(Oupa Nkosi/M&G)

Long-standing feuds between adults are playing out at schools, with the violence forcing them to be closed for long periods. Bongekile Macupe and Oupa Nkosi went to Sahlumbe in KwaZulu-Natal to see the effect on one high school

Nontobeko Sibiya speaks of the fights between learners at Sahlumbe High School in an animated way. But it is not a laughing matter.

Sibiya is a hawker at the school and what she describes is like something out of an action movie: boys pelt each other with stones while girls scream and cheer them on; teachers speed out of the schoolyard in their cars to prevent them being damaged; security guards duck the stones also thrown at them. There have been stabbings and one learner had a gun.

Costly business: Hawker Nontobeko Sibiya didn’t earn any money in the months that Sahlumbe High School was closed. (Oupa Nkosi/M&G)

Costly business: Hawker Nontobeko Sibiya didn’t earn any money in the months that Sahlumbe High School was closed. (Oupa Nkosi/M&G)

This kind of scene has become the norm at the school in Sahlumbe village, about 20km from Weenen in KwaZulu-Natal, since last year. The conflict intensified in April this year, forcing parents in the area — who fall under Inkosi Sphamandla Mthembu, of the abaThembu, in the ebaThenjini Tribal Authority — to close the school for three months in an attempt to try to resolve the issues that had caused the fights.

The mid-year exams were not written. The KwaZulu-Natal department of education says it spent R3-million on a three-week camp in June for matrics while the school was closed — other grades simply lost out on schooling. A similar shutdown happened last year, because of the fights.

The mountains tower over the area that includes the giant Thukela River. They give a constant sense of Sahlumbe having limits. The only way in and out is on dirt roads that run adjacent to the river. A bridge connects people to their farms, their crops fed with water from the river. But when the Mail & Guardian visits there isn’t much water in people’s taps, nor has there been for several days.

Protesting this failure in service provision, people have blocked several roads, including that to Ladysmith, the nearest large town. Teachers living there, who usually do the hour-long commute, were unable to get past the rubble. So, although Sahlumbe High School reopened last month, at the start of the third term, it has been operating on skeleton staff.

Driving to the school, the M&G meets two children from the nearby primary school. No older than 10, they are patching potholes in the dirt road in return for money. There are no teachers to keep them in class.

The service delivery problems mix with, and exacerbate, the violence that keeps shutting down the high school. Parents blame dagga, girls and overcrowding as some of the factors that have led to these fights among boys at the school. They also fight because of impi yezigodi (faction fights) occurring elsewhere and playing out on the school grounds. This phenomenon has become increasingly common in schools across the province.

Mthembu’s brother, Sicebi Mvelase, says there are no faction fights in Sahlumbe village. The boys, he says, fight over various issues and turn them into faction fights based on where they come from.

The fight that led to the school being closed for three months this year was between boys from eNkasini and eManseleni villages, who were fighting over a girl. Last year, the fight was between learners from eManseleni and KwaNomoya and it was also over a girl.

Mvelase says impi yezigodi is a reality in most villages in KwaZulu-Natal. Instead of sitting down to resolve issues people fight and children use the same approach on school grounds. “When we have disagreements we take out guns and shoot each other,” he says.

These faction fights have been taking place in the villages near Sahlumbe for years, according to people the M&G talked to.

The fights have, according to the provincial department of community safety, claimed 39 lives since last year. The most recent deaths were in June, when two women and a child were killed in their home while they were sleeping.

A fight between the people living in Nhlawe and KwaMadondo, about 20km from Sahlumbe, has prompted men to sleep in the surrounding mountains for fear of being killed while sleeping in their homes. That fight has spilled over to Weenen Combined School, the next school down from Sahlumbe.

After Sahlumbe High School was shut down, five meetings led by Mthembu were held to get to the root of the problems at the school and to find lasting solutions. The learners were also called to the meetings to explain themselves. Sixteen boys were identified as the culprits and were expelled. Mvelase says parents agreed that if a child is found to be misbehaving they must be expelled to bring peace to the school.

The spokesperson for the provincial department of education, Muzi Mhlambi, says these fights at schools are “unfortunately are out of our control. It is a pity that these fights start in communities and at times involve adults and spill over to the youth in the community who happen to be our learners and unfortunately school is where all of them converge.”

