Rights: Florence Sosiba, president of the South African Domestic Service and Allied Workers Union. (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

‘Anything can happen,” says domestic worker Florence Sosiba. “I am sitting here in the house. A criminal can come. I am the victim. My boss is not here. I can die for his house.

“But if I am not in the Coida [Compensation for Occupational Injuries and Diseases Act], how will my family get something?” asks the recently-elected president of South African Domestic Service and Allied Workers Union (Sadsawu).

The Act compensates workers or their survivors for work-related injuries, illnesses and death, but the more than one million domestic workers are not covered by this legislation.

Now, after years of fighting, domestic workers are one step closer to being included in the Act. But, if they are not organised, these efforts could be for naught.

Sosiba sits on a couch in her employer’s grand Johannesburg home. The lounge looks out on to the swimming pool, a common feature in the suburb of Fairland. The dull buzz of the lawnmower filters in from outside.

Sosiba has been a domestic worker for 36 years. She says working in a private household means there is no one to ensure that labour laws are being complied with.

“You can be abused. You can be undermined. You can work long hours … You work hard and you don’t get the benefits,” she says, beads of sweat gathering on her forehead and nose.

It also means, Sosiba says, that if a domestic worker is disabled or dies on the job they and their family members are left without a safety net.

“I’m scared that maybe I die — like [Maria] Mahlangu, falling in the pool. There are a lot of cases like this, a lot of them,” she says.

Mahlangu’s death in 2012 sparked a seven-year battle to challenge the exclusion of domestic workers from the Act. She drowned in her employer’s swimming pool, but her family received no compensation for her death.

In May, the high court in Pretoria handed down an order declaring the exclusion of domestic workers from the Act unconstitutional and invalid.

In October, the court further ruled that the declaration of invalidity must be applied retrospectively to provide relief to other domestic workers who were injured or died at work prior to the granting of the order.

Last week, the Socio-Economic Rights Institute of South Africa, on behalf of Mahlangu’s daughter, Sylvia, filed an application in the Constitutional Court to confirm the high court order.

But the leaders of domestic worker organisation say there is yet another hurdle ahead of them: organising and educating domestic workers about their right to claim compensation.

Sosiba says she has learned a lot about her rights through her involvement in Sadsawu. But it is difficult to get domestic workers to join unions. “It is difficult, because I am working here alone. Next door, she is working there alone. It is not easy to organise. We try, but it is not easy.”

Sosiba is concerned that too few domestic workers know the ins and outs of the Act and will be left behind even when they are finally covered. “We must mobilise ourselves. We can’t tell our members to go to a march before we educate them. We must sit down and have workshops and tell them what it means to be included in Coida.”

A member of fledgling union the United Domestic Workers of South Africa (Udwosa), Emma Mthimunye, says she would know “nothing” without the efforts of the union. “We learn there. We must know our rights. When we don’t know our rights, employers can do whatever they want to us,” she says.

Mthimunye, who has been a domestic worker for 14 years, says many in her line of work are afraid to join unions because they fear being fired.

“But we have to talk,” she says. “Some of our employers, they know that they must pay us. They know that they must register us. But because we are afraid to talk, things just stay the same.”

Fear factor: United Domestic Workers of South Africa member Emma Mthimunye says workers and employers must know their rights and obligations. (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

Fear factor: United Domestic Workers of South Africa member Emma Mthimunye says workers and employers must know their rights and obligations. (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

Pinky Mashiane, the founder of Udwosa, is under no illusion about the trials ahead of domestic worker organisers.

She says the difficulty of mobilising domestic workers is paired with the problem posed by also having to ensure their families are educated about their rights.

“Others don’t have the information that we have about Coida. Many domestic workers don’t know anything about Coida, and they have been in the line of duty,” she says.

“When it comes to those that have died, their families have lost their breadwinners and parents. How are we going to find all of them?”

The other difficulty will be ensuring that there are records of worker injuries or deaths that occurred before the high court order regarding the Act, Mashiane says.

It is also necessary to make sure employers are on board. According to the Act, employers must register with and pay yearly contributions to the Compensation Fund.

“The compensation commissioner must go to the employers and sit them down,” Mashiane says. “They must reach out to the employers and tell them to register.”

There is also the question of money. With few paid-up members, domestic worker unions barely collect enough subscriptions to stay afloat. In 2011, Sadsawu was on the brink of deregistration, but was saved by its labour federation, Cosatu, and outside funders. At the time it had only 1 500 paid up members.

Sadsawu deputy general secretary Eunice Dhladhla said the union still relies on outside funding.

For Udwosa, money is even tighter.

Mashiane still works part-time as a domestic worker and as a porter at a hospital. The money she makes goes towards travelling around the country to organise domestic workers.

