A prolific vocalist, Moonga K’s discography takes in R&B, rock and pop. (Rod Taylor/www.rodtaylor.co.za)

During the time the Mail & Guardian spends with Moonga K, the Zambia-born, Botswana-raised and currently South Africa-based musician name checks James Baldwin and Kimberlé Crenshaw. He then goes on an impassioned diatribe about George Floyd and the Black Lives Matter movement in America, as well as the black music history lessons his father shared with him and his siblings.

We geek out over a shared passion for SoundCloud (both of us having been early adopters of the platform); we trade tips regarding video editing platforms as he hips me to some mobile apps. I tell him what little I know of the work of African feminist scholars such as Professor Oyèrónké Oyewùmí, herself a towering figure in the field of sociology, a subject Moonga K says he cruised through at tertiary, despite not affording enough time towards studying it.

Our appointment seems haphazard: Sandton, on a Monday, at 2pm.

But we’re dealing with a man who’s got places to be, and other people to meet — like his band (with whom he performed in a streamed Lyric Theatre performance alongside Msaki on Saturday 10 July). Moonga K counts himself a follower of the East London-born songcatcher. Despite being a relative overachiever in the socially acceptable sense — he currently sits on a solid discography of three EPs, and multiple singles and features, and he has another album due later in the year — he struggles with impostor syndrome, which he’s revealed in other interviews as the source of his multiple mental breakdowns over the years.

This is where we dwell: mental health and its effects (which can be debilitating during the most urgent of times); ownership and control in the truest sense, an omnipresent desire in the singer/songwriter’s creative pursuits; and, curiously but not surprisingly, fashion, a nascent obsession of his.

We don’t talk much about Zambia, his land of birth. In Botswana, however, Moonga K dives head-first into his passions. He organises shows at the theatre with his friends; he starts writing songs; he falls in love time and again with his blackness — what with his father being a staunch pan-Africanist and all.

He also discovers SoundCloud, which he still credits as a top platform for music discovery, especially for left-stream artists.

But Botswana, population-wise, is small. And [its] small towns and cities are limited in their understanding of expression, artistic forms notwithstanding. Still, he organises and performs and does weird shit with his art homies. In the middle of it, a deep-seated discomfort overcomes him. He realises that everyone identifies with him as nothing else but a musician, so he quits.

For two years between 2014 and 2016 he moves to Joburg to lock in and flex his academic muscle. He also starts doing odd jobs at music festivals, the likes of Park Acoustics in Pretoria and Lush in Clarens, an experience which reignites his passion for music.

An EP, Free (2017), produced by his childhood friends Aqeel Williams and Shaun Masi, results. He uploads it onto SoundCloud, which is where Greg Carlin (erstwhile frontman of the rock band Zebra & Giraffe) discovers him.

“I remember it was so difficult for me to let go when the conversation of re-releasing the EP came up. It was like, I had to take it off SoundCloud. It was back and forth because I was like, ‘No, I don’t want to; it’s meant to be there, and it’s meant to be there alone,’” he recalls.

Moonga K pictured at The Marabi Club wearing custom designs by Levi’s Haus Africa. (Photo: The 1988 Films)

Moonga K pictured at The Marabi Club wearing custom designs by Levi’s Haus Africa. (Photo: The 1988 Films)

In retrospect, he didn’t know who he was as an artist.

“I’d just got back into music. Free was an EP that I was like, I think this is what I wanna put out right now; I think this is what I wanna speak about. I was 18 when I wrote those songs, 19 when I recorded them. I just told myself, if this is the first body of work I’m gonna put out, let it be honest and vulnerable.”

He gave in, ultimately. Free was re-released onto streaming platforms with an additional track, and its presence in Moonga K’s catalogue is a marker of one of the many phases the musician has yet to embrace.

“That was the first decision I had to make, and it was one of the best as well.”

Carlin also produces and records Wild Solace — a decidedly pop-sounding effort that sends Moonga K in a direction opposite to the alternative R&B route he’d taken prior; and introduces him to the artist services, A&R and music distribution company Platoon.

