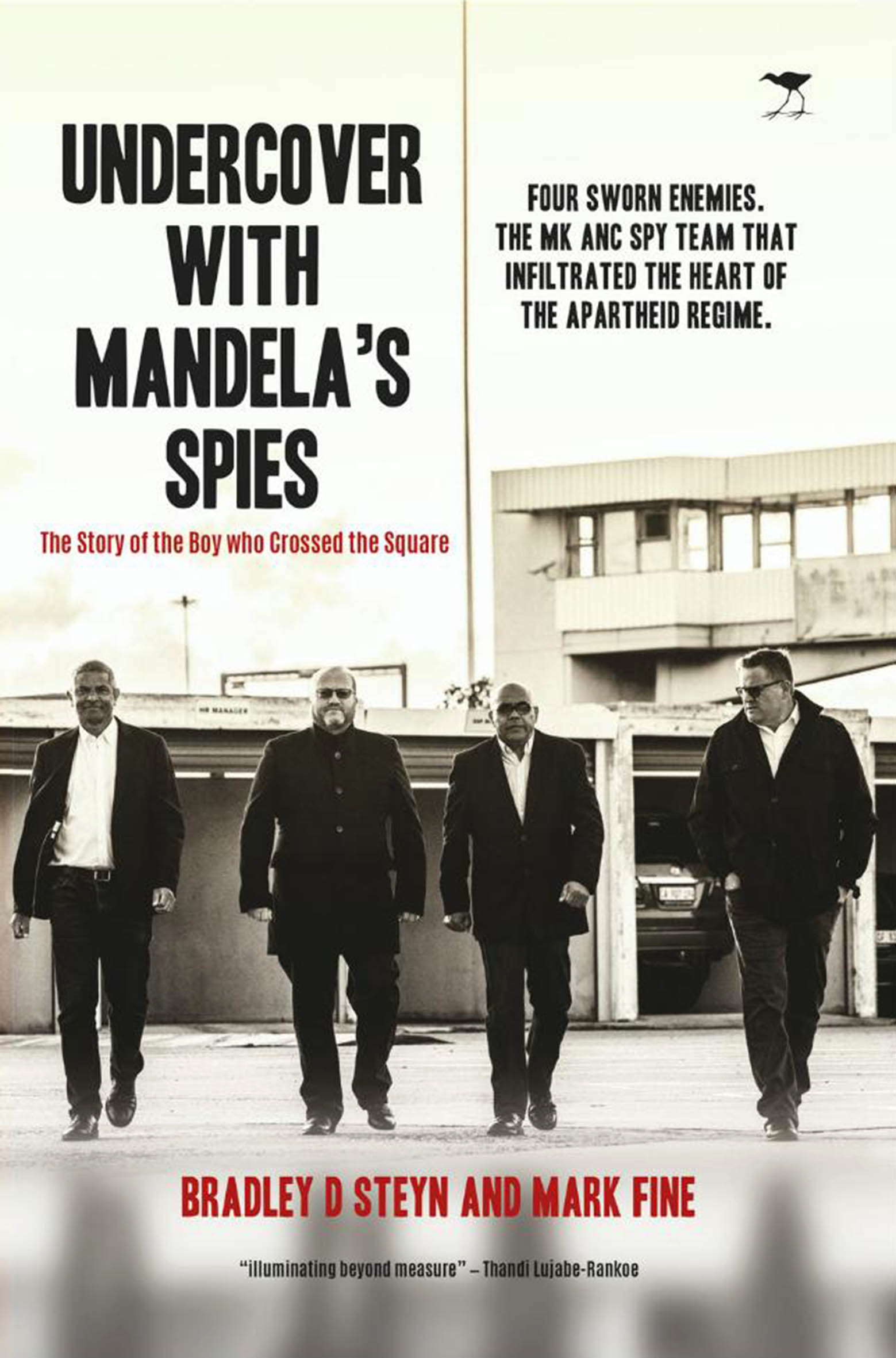

Undercover with Mandelas Spies (Jacana)

Bradley Steyn worked for the apartheid security police, but was recruited to Umkhonto weSizwe and infiltrated right-wing conspiracies. He worked with novelist Mark Fine to turn his story into a book, Undercover with Mandela’s Spies (Jacana). This is an edited extract, telling of one frightening operation

We slowed to a crawl as we squeezed between a house and a burnt-out taxi and then came to a stop in an alley behind the small home.

I instructed my team to secure the perimeter. Inside the house was a large man who I’ll dub “Mr Panic”. I asked him to take a seat at the dining table as we needed to go over a few points. Mr Panic pulled up a chair, sat for 40 seconds, then bopped up again. That wasn’t working for me. I needed him to focus. I swear, if the Major hadn’t been around, I’d have handcuffed the oke to the table. Instead, I grabbed his hand and touched his clammy palm. It was time for my special talk.

“You’re really frightened, I know … That’s perfectly normal.” It was important to acknowledge his fear. “I get it. Combat isn’t your thing, but remember fear is your key to survival. That’s where your flight-or-fight instinct comes from. So get ready to use it.”

But my motivational speech had fallen on deaf ears; Mr Panic only had eyes for his shoes. “Don’t look down … Look at me! Now look at that man over there,” I said, pointing to Neil. “Listen only to that operator and me. We are your best chance to stay alive.”

My “second” swept the house to see who else was there. Then I made sure all team members could identify the client. Over the next several minutes, they dropped by, one at a time, to see the man they were charged to protect. We couldn’t have one of our guys take out Mr Panic by mistake.

“You have any firearms in the house?” I asked. “Promise I’ll give it back when you need it.” Mr Panic pulled a .38 Special from the belt supporting his bulging belly, and as soon as he no longer held the weapon as a pacifier, the shakes began. The poor guy was terrified.