“If there was money, every weekend I would be going to find domestic workers to tell them about Coida,” she says. “I try to reach them with the little that I get, but there is no money.”

New rules ‘won’t causejob losses’

There is little data to suggest that further regulation of domestic work in South Africa will result in large-scale job losses.

Late last year, the sectoral determination for domestic workers was adjusted so they would earn a minimum hourly rate of between R12.47 and R16. Shortly after this, the National Minimum Wage Act, which came into effect in January, set the wage floor for domestic work at R15 an hour.

According to data from Statistics South Africa’s most recent quarterly labour survey, immediately after these increases were enacted, there was a drop in the number of private household workers. But in the last quarter, this number started to recover, increasing by 35 000.

The number of private household workers now stands at 1 286 000. Private household workers include domestic workers, gardeners, cooks, butlers, drivers and caretakers. More than 77% of these workers are women.

There are 20 000 more private household workers than there were a year ago and 32 000 more than there were 10 years ago.

Detractors of the minimum wage warned that it would spark job losses. A similar argument was made in 2002, when the government set the first sectoral determination for domestic workers in an effort to protect vulnerable workers from exploitation.

A 2012 study seemingly backed this up, pointing out that in September 2000, there were more than one million domestic workers in South Africa. This figure dropped to 977 000 in September 2003 after the sectoral determination was enacted.

Hard road ahead: United Domestic Workers of SA founder Pinky Mashiane. (Oupa Nkosi/M&G)

Hard road ahead: United Domestic Workers of SA founder Pinky Mashiane. (Oupa Nkosi/M&G)

But a 2016 paper by labour researcher Debbie Budlender notes that analysis by several researchers since 2002 “has found little or no evidence of any decrease in employment as a result of the introduction of the sectoral determination”.

The number of domestic workers in the country has hovered at about 1.3-million during the last 10 years.

Fairuz Mullagee, a researcher and co-ordinator of the Social Law Project at the University of the Western Cape, said that when regulation changes are introduced “there’s quite a lot of scare-mongering … and parties hide behind their concern about job losses”.

She said: “Domestic workers are an integral part of the economy. They make it

possible for millions of people to go to work every day. They take care of over a million private homes and add great value to the economy.”

A 2013 study by the International Labour Organisation showed that 90% of domestic workers around the world were not covered by the same laws as workers in other sectors.

Mullagee said new regulations are not a threat to jobs for domestic workers. “But I think there needs to be a complete shift in the way in which precarious workers are regulated. And there needs to be more state intervention.

“Employers need to be made aware of the value of domestic workers and need to understand that, like all other workers, domestic workers have rights.”

Compensation Fund is too broke, fears department

The beleaguered Compensation Fund may have to be overhauled to handle claims by domestic workers and their families once they are covered by the Compensation for Occupational Injuries and Diseases Act.

According to the senior attorney for the Socio-Economic Rights Institute of South Africa (Seri), Thulani Nkosi, the department of labour has said the fund will be left bankrupt if the Act — which compensates workers, or their survivors, for work-related injuries, illnesses or death — is applied retrospectively to domestic workers.

Seri represented the daughter of Maria Mahlangu, a domestic worker who in 2012 drowned in her employer’s swimming pool. In May the high court in Pretoria handed down an order declaring the exclusion of domestic workers from the Act unconstitutional and invalid. In October, it further ruled that the declaration of invalidity must be applied retrospectively to provide relief to other domestic workers who were injured or died at work prior to the granting of the order.

