Charles Lessingh lies on the bed in his lounge in Welkom next to his wife Elsa. (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

In the golden glow of afternoon sunlight, Charles Lessingh lies on the bed in his lounge in Welkom, slowly dying.

A 10-metre tube runs from his nose across the cracked floor to the empty dining room where his oxygen machine is. Without it, the bedridden former gold miner can’t breathe.

“The tube is long enough so that he can get to the bathroom,” explains his exhausted wife, Elsa, her eyes circled by heavy bags. “Sometimes, he can’t make it, I have to help him get there.”

Three decades spent inhaling dangerous crystalline silica dust in Welkom’s gold mines has left the 56-year-old stricken with silicosis, an irreversible, progressive and incurable occupational lung disease.

He later lodged a claim for silicosis compensation with the Tshiamiso Trust. But while it found him medically eligible to claim for Class 3 silicosis (R250 000) in May 2021, it has been an agonising wait for his payout.

The Trust’s initial goal was to process claims within six months but there is a year and more delay before a claimant receives compensation, says Dr Rhett Kahn, a Welkom-based occupational and general medical practitioner.

“The delay in compensation is common and there is a backlog … of about 35 000 as there is a long delay when the mines have to check the record of service.” This is supposed to take no more than 90 days but is taking much longer.

Lessingh’s case is common, particularly with the higher amounts of compensation. “The R70 000 is paid quickly, the R150 000 to R250 000 not so quickly. The Trust admits they are paying more slowly than expected.”

Tshiamiso’s latest annual report notes how the “incredibly detailed” and “complex medical eligibility criteria” results in about 60% of claimants being certified as medically ineligible “and therefore not compensated”.

In 2018, Lessingh was medically boarded – the inability of an employee to work because of ill-health or injury – because of silicosis. “The mine said they would take care of everything and I would be paid out in a year or two but nothing happened,” he says hoarsely, amid severe coughing fits.

“His lungs are black, it’s like two stones together,” Elsa says. “His one lung is working only 3% and the other 20%. If I switch off the machine, there is no breathing.”

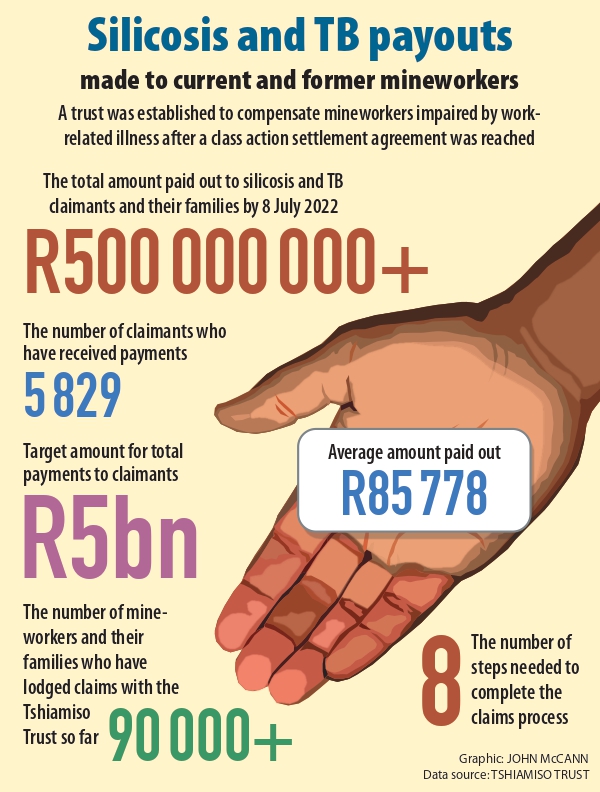

The Trust, which has been in existence since February 2020, was created to give effect to the R5 billion settlement agreement between African Rainbow Minerals, Anglo American South Africa, AngloGold Ashanti, Harmony Gold, Sibanye Stillwater and Goldfields and claimant attorneys in the landmark silicosis and TB class action lawsuit.

So far, it has paid out just over R700-million to 8 000 claimants, averaging 1 050 claims paid per month and 3 063 completed lodgements a month. About 97 000 mineworkers or their families have lodged a claim at 51 sites.

Rejected

However, Kahn says too many claimants are being misdiagnosed, incorrectly classified for compensation and rejected. He argues that the Trust is not prepared to have their results assessed by outside experts.

“They just do them quietly and we’ve got to accept what they say. It makes a significant difference because if it’s wrong, it’s R70 000 to R150 000 to R250 000 that a person loses. We submit people to the Medical Bureau for Occupational Diseases (MBOD), it finds them second-degree and can never work again yet the trust finds them normal – that there is nothing wrong with them.”

Daniel Kotton, the Trust’s chief executive, says it only appoints qualified and experienced service providers to conduct its benefit medical examinations (BMEs) and adheres to standards set by the national department of health and international standards.

