In addition to the comics, the exhibition highlights the use of comic-making tools and how they have lived in other, more revered, art forms. (Paul Botes)

“We tend to model ourselves around certain European institutions but you find that even those institutions are having an identity crisis because they are having to re-evaluate what it means to be a modern and contemporary art museum in this current environment.” — Khwezi Gule in the Mail & Guardian shortly after his 2018 appointment as Johannesburg Art Gallery’s chief curator.

Commercial art spaces are not obliged to serve the public. They are privately owned and tasked with the mission to keep their artists visible while selling art. This is not the case for a public institution such as the Johannesburg Art Gallery, next to Joubert Park, where serving the public is a must.

But there are many publics and they have different interests and needs for the gallery’s space. Whether it is the seasoned art crowd, the contemporary scholars, those who attend openings for free wine, the busload of schoolchildren from across town, tourists or those who come by every day, it is important that such an institution continues to cultivate a museum-going culture.

One of the ways is through the Johannesburg Art Gallery’s current exhibition, The Art of Comics.

The Mail & Guardian spoke to one of its curators, Tara Weber, about fulfilling the museum’s function from a curatorial perspective.

Weber has been working at the gallery for five years where she played a role in curating past shows, including The Evidence of Things Not Seen (2016) and Spellbinders (2017). Her curatorial work looks to create new narratives for the museum. The Art of Comics, which is on until November 18, is her first project as lead curator.

In Weber’s hands, the exhibition seeks to encourage a public that is “not familiar or feels intimidated” by gallery spaces to use the exhibition as a trial run because “comics are a more democratic means of expression”.

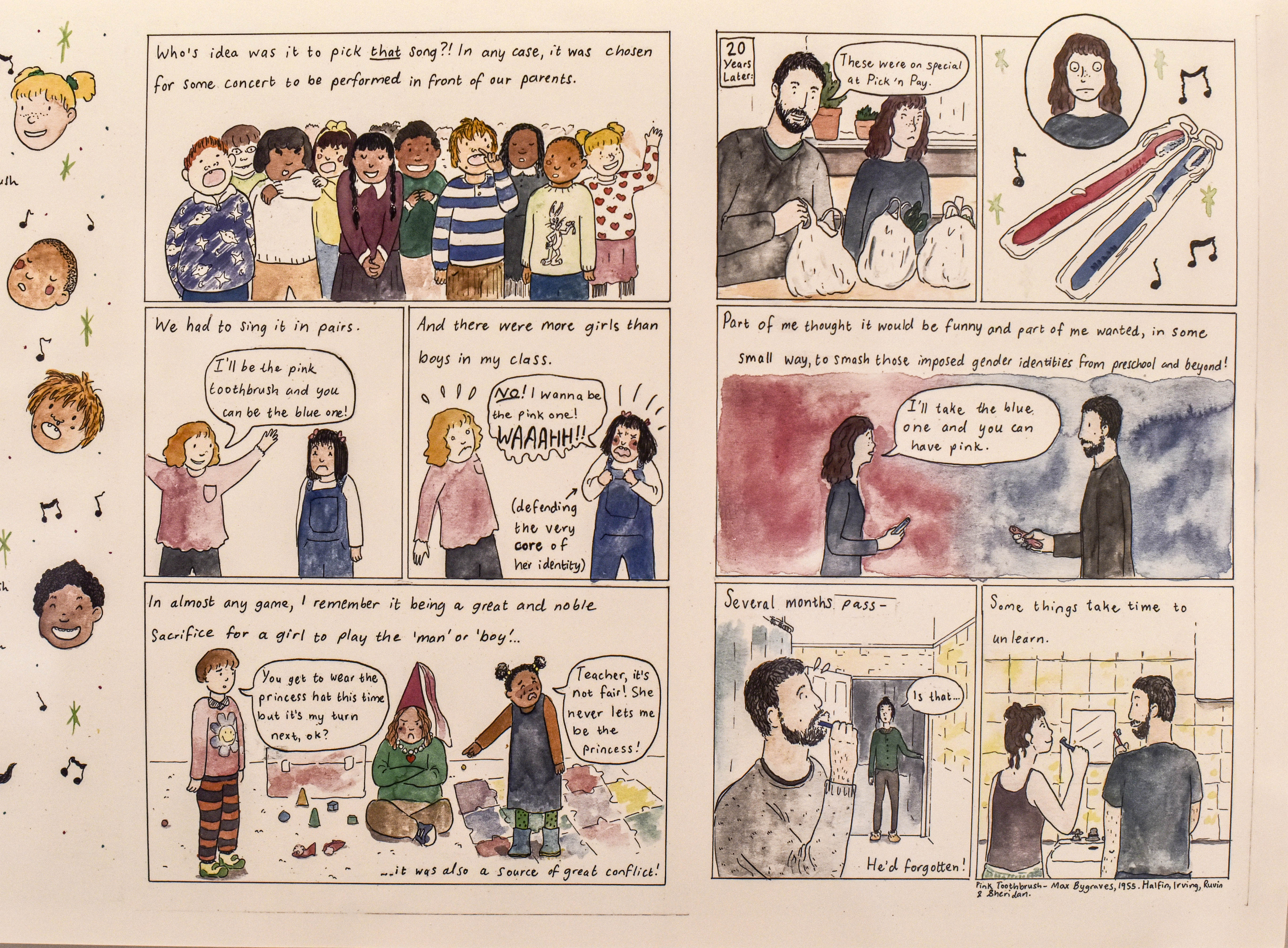

Like fine-art forms, the work featured in the exhibition explores themes such as contemporary history, folklore, politics, science fiction, augmented reality and identity. It expands the “political packaging”, as portrayed by the likes of “Zapiro, Madam & Eve and Treknet”, that Weber says comics are often presented in.