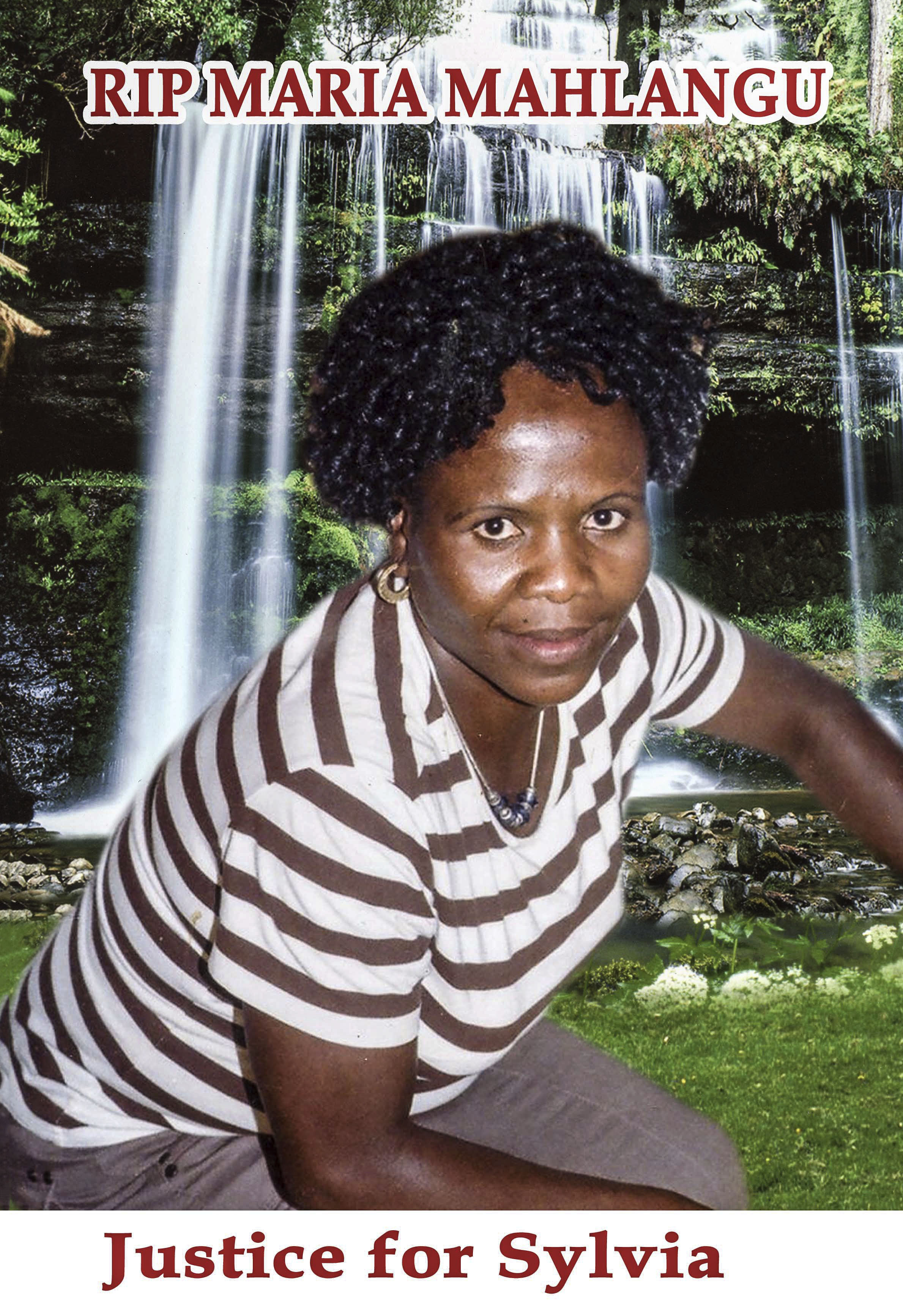

Denied: Maria Mahlangu died but the compensationlaw excludes domestic workers

Denied: Maria Mahlangu died but the compensationlaw excludes domestic workers

Last week, Seri filed an application in the Constitutional Court to confirm the high court order.

At a press briefing last week Nkosi said the department of labour was “not comfortable at all” with the Act being applied retrospectively.

“So they [the department] feared that suddenly there were going to be a whole number of domestic workers coming out of the woodwork all wanting to put in claim at the same time,” Nkosi said.

“And if all those claims are valid, where is the money going to come from? Because they say to us the scheme works on the contribution basis. So, because domestic workers were excluded, there was no obligation on employers to make contributions.”

The department had not prepared to make this argument in court, Nkosi said.

About R17.1-billion was paid out to beneficiaries by the fund last year. According to the fund’s 2018/2019 annual report, it has a deficit of R6.3-billion as compared to the surplus of R4.8-billion generated in the previous financial year. This represents a decrease in excess of 100%.

The fund’s net assets decreased from R32.4-billion to R26.3-billion.

Democratic Alliance MP Michael Bagraim said the argument by the labour department is “nonsense”. He is a member of the portfolio committee on labour.

“First of all, they have been warned by members of the portfolio committee for six years that they need to make contingency plans for domestic workers and they need to include them,” he said.

“And they always assured me in the portfolio committee that they are doing that work and making sure that the money is there.”

Bagraim suggested the fund draw from its investments through the Public Investment Corporation. According to its annual report, the fund’s investment portfolio increased from R65.9-billion in 2017/18 to R66.9-billion in the current year.

He added: “This is one of the worst excesses of apartheid and it continued into the new dispensation for 25 years. They can’t come now with an excuse about it costing a lot of money.”

Bagraim noted, however, that the fund’s capacity problems will make it difficult for it to administer claims.

The fund’s board recently received audit disclaimers because of its inability to collect contributions effectively and validate claims.

“Affordability is one thing. If they can actually deliver, it is another thing. I don’t think they can and this will add to their woes,” Bagraim said.

“But that is something they must tackle. It is not for the Constitutional Court to delve into whether they can do it or not. Domestic workers shouldn’t suffer because people are incompetent.”

The Compensation Fund did not respond to questions by the time of publication.