“Regular audits and quality checks of equipment and premises are done to ensure that everything is in good working order and that the industry standards are met. The Trust has also built quality mandatory assessment tools into the claims management system.”

‘There’s no hope’

Elsa, frustrated the process was dragging on so long, approached a lawyer in Welkom who referred her to Kahn. Since the early 1990s, he has treated thousands of sick, impoverished gold mine workers suffering from silicosis and TB. His wife, Janet, helps them and their families navigate the complex maze of medical paperwork.

“In November, they [Tshiamiso] told us that the [Lessingh] money was on its way to Sars for clearing. Now, it’s more stories. Every time, it’s four weeks, six weeks … When I told that lady at Tshiamiso that he’s dying, she said I’m upsetting her. He’s in and out of hospital and they told him they can’t help him anymore, that there’s no hope.”

The frail Lessingh weighs just 53kg and is a shadow of himself. “I have to bathe him and change him by the bed, like a baby… He can’t walk. The heart must work harder for the lungs to work so there is no blood function in his body,” says Elsa.

Their small rented home is bare. They had to sell all their furniture to survive. “People need to see what the mines are doing to the people; how they must live after they work for them.”

Wasting away

In a 12-year timeframe, the Trust is responsible for compensating all eligible current and former mine workers across southern Africa with permanent impairment because of silicosis or work-related TB – or their dependents – who worked at qualifying mines during specific periods between 12 March 1965 and 10 December 2019.

About 25% of mine workers get silicosis, says Kahn, a medical adviser to the Justice for Miners campaign. It lobbies authorities for “fast and just compensation” for mineworkers and their dependents affected by TB and silicosis.

Most are scarcely affected in terms of their function – although at greater risk for TB – but about 5% are badly afflicted, short of breath and waste away, like Lessingh. About 400 of the 8 000 claimants the trust has compensated “will be bad”.

“Their life expectancy is lowered and is about five years from end-stage diagnosis. Most of these are black people dying in the rural areas, unknown to all. They will all end up like Mr Lessingh but without home oxygen and probably die more quickly.”

The Trust will pay 1% of Class 3 – “those 5% that are bad” – an extra R250 000 (total payment R500 000). “Who decides who gets and does not is not known as this will happen at the end of the Trust.”

John Mokoena is another patient who suffers with silicosis. (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

John Mokoena is another patient who suffers with silicosis. (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

‘Doing our utmost’

In all cases, the Trust “will do its utmost” to finalise a claim while the claimant is still living, Kotton says. “Unfortunately, there will be cases where claimants pass on before their claim is finalised.”

Processes and timeframes are built into the trust deed – the court settlement – with which the Trust must comply. “Similarly, there are cases where claimants might be oxygen-dependent or physically unable to complete lung function or x-rays required.”

Where claimants die before their claim is finalised, it must be taken over by an executor of the estate. When the trust is already in contact with the family, it helps arrange a National Institute for Occupational Health post-mortem to provide evidence required for certification.

Mammoth task

Insufficient documentation is the main reason for certification delays, Kotton says. “Claims related to dead mineworkers are especially difficult to process with limited documented information on the cause of death, which must be diagnosed as either work-related silicosis or cardio-respiratory TB to qualify for compensation.”

To help substantiate these claims, Tshiamiso has partnered with various government bodies and provincial health departments to access historical health data, unabridged death certificates, post-mortem reports and medical records from clinics and hospitals. “This is a mammoth task as most archives dating back to 1965 have not been digitised.”

For living claimants, the Trust relies on medical professionals and BMEs to confirm the presence of compensable disease. “These are time-consuming processes and the scarcity of and demands on occupational and pulmonary health specialists within the health sector in general, are compounding factors.”

The reality is that “there are many dependencies that are beyond our control”, he says. “It is now clear that the Trust’s initial estimate of six months to process claims was unrealistic. As the systems, processes and capacities are maximised, we may well be able to achieve this goal, but it is not the reality as yet, and managing expectations from claimants remains a daily challenge.”

X-ray bungle

In March, Matseliso Mokoena, a Welkom ex-mineworker, was told via SMS that the Trust had found him medically eligible to claim for Class 2 silicosis (R150 000). But when the sickly 56-year-old started agitating for his money, he was informed in July he had been found “medically ineligible”, with no evidence of silicosis found on his chest x-ray.

Richard Spoor Attorneys got involved and an investigation by the Trust found that an x-ray belonging to another claimant had been used. In a letter of apology to Mokoena last month, the trust blamed an “administrative error”.

Mokoena fails to understand how it happened. “The question is with my x-ray, it’s my name, ID number, my photo, fingerprint and industrial number,” he says. “…This is my money. But these people don’t want to give me my money.”

The statutory MBOD has since certified him with second-degree silicosis, or severe disease. “I live with pain in my body and have to sit outside at night to breathe.”

