Finance Minister Tito Mboweni. (David Harrison/M&G)

NEWS ANALYSIS

Earlier this week, @RobinGwhiz tweeted that people should start to wash their hands “like you convinced your husband to kill the true king of Scotland”.

The tongue-in-cheek reference to Shakespeare’s Macbeth provided some much-needed comic relief in the face of increasing fears of the spread of the coronavirus and subsequent hygiene campaigns.

But as social-media users press the send button on their mildly dystopian jokes about the viral disease, it has become clear that the economic effects of Covid-19 will not be felt only at its origin in China but also around the world.

The South African government, like many of its counterparts, has signalled that it is prepared to deal with the Covid-19 outbreak.

On Thursday afternoon Health Minister Zweli Mkhize announced that the first case of the virus had been confirmed in South Africa, with further details set to be released later that day.

But beyond health interventions, the government also needs to prepare for the potential effects of global trade being disrupted.

Economic models currently point to global economic growth being two percentage points lower over the next 12 months, at about 1%. The revised growth estimates have been triggered largely by the outbreak of Covid-19. After the outbreak, China — which is one of South Africa’s biggest trading partners — saw its manufacturing purchasing managers index (PMI) drop to 35.7 in February, down from 50 in the previous month. This is the lowest drop of economic activity in that country’s manufacturing sector since 2004.

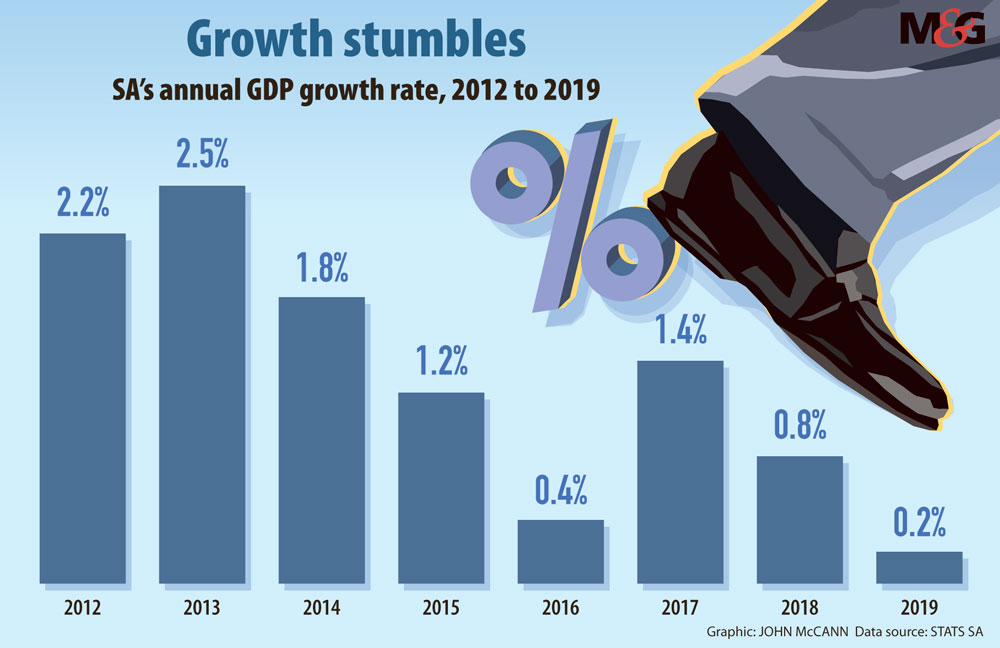

Earlier this week, South Africa’s gross domestic product (GDP) numbers for the fourth quarter of last year showed that the country had slipped into a technical recession after two consecutive quarters of contraction, with little prospect of recovery for the first quarter of 2020.

The last time South Africa was in a technical recession was in 2018, when power cuts by Eskom impeded the country’s growth prospects. This was preceded by the recession in 2008-2009, when the country’s economy was hard hit by the effects of the global financial crisis. That recession lasted nine months.

The South African economy grew by just 0.2% in 2019, according to Statistics South Africa (Stats SA). This is the lowest level since 2009, when the economy contracted by 1.5%. Stats SA data shows that seven of the 10 industrial sectors contracted in the fourth quarter, with the transport and trade sectors being the main drags on overall activity.

The hit on global trade as a result of a new strain of the coronavirus, and the power cuts implemented by Eskom, caused Momentum Investments economist Sanisha Packirisamy to revise the country’s 2020 growth prospects downwards, from 0.8% to less than 0.5%. This is lower than the South African Reserve Bank’s January 2020 estimate of 1.2% and the treasury’s 0.9% estimate, as announced in last week’s budget.

Shipping volumes from China are plummeting, as the effect of the coronavirus outbreak takes a deeper toll on production in that country. Data from the South African Revenue Service shows that China shipped more than R190-billion worth of goods to South Africa during the first 10 months of 2019. Exports to the Asian country totalled R116.6-billion.

Packirisamy said the country’s first-quarter GDP figures will be affected by supply-chain disruptions that have been triggered by the coronavirus outbreak.

Citadel chief economist Maarten Ackerman said although the Stats SA data shows that the country is in a technical recession, this is merely a statistical measure.

Ackerman said the country has been in recession since 2013 in terms of per capita growth. The country has been unable to grow more than 1% beyond its population growth, which currently sits at 1.4%, Ackerman said.

As a result, South Africa’s social issues — such as poverty, inequality and unemployment — continue to grow more acute, he said.

With the Chinese economy on lockdown since the outbreak of Covid-19, Ackerman sees an inevitable contraction in GDP for the first quarter of 2020. “By implication, this means that the 0.9% GDP assumption for 2020 is at risk of being overestimated and that [the] government is likely to reduce that number downwards soon,” he said.

Ackerman explained that if the coronavirus is not contained and the global economy tips into a recession, South Africa will be unlikely to achieve the goals of the recent budget as set out by Finance Minister Tito Mboweni last week.

If the government does not achieve its goals of reducing its debt, spurring growth and creating jobs as per the budget, Ackerman views a downgrade of the country’s debt by ratings agencies as inevitable.

The two consecutive quarters of negative economic performance, however, have failed to “shock” President Cyril Ramaphosa. He told editors in Cape Town this week that the figures are not “pleasing”, but that they also don’t come as a surprise “because the signs were there”.

“The signs were there that [drove] us to this lack of growth and this technical recession that we’re in now,” Ramaphosa said.

“It’s been load-shedding and the impact that it has had on production, both at the manufacturing level, as well as with trade.”

Throughout his briefing with editors, the president was upbeat about attempts to reform the economy, constantly referring to the “social compacts” that are being discussed on various fronts, including the public-sector wage bill.

Last week, Mboweni announced the government’s plan to cut the wage bill by R160-billion as part of its plan to cut spending.

The market responded positively to the wage announcement and others by the finance minister, but the fightback from public-sector unions and concerns about the government’s ability to implement the proposed reforms soon dampened the optimism.

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)

Unlike Lady Macbeth, chief economist at IQ Business, Sifiso Skenjana, believes that it is not too late to turn around the country’s tide, despite the economic slump.

“There is certainly an opportunity for a revival, as long as we start doing the right things and focus on implementing the structural reforms,” Skenjana said.

“There are structural issues that prevent the economy from growing and once we understand those structural issues it becomes a lot easier to know what interventions are needed.”

Thando Maeko is an Adamela Trust business reporter at the Mail & Guardian