the shock to the global economy from Covid-19 has been faster and more severe than the 2008 global financial crisis and even the Great Depression.

COMMENT

Rewind to February 2020. The South African economy was in a state of disarray. Two consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth signified a technical recession. The unemployment rate was hovering just below 30%. The estimates revealed in the 2020 Budget Speech indicated that we were teetering on the edge of a fiscal cliff, and that a Moody’s junk bond rating was imminent.

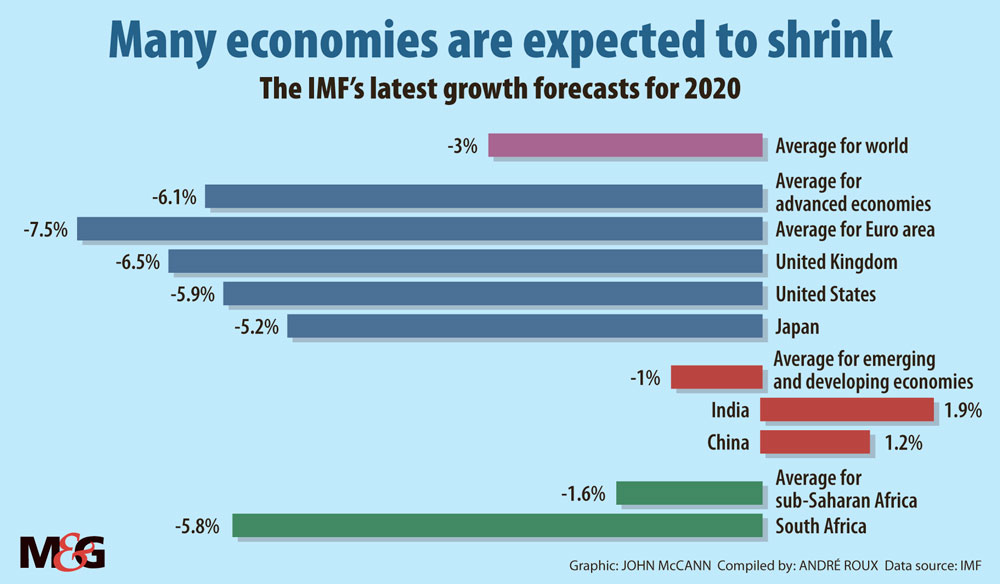

Load-shedding was a daily occurrence; the only question being what phase would prevail. The future of SAA was uncertain, widespread retrenchments were being announced and civil servants faced a salary freeze. The global environment wasn’t all that inspiring either. In the wake of ongoing trade tensions between the United States and China and an ideological shift in developed countries towards protectionism and nationalism, the world economic growth rate for 2020 was expected to be only slightly higher than in 2019 when the lowest expansion in a decade was recorded.

If only we had known that those would turn out to be the “good old bad days”. Within weeks, Covid-19 has turned the world on its head and fast-tracked a global slowdown that may turn out to be unprecedented. Covid-19 has already had an indelible effect on our values, expectations and hopes, as it infiltrates every crevice of economic activity. No business and no consumer — whether rich or poor, big or small — will be immune to the direct and indirect economic effects of the pandemic.

Now the question globally and domestically is not whether there is going to be a recession, but how severe the recession will be and how long it will last. Well-known analyst Nouriel Roubini points out that, “… the shock to the global economy from Covid-19 has been faster and more severe than the 2008 global financial crisis and even the Great Depression. In those two previous episodes, stock markets collapsed by 50% or more, credit markets froze up, massive bankruptcies followed, unemployment rates soared above 10% and GDP contracted at an annualised rate of 10% or more. But all of this took about three years to play out. In the current crisis, similarly dire macroeconomic and financial outcomes have materialised in three weeks.”

The answers to how severe and how long the recession will be in South Africa are dependent on the way in which a number of variables unfold and interact with each other over the next few days, weeks and months. One of the most decisive relationships is that between the transmission rate of the virus, and society’s concomitant response. Key considerations in this regard include the ability to “flatten the curve” and the time it takes to reach the peak infection rate; the institutional capacity to enforce lockdown protocols; the duration of possible extended lockdowns; the lockdown exit strategy; the capacity of the health care system to roll out widespread Covid-19 testing, tracing and critical treatment measures; and the fiscal and monetary response.

From this, two key issues emerge:

- The effectiveness of the health sector response; and

- The extent of (mainly) government-driven economic stimuli.

Until mid-April the economic stimulus packages announced were underwhelming. Thanks to its historically conservative stance, the SA Reserve Bank has been in a position to relax monetary policy, with more declines in the interest rate on the cards. The R500-billion stimulus package announced by the president on April 21 is certainly welcome. Although past fiscal indiscretions would in normal circumstances have prevented any meaningful injections, at roughly 10% of GDP the package compares favourably with the United Kingdom, France and the United States, which have injected resources totalling 18.9%, 13.6% and 10.7% of GDP into their economies respectively.

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)

Regarding the health sector response, the timing of the introduction of the lockdown, as well as the accompanying protocols appear to have been appropriate. It remains to be seen, however, whether this will buy enough time to enable an already beleaguered and stressed public health sector to deal with the peak infection period.

All things considered, the most favourable scenario (good old bad old days) is unlikely to materialise. In fact, right now the dice seem to be loaded in favour of either the Great Depression or Great Recession scenarios. The harsh reality is that the SA economy is shackled by pre-existing structural weaknesses, deficits and deficiencies; a hard landing is virtually unavoidable.

There are, however, two potential game-changers (or lifelines). The one is the development within the next few months of a cure for and/or a vaccine against Covid-19. This would obviate the need for a comprehensive and widespread intensive care capacity. The other potential lifeline is a far more controversial one.

Although the government’s general reluctance to do so is understandable, it is gratifying that the April 21 stimulus package is set to be partially financed through special pandemic-related funding from agencies such as the World Bank and the IMF. This is surely justifiable as long as the funds are used to assist those millions of South Africans whose livelihoods (and lives) are at risk.

Once the dust has settled, we will in all likelihood try to answer a variety of fundamental questions, such as:

- Will the post-pandemic era be characterised by greater global trust and connectedness, or will it fuel the nascent trend towards isolationist, protectionist, populist, and nationalist tendencies?

- Will the pandemic change forever the way in which we work, travel, and meet?

- Will the global power balance shift and, if so, in whose favour?

Finally, it is worthwhile considering that whereas a dead person cannot be brought back to life, an economy can.

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)

Professor André Roux is head of the Futures Studies programmes at the University of Stellenbosch Business School (USB) and former director of the Institute for Futures Research at USB