Mokoena survives on a disability grant and feels deep despair. “I was going to send my daughter to university, but she is sitting at home crying every day and having suicidal thoughts. She thinks I don’t want to help her because she knew I was going to get something from Tshiamiso and now I’ve come back with another story.”

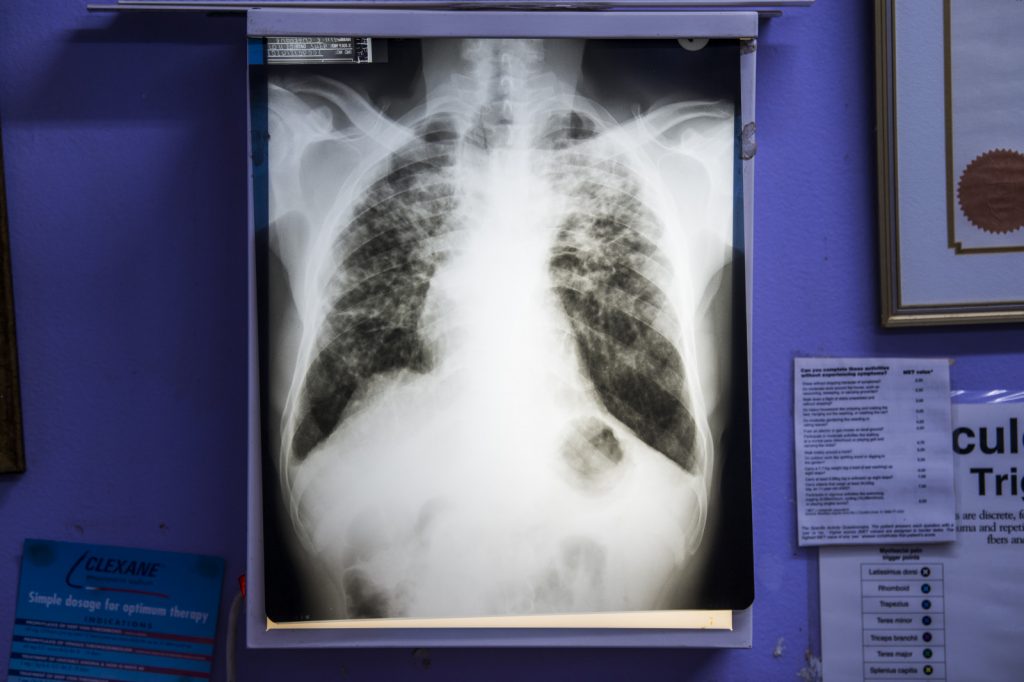

Silicosis is an irreversible, progressive and incurable occupational lung disease. (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

Silicosis is an irreversible, progressive and incurable occupational lung disease. (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

Enhancing the system

Tshiamiso says the system of checks in place at various stages in the claims process make the risk of errors like Mokoena’s low and “there are very few such errors”.

While this “mix up” is rare Kahn says, “it’s not a single occurrence as in mid last-year, the trust sent about 80 SMSs to the wrong people about findings”.

For Janet, the biggest concern is “who else has had their x-rays and lung functions mixed up” and how the Trust is detecting this. “If the lawyers had not gotten involved, we would still not know what was going on …. How many claimants are able to access this type of intervention?”

She often finds herself close to tears. “I’ve spent a large part of my adult life assisting mineworkers and have never felt as helpless as I feel now. Tshiamiso Trust seems to have taken the place of the paternalistic mines from the apartheid days… A lot of what they do is putting ticks in the relevant boxes and moving on in their own way, regardless.”

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)

No appeal mechanism – yet

That the Trust has still not set up its appeal mechanism – the Medical Reviewing Authority – 18 months after starting medical examinations on potential claimants is a “violation” of the trust deed, Janet says.

While the Kahn’s have submitted 38 appeals to it, “that there is no-one to adjudicate the appeal is exactly the problem,” she says. “We are hoping they are not lost; we are telling miners they have to wait until the appeal mechanism is set up, but we need to try and avoid appeals being repudiated because of the time limit imposed by the Trust Deed to appeal.”

Tshiamiso says its priority was to enable lodgements, medical examinations and certifications, followed by the reviewing authority. “Even though the full Reviewing Authority processes and system functionality was only recently completed, claimants have been able to log disputes since July 2021, shortly after lodgements commenced.

“To cater for the anticipated requirements … It is planned to increase the number of panel members for the Reviewing Authority.” The 30-day appeal window “may be restrictive”, Kotton says, and the Trust is seeking to introduce a 120-day period.

His small team has been “overwhelmed” by PAIA requests from claimants for access to their lung function and x-rays. “We are currently reviewing and streamlining internal processes to be more efficient and timeous in responding to requests for information through PAIA and other channels.”

Earlier this month, Lessingh, who is back in hospital, received a call from the trust: his claim had been finalised. “Hopefully, in a month I will get the payout,” he says, relieved. “It’s been a lot of tears, stress and struggles,” adds Elsa.

[/membership]