All the while the landline had been ringing. It persisted, loud and shrill. Probably someone belatedly sounding the alarm. I disconnected the ringer. Peace at last.

But our location was way too vulnerable. We needed to move before a grenade or petrol bomb hit the place. I ordered us out of there and planned to relocate to a safe house in Paarl, about 45 minutes away.

But Mr Panic had other ideas. He wanted to bring his daughter with him. I explained that we had to secure him first, and then I’d send guys to bring her in. But Mr Panic flipped. “No. No! She’ll only come with me.” In the end, I agreed.

Outside, Mr Panic’s crew had hitched themselves to our convoy. They did not amount to much of a threat to potential attackers because their arsenal consisted of no more than two firearms and a cricket bat. This was only getting better. I walked over and introduced myself with a friendly warning: “If I see any of you point a gun in my direction, I will shoot you.” That broke the ice.

We ripped the South African Black Taxi Association decals off three of Mr Panic’s vehicles and loaded up. Three men took one, while Neil de Beer, Mr Panic and I followed in another. Mr Panic’s boys were bringing up the rear in the third. The Major had left us earlier to go on a logistics run. We needed lots of ammunition, including potent 7.62mm cartridges to feed into our R5 machine guns.

It was almost nine by the time we reached the underpass to the Golden Acre mall. Then … Crack! Crack! We were taking gunfire in the confined quarters of the van.

“Fuck!” Neil shouted. “No, man!”

Blood splattered the inside of the passenger window. It continued to squirt out of the driver’s neck as our vehicle slowed. The bullet had severed tissue, tendons, veins and axons, the thread-like nerve fibres that transmitted impulses from cell to cell within his body. With the signal to his brain lost, our driver’s foot drifted off the accelerator and the taxi ground to a stop.

I had challenges of my own. I couldn’t see as the blood spray had covered my Raybans. I wiped them with my sleeved forearm. Then Neil’s large frame flew over the seat and landed on top of me, “Sorry, Boet, we need to move.”

I grabbed Mr Panic and, pushing his head down, steered him to the rear of the taxi. Mr Panic was now Mr Obedient and taking instructions well. I kicked out the back window. On our haunches, hidden by the van’s chassis, I saw that we were no longer receiving contact on our left flank. No such luck on the other side, though. Fully automatic firearms were ripping into us. I pushed forward and tucked him behind the densest part of the vehicle, the engine block. And then came an additional worry. Where was that fucking R5? I couldn’t find it, which meant it was me and my 9mm against the fully automatic machine gun that was clapping and echoing off the walls around us.

But any of this would only be a fleeting solution; I smelled leaking petrol, and so did Mr Panic.

“We have to get the fuck out of here!” he screamed, as he bolted directly towards the war zone. A quick sweep of my leg ankle-tapped Mr Panic and brought him heavily to ground. Only thing, he was now out in the open.

Neil laid suppressive fire from behind the van’s wheel well as I crawled forward. I grabbed Mr Panic by the collar to drag him to safety, but he was now bawling. Each time I yanked, he cried louder, bringing unwanted attention. Bullets began stitching their way toward us.

I had to slap him, hard, across the face, to try to centre the oke. We then took shelter back behind the van, which was now pock-marked with bullets. With my left knee pinned between Mr Panic’s shoulder blades to prevent him attempting another mad dash, I started to lay down fire and managed to get off a few more 9mm rounds without losing my face.

Sirens. The police were closing in.

The rival taxi gang panicked; they started yelling among themselves and then clambered into a vehicle with a Congress for Democratic Taxi Associations decal and sped off.

Neil joined me, and we bundled Mr Panic into the lead taxi. Neil then headed off to the safe house in Paarl and, armed with a father’s anxious note, Mr Panic’s crew set off to fetch the taxi honcho’s daughter.

My attention was now focused on the wounded driver. He had lost a great deal of blood. I carefully lifted him into the rear of the vehicle and made him as comfortable as possible. That done, I took over driving duties and headed for the highway. My destination was a friendly veterinarian who had done a mandatory two years’ medical internship before he realised animals were preferable to people as patients.

He was a useful chap. He assured me the driver could be sufficiently stabilised to give us time to get him real medical care. Nor did the vet flinch when I asked him to manipulate the wound to look more like a knife stab. Later that night we transferred the driver across to the naval base at Saldanha. The doctors never questioned the nature of the driver’s wounds, although they took his condition seriously. I left after military doctors topped our man up with blood and antibiotics. Then it was time for the clean-up.

The shot-up taxis suffered a different fate. I took them to a scrapyard in Atlantis, a manufacturing town created using a complicated scheme of relocation tax credits that collapsed the moment the incentive programme ended.

The scrapyard owner had survived the economic bust because he’d decentralised his business activities and had a side hustle as a dagga dealer. He was the silent type who liked to do favours for the SB (Security Branch). Sometimes he’d even melt down gold into generic ingots when Andy chose to pay us with gold instead of cash.

Eventually, I headed home to my place in Fish Hoek and stripped off my blood-soaked clothes, wrapped them in a plastic rubbish bag and headed for the shower. As I washed my face and hands, I noticed that the fingers on my left hand were still stuck together with blood. I was immediately overcome by the same feeling I had had as a 17-year-old, in the shower after Strijdom Square. My heart started to race. But I had to shake that off because that’s also when I realised I had been shot.

The bullet had pierced the inside of my left bicep. Only three centimetres from my heart as my arm lay vertically at my side. The moment my brain registered what had happened, the pain kicked in. I kept splashing cold water on the wound, trying to cool it down, but the hurt would not subside.

I called “Zoë”, the woman we worked with at our pager company, and had her forward a message to Neil: I’m alive. Assistance needed.