He says there is little that the department can do to avert these fights and what’s needed is for everyone involved to find solutions.

Trouble: Sicebi Mvelase, the chief of Sahlumbe village and brother of Inkosi Sphamandla Mthembu, says faction fights are a reality in the area. (Oupa Nkosi/M&G)

Trouble: Sicebi Mvelase, the chief of Sahlumbe village and brother of Inkosi Sphamandla Mthembu, says faction fights are a reality in the area. (Oupa Nkosi/M&G)

The chairperson of the school governing body, Siyabonga Mbatha, says the fights were so bad that teachers feared for their safety. He says that things deteriorated to such an extent that one of the interventions by Mthembu last year was to ask chiefs to nominate men to enforce discipline at the school. Five men were then stationed at the school to assist the two security guards working there.

Mbatha says: “But those boys still used to fight even in the presence of those men. They would throw stones at each other, stab each other and we also found a gun on one of the boys last year. Things have really been bad here.”

Sibiya, who has been a hawker at the school for six years, says she still fears for her safety at the school but, because she needs the money, she has no choice but to still work there. “Into yayila esikolweni ngiyayesaba. I thought we would never come back to this school. When they were throwing stones at each other you could not control them.

“They hit the container I used to put my money in with their stones and my phone was also there. My money spilled to the ground and I could not recover it because there was chaos. I was also running for my safety.” Sibiya says that when the school was closed she did not get an income. The money she makes there supplements the child social grant she gets and enables her to support her children.

She anticipates a gloomy Christmas because she was unable to pay into her stokvels.

She usually uses the stokvel money to buy clothes for her children in December, and to afford the costs that come with the December holidays.

Since the school reopened last month, she says there has been peace and the learners seem disciplined.

That is one small step. With teachers unable to get to class, the grades that didn’t get catch-up classes will continue to fall behind. And the school buildings are inadequate.

Schoolchildren attending Weenen Combined School, which has also been affected by schoolyard fights, either walk home or catch the local bus.

Schoolchildren attending Weenen Combined School, which has also been affected by schoolyard fights, either walk home or catch the local bus.

Built by the Sahlumbe community 37 years ago, the education department has since added two office blocks and a block of classrooms and provided several mobile classrooms. But even this is not enough because the school services eight villages. Last year, 1 283 learners attended the school — slightly higher than this year’s enrolment of 1 255.

Mbatha believes that overcrowding has contributed to the unruly behaviour of learners, because teachers battle to control the large classes. The chair of the school governing body adds that last year up to 80 children were crammed into some classrooms.

He says that, at the meetings held after the school was shut down, learners said some teachers appeared not be committed to their jobs and left them unattended in classrooms. This led to them getting into petty fights that would later explode.

