta Bogopane-Zulu, spent R1.3-million on a luxury BMW and R1.1-million on a Jeep Grand Cherokee.

According to Nhlapho, besides replacing the car that was written off, Shabangu also spent a further R778 508 for a vehicle for the Cape Town office because the car that was used by Dlamini had travelled more than 120 000km. According to

the ministerial handbook, this meant it had to be replaced, she said.

The human settlements minister, Nomaindia Mfeketo, has a penchant for luxury German cars. She bought two Audi S8s in March— one for Cape Town and the other for Pretoria — at a total cost of R3-million. Her department also has the highest ministerial administrative costs, totalling about R74-million.

All the splurging comes even after government introduced austerity measures for ministers.

According to William Gumede, from the Wits school of governance, South Africa’s Cabinet is similar to those in many other developing countries.

“The rule of thumb is that the bigger the Cabinet, the less development will take place. Generally, there’s also more corruption and incompetence. Historically, countries with smaller Cabinets grow faster and show more genuine development.”

One of the reasons for this is that the bigger the government, the more duplication you have, he said.

“In South Africa we have the department of economic development, the department of trade and industry and treasury — it just doesn’t make sense. Another issue [with big Cabinets] is that there are too many moving parts to get things done. It’s just too big to co-ordinate.”

THE TRAVEL

Although ministerial travel costs for themselves and a spouse can be reimbursed by the government, most ministers do not seem to claim for these expenses. Of the 16 ministers who either responded to the M&G, or to a question from an opposition MP, only three reported to have incurred costs.

Senzeni Zokwana, the minister of agriculture, forestry and fisheries, is said to have spent just more than R300 000 in the past financial year. When Malusi Gigaba was finance minister, the ministry paid close to R800 000 in the same year for his travelling costs.

Gordhan’s public enterprises ministry racked up a R1.7-million bill for ministerial travels in the 2017-2018 financial year.

With the impending cuts next week, hundreds of millions of rands will be saved. But to merge or cut down the number of ministries, competent people will need to be appointed.

Chilenga-Butao said: “That will be the test of Ramaphosa’s tenure — will he appoint the right people for the job?”

THE MERGE

Gumede cautions that, though people on the ground have high expectations regarding the Cabinet cut, the process is slow and people tend not to like the changes.

“The way government reform works is that the restructuring process takes 12 months at best to finalise. During this time, government can’t really execute any new things. People are going to fight you back. Because they’re going to lose their jobs or power,” he said.

Athandiwe Saba heads the Mail & Guardian’s Data Desk. Jacques Coetzee is the Adamela data fellow at the M&G, a position funded by the Indigo Trust