As a result of the gallery’s relationship with the French Institute of South Africa, the exhibition features South African comics and French bandes dessinées in conversation with one another.

Together with Weber, the exhibition is curated by Raymond Whitcher and Thierry Groensteen. Whitcher is a PhD candidate at the University of the Witwatersrand, where he lectures on animation in the digital division of the university’s arts department. Groensteen is a bande dessinée scholar. In 1984 he was the editor-in-chief of Schtroumpf: Les Cahiers de la Bande Dessinée, one of the first publications to intellectualise comics. Groensteen now lectures at the European School of Visual Arts. He curated the Francophone region of The Art of Comics.

Walking about the exhibition

The public’s introduction to the exhibition is a selection of pieces from the museum’s art collection. They set a tone that is as comical as it is serious. To do this the Phillips Gallery at the entrance highlights the use of comic-making tools and how they have lived in other, more revered, art forms. These tools include caricature, the use of panels to depict different scenes, imaginary worlds and the use of text on images. Some of the pieces include Johannes Maswanganyi’s sculpture of apartheid president PW Botha (1998), the Passion Jesus linocut by Azaria Mbatha (1962), Tito Zungu’s mohair tapestry (1994) and a Roy Lichtenstein pop art movement piece titled Crak! (1964).

The museum’s west wing features more than 25 works from South African artists including Mogorosi Motshumi, Joe Daly, Loyiso Mkize, Nas Hoosen, Daniel Clarke, Daniël Hugo, Kit Beukes, Jesse Breytenbach and Kay Carmichael. Mkize is the artist behind African superhero Kwezi. Motshumi is the creator of 1980 comic strip Sloppy and author of The Initiation, the first autobiography in the format of a graphic novel by a black South African.

The eastern wing has a similar number of works by artists from France, Belgium, Switzerland and the Reunion Islands. The Francophone artists include Charlie Hebdo, Pénélope Bagieu and Lewis Trondheim. Hebdo wrote The Secret Life of Teenagers. Bagieu founded the illustrated blog My Life is Fascinating. And Trondheim is the founder of the independent bande dessinée publishing house L’association.

To elevate the medium and give it its due diligence, the curators made use of two interventions. First the museum levelled the playing field by ensuring that all the works are high quality reproductions printed on high quality archival paper. They were then float-framed to give them the same aesthetic treatment that other mediums would be given.

The comics are in a variety of drawing styles including rough sketching, doodling, caricature, Manga, realism and pointillism. These drawings are in a variety of mediums including woodcutting, etchings, pencil, charcoal, lithography, watercolour, acrylics and gouache.

Although there’s diversity in form, the exhibition lacks variety in the artists represented.

Weber explains how the selection process did not involve a call for artists to exhibit their work. Instead, the curators did their research and approached artists who were making visible waves in the genre of comics. “The comic sphere in South Africa is still dominated by white men,” says Weber, adding that even though there are amazing womxn in the industry, “it can be difficult to find them because they haven’t been given a platform”. And although Weber says she would have “liked to include” other artists, “time constraints” meant that the exhibition’s west wing only represents South Africa’s comic landscape. This is with the exception of the storytellers from Zimbabwe, Kenya and Botswana, who collaborated with South African illustrators to create the graphic novel Meanwhile …

Staying for the art

The Art of Comics exhibition comes at a time when private museums and institutions such as the Javett Art Centre at the University of Pretoria are gaining prominence. According to Weber, this is an opportunity for public museums such as the Johannesburg Art Gallery to rethink their role and function.

Before the artistic function of a museum can be considered, Weber says she has realised how important it is not to “dismiss the practical functions of a museum”. Some of the functions include it being a quiet and safe haven amid the bustle of Joubert Park, a public but private place to meet someone for the first time, or a space where schoolchildren wait for their parents to finish work after school. “These are all valid uses of a public museum,” says Weber, who has now tasked herself with ensuring that patrons who do not come for the art now “stay for the art”.

To encourage interaction with the art, the curators considered the scale of the works. Most of the work featured in the exhibition is in the same size that the artist would publish in a book. Unlike the displays at conventional exhibitions, the small scale here beckons visitors to get close to the work so they can make out the images and read the text. The close proximity works to increase patrons’ confidence to interrogate the details that make a work of art.

The exhibition is also fitted with a life-size chalkboard where children are welcome to draw their own characters. The museum decided to include such interventions to dispel the top-down interaction that many may associate with museum spaces. This goes hand-in-hand with the exhibition’s interactive brochure. In addition to having information on the art works, the brochure includes an extensive glossary about comics, a guide and empty squares for visitors to make their own comic, as well as an opportunity to colour an existing animation. The artworks have also been selected to complement what is being taught in high school fine art and design classes.

The Johannesburg Art Gallery has also partnered with the South African embassy in France, the French Institute of South Africa and Total to organise workshops about making comics, visual storytelling, animation and augmented reality. This will run alongside a film festival where animated films and others about comic making will be screened at The Bioscope at 286 Fox Street on Sundays for the duration of The Art of Comics exhibition.

At the end of the impromptu walkabout with Weber, we sit on a bench in the Johannesburg Art Gallery’s courtyard, observing Joubert Park’s endless hoots and hollers. “This notion of a museum being the kind of place where you can’t touch anything and you have to be quiet, I just don’t know if that works anymore,” says Weber. “I don’t know who that’s serving but it’s not serving Joubert Park.”