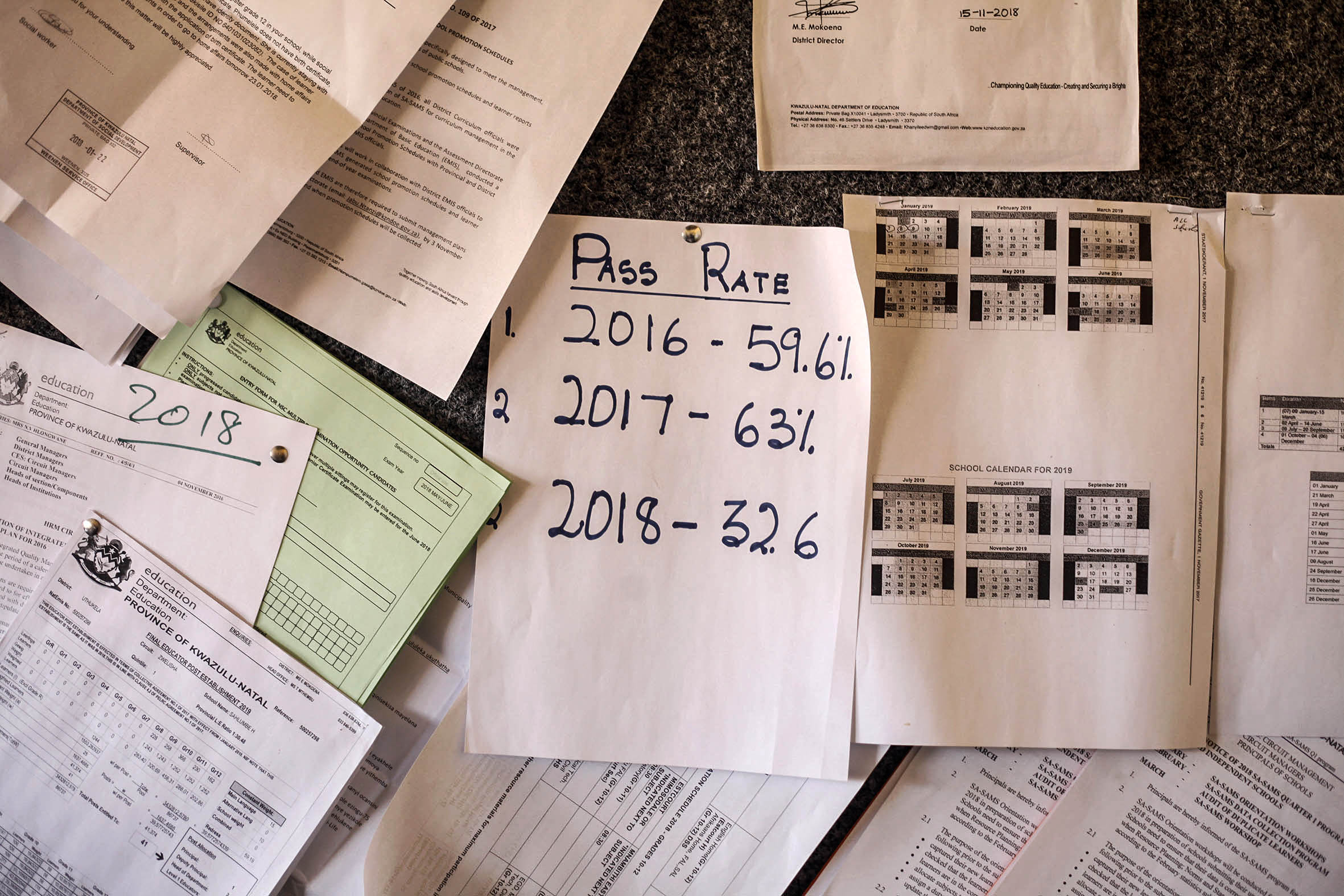

Mbatha says the overcrowding and the fights have led to a decline in the matric pass rate.

Sahlumbe High School went from a school that used to get merit awards for its pass rate — it obtained a 96.3% pass rate in 2002 but a dismal 32.6% pass rate last year.

Sahlumbe High School had a matric pass rate of 96.3% in 2002 but it steadily declined to 32.6% in 2018. (Oupa Nkosi/M&G)

Sahlumbe High School had a matric pass rate of 96.3% in 2002 but it steadily declined to 32.6% in 2018. (Oupa Nkosi/M&G)

A new high school will be built in the village next year. This, it is hoped, will be a step towards taking away one of the pressures that drives learners to use the school grounds as a battlefield.

But people are still worried. One parent says: “For now we are just holding our breaths because they have not started their fights, mhlawumbe kuzolunga, we are not sure.”

Learners die in impi yezigodi

In 2011 and 2012, Isolezwe newspaper reported that faction fights in schools in the Empangeni area were rife.

In 2011, impi yezigodi in eSitheku High School resulted in some learners not going to school for fear of being killed or beaten up. And exams were not written. In 2012, at Mkhombisi High School, children also stopped going to school as a result of fights between learners. In 2015, Isolezwe reported that a learner was killed at Phiwamandla High School, about 40km from Mtubatuba. During the fight between two factions the schoolboy was stabbed.

In November 2017, the North Coast Courier reported that a fight between schoolboys from different villages in Mandeni had led to exams for grade eight and 11 learners being suspended at Mbuyiselelo High School. Ilanga reported that the situation was so bad that police had to take some learners to school and that they were under police guard when they wrote exams. Others stopped going to school because they feared being assaulted.

In 2018, the Daily News reported that two schoolchildren were killed at Masakhaneni High School in KwaMakhutha, near Amanzimtoti.

And, last month, a learner at Thandaza High School in Mpumalanga township, near Cato Ridge, was killed at school, also in an alleged factional fight.