“[Greg] was such a huge mentor. He was introducing me to so many aspects of production and networking. So I was just like, ‘I don’t know what this music is, but let it come out, and let it flow.’ It was definitely influenced by his background in rock music, which I wasn’t opposed to since my dad made me and my sisters aware of the history of our blackness, and knowing that black people created rock.”

His father is a part-time reggae musician, while his mother is “super into gospel”.

“I was exposed to all types of music,” he says.

His new single, black, free and beautiful, is the sonic vehicle through which Moonga K bleeds out the influences from these two familial worlds. It’s Black Power music with a spiritual, gospedellic twist. It’s also assured of itself, and unapologetic in its funky stance.

“I’m black, free & beautiful/ this carefree me’s undisputable,” goes the refrain.

Moonga K started working on An Ode To Growth (2020) shortly after releasing Wild Solace. He recalls the turbulence of those early stages, and refers to the experiences as a tumultuous process. He was very confused.

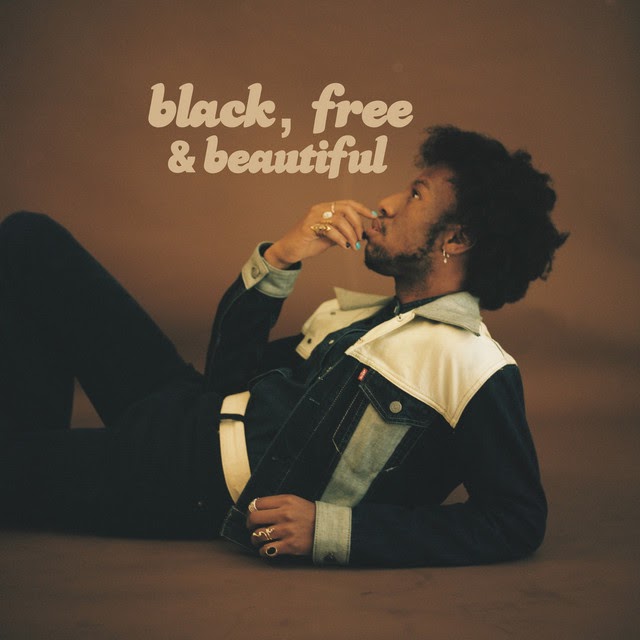

The artwortk to Moonga K’s latest EP black, free and beautiful

The artwortk to Moonga K’s latest EP black, free and beautiful

“I remember we were halfway through [the recording of] Wild Solace. I was in my second year at Monash, I think. That was the beginning of my proper unravelling in trying to find myself. I went through a huge breakdown where I shaved off all my hair. Prior to that, I was going through a huge identity crisis. I was bleaching my hair every two weeks. I had like, twelve different hair colours; I was just going through it.”

In a way, the move from Botswana made it possible to embrace his frail mental health; and to confront the bubbling depression and anxiety he’d been internalising while based there.

“I was in this space back home where mental illness wasn’t acknowledged. It was demonised, and it was seen as a white thing only. So I didn’t have the space to properly heal, and to deal with my depression. And then I moved here, and I was finally in a space of freedom, which I didn’t know how to deal with, being entirely by myself. I was so scared because I wasn’t opening up to anyone.”

He then sought professional help.

“I saved a bit of money, and I paid for my own therapy. My first proper therapist was a black woman who helped me heal. That was the beginning of my process of really dealing with my demons.”

Reconnecting with music allowed Moonga K to have fun again, and also gave him the opportunity to work with a vast array of talent across disciplines. These are the people who gave him advice, who provided inspiration, and who rekindled his childhood dreams.

“We need to feel validated, and feel like what we’re doing is worth it. But also, you validate yourself; I’m of that belief. You can’t really move forward unless you believe in what you’re doing, because that’s how others will believe in you.

“And I think I’ve been fortunate in the sense where I’ve been able to just put my ideas forward, and have the people around me connect with them, resonate with them, and be a part of it,” he says.

We speak about his aspirations, in conclusion, and he mentions the following: “I need to keep doing more. I’m not where I need to be at, I’m not known yet, I’m not a big dawg — which isn’t the goal, but my goal is to get the music to transcend, far and wide, and to have people connect with it and feel represented, or feel like their voices are amplified. I think that’s the most important thing.”

black, free and beautiful is available on Spotify and You Tube Music