(John McCann/M&G)

‘I get the money: What will I do with it? I cannot walk five metres without losing breath. I cannot even go to the shop, it is ridiculous, but that is the way it is,” said silicosis sufferer Gabriel Bester, who sounded surprisingly upbeat, in a telephonic interview with the Mail & Guardian.

Bester, 69, contracted silicosis in 1988 after working for 17 years at the Harmony Gold mine in the Free State as a mine overseer.

He says when he found out 31 years ago that he had the disease but, because he was only 38 years old, he did not think about it much. This changed as he grew older and his health started getting worse. Then, 15 years ago, he contracted tuberculosis.

Bester is a beneficiary of the lengthy class action begun in 2012. A R5-billion settlement was this week handed down by the high court in Johannesburg.

The case was brought by Richard Spoor Attorneys, law firm Abrahams Kiewitz and the Legal Resource Centre on behalf of 59-year-old former mine worker Bongani Nkala and 69 other class representatives (a total of 25 000 miners) against mining companies, among them African Rainbow Minerals, Anglo American South Africa, AngloGold Ashanti, Gold Fields, Harmony Gold and Sibanye-Stillwater.

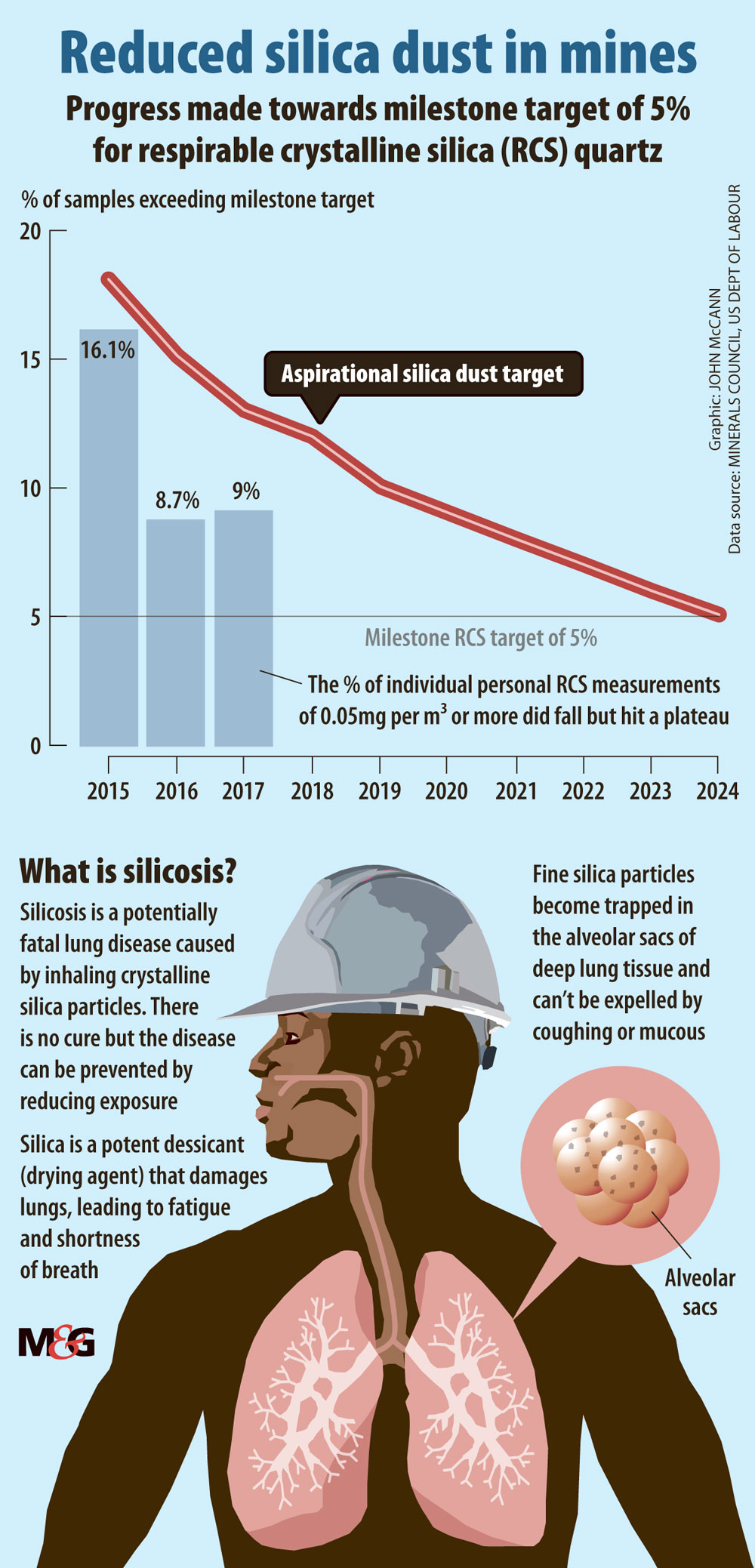

But the industry is far from free of the threat of silicosis. The latest data from Minerals Council South Africa’s integrated annul review shows that, for 2017, miners’ personal silica measurements were at 9%, down from 16.1% in 2015.

The industry has a target of reducing exposure to silica dust to 5% by 2024.

Industry sources said exposure did not necessarily mean a person would contract silicosis, but managing the dust would minimise the chances of workers contracting the disease.

Silicosis is an incurable lung disease that results from people breathing in dust containing silica. It builds up in their lungs and breathing passages, leading to scarring and making it difficult to breathing.

Affected miners will get amounts ranging from R10 000 to R500 000, depending on the severity of the disease. Bester, who now lives in the Western Cape and was one of the miners represented by Richard Spoor Attorneys, says: “How do you compensate for the quality of life I am living at the moment? I cannot move for five metres without losing breath; I cannot shower without having oxygen. I get out of breath if I get excited or if I talk too much.”

But, even given the state he is in, he says the money is reasonable. “At least something is coming to my side, which I think is fair.”

The M&G also spoke to Malungisa Thole, who lives in Bizana in the Eastern Cape. The area, says George Kahn, who is part of Richard Spoor’s legal team, is a major source of migrant labour in South Africa.

Thole says he found out he had silicosis in 2005 after suffering from a severe coughs. He worked at the Western Areas Gold Mine, to the west of Johannesburg, from 1980 to 1999. “We feel good that we have won the case because white people have mistreated us for very long,” Thole said. “So you get retrenched at work while you were earning peanuts and even with the blue card money [Unemployment Insurance Fund], after three months it’s finished.”

Thole says he plans to send his two children to school with the money from the settlement.

Bester and Thole are able to put the compensation money to good use, but many miners have died from the disease. Lawyers said 4% — about 1 000 — of their clients died each year.

Spoor told the high court earlier this year that, if the settlement was not reached soon, “over the course of the litigation the class members would likely continue to die at the rate of 4% per annum. The result of litigating the action would, therefore, be not only to delay justice for many of the class members but also deprive those who die before damages are paid of any modicum of justice.”

Kahn cautions that the number of deaths could be higher: “This does not reflect the actual number of expected deaths since the true population size is unknown and possibly dynamic as new miners are diagnosed as previous silicosis miners pass away.

“It ranges widely in the research, with top end numbers estimated somewhere around 500 000 miners living with silicosis based on autopsy research conducted by Jill Murray, honorary associate professor at the Wits School of Public Health.

Khan said: “The lower end estimated numbers are several factors lower, in the tens of thousands.”

Tshegofatso Mathe is an Adamela Trust business reporter at the Mail & Guardian