A 19th-century image of an indentured labourer’s dance troupe in Natal. (Image courtesy of Campbell Collections, Killie Campbell Africana Library, UKZN)

The history of Mount Edgecombe, as told from above, is of the Mount Edgecombe Country Club Estate with Gateway and Cornubia Mall looming across the highway. But underneath this footprint of late-stage capitalism lies the history of the sugar estates and the people who worked on them — indentured labourers of South Asian descent, Black migrant labourers from Mpondoland, skilled Mauritian workers, workers racialised as Coloured, and white sugarcane plantation owners and managers.

Through Sathasiva Pillay’s new book, Sugar Mill Barracks: The Making of Mount Edgecombe, we are guided through the ecosystem of one of the oldest sugar estates and barracks in KwaZulu-Natal, the Mount Edgecombe Sugar Estate.

The self-published book is the result of more than 40 years of research on the way of life in sugar mill barracks during and after the Indian indentured labour system. This colonial labour system was conceptualised by the British as a way to maintain a cheap labour source to work on various plantations in the colonies after the abolishment of transatlantic African slavery in the British Empire in 1833.

Colonies such as British Guiana and Mauritius had already instituted indentured labourers from South Asia, and when sugarcane planters such as James Saunders advocated for Indian indentured labour in Colonial Natal, the British metropole and Indian government agreed that the profitability of Natal relied on it.

According to The International Aspects of the South African Indian Question, 1860-1911 by historian Bridglal Panchai, local Zulu populations were not seen as reliable workers in the fields by the British. Officials said they often left work to till their own lands and operated under the authority of local chiefs. They thought that segregation of the two main racial groups in the areas — the Europeans and the Natives — would lead to the colony’s prosperity for Europeans.

And so, in South Africa, the first group of labourers came from India in 1860, and migration continued until 1911. This controlled worker population had no claims to land of their own, families or clan or chieftain structures, which meant their absentee rates were lower, because they had no support structures or means to make a living outside the plantations during their indentureship. African labour, in the form of Mpondo migrant workers, replaced the Indian indentured labourers, who left the plantations after their indenture.

Indentured labourers weaving baskets in a sugar plantation. The labourers brought art, crafting and agricultural skills with them from India. (Image courtesy of Campbell Collections, Killie Campbell Africana Library, UKZN)

Indentured labourers weaving baskets in a sugar plantation. The labourers brought art, crafting and agricultural skills with them from India. (Image courtesy of Campbell Collections, Killie Campbell Africana Library, UKZN)

However, many of the Indian indentured labourers’ descendants continued working on the sugar estates. Pillay (who is better known by his nickname Sunny) is one of those descendants. His father, Appavoo Pillay, came from Thirupanjali in southern India to work on the sugarcane fields. After his indentureship ended, he moved around the North Coast sugar estates, and finally settled at Mount Edgecombe Sugar Mill, where he worked as a bricklayer. Pillay was raised in the barracks.

“At the mill I worked from the bottom up,” he says. “I started as a general labourer when I stopped going to school in standard four [grade six]. I worked as an office messenger —– a tea boy and messenger.” Pillay then worked his way to being assistant manager after a series of clerk positions. He attended school part time to upskill himself. “My father worked at the mill as a bricklayer, and because he did, I was employable in the Sugar Mill. You had that link. I came from the bottom, but that’s why I know what hard work is, because I went through that,” Pillay says.

In the book he explains that working for the mill was a “cradle to grave” affair, in part because of the housing offered by the Natal Sugar Estates. Sugar mill labourers qualified for free housing on the condition that, if their children worked outside the sugar estate, they could not live with their parents. “This forced parents to ensure that their children worked for the mill to continue living with them,” writes Pillay.

The book tells the story of how people lived in and amongst two overarching institutions: the Shree Emperumal Temple network (incorporating six different temples), which was founded by indentured labourers; and the Mount Edgecombe Sugar Mill, which was founded on the backs of indentured labourers. The Mill, part of the Natal Sugar Estates, became part of Tongaat Hulett Sugar in 1963 and was demolished in 1994 as its neighbour, Phoenix, grew in size and urbanisation needs outstripped sugar-production demand.

Sugar Mill Barracks is a short and clear-to-read introduction to the lives of the indentured labourers, with many of its 190 pages dedicated to full-page images from the temple’s photo archive. For those who haven’t witnessed a Kavady festival or a Chariot procession, the images provide valuable insight into the creolised Hinduism practised South Africa; the formal sports or school photos are a nod to the community that grew up in the barracks, perhaps included for older generations from Mount Edgecombe to find themselves, family and friends pictured.

Indian indentured labourers were a heterogeneous population with different linguistic, caste and ethnic groups working in the fields and on the mill floor together. The book captures some of this heterogeneity by looking at the interplay of Hinduism, Islam and Christianity in the barracks and how sport and schooling developed in different barracks’ communities.

Sugar Mill Barracks runs through the social, economic, cultural and religious aspects of labourers’ lives with fondness. (Photo: Niamh Walsh-Vorster)

Sugar Mill Barracks runs through the social, economic, cultural and religious aspects of labourers’ lives with fondness. (Photo: Niamh Walsh-Vorster)

“While the indentured settlers hailed from various parts of India, it was remarkable how historic differences were set aside on African soil. A strong community emerged!” Pillay writes. Although this community is characterised by Pillay as a place in which historic differences were set aside, he mentions how caste operated with precision on the plantation, and that the community was not racially mixed — each racial group had their own section of the barracks, further cemented by the Group Areas Act, which was also strongly enforced.

Sugar Mill Barracks runs through the social, economic, cultural and religious aspects of labourers’ lives with fondness; however, Pillay often refers to the indentured as “settlers”, falling into the oversimplified lexicon of arrival and settlement that elides the violence of both White settler colonialism and the system of indenture itself. Indentureship complicates notions of settlerdom — many indentured labourers were kidnapped, did not fully understand the contract they signed or thumb-printed, and their “arrival” and “settlement” in South Africa was not as an organic process as those two words may imply.

Indenture culture

Uncle Sunny and I are sitting in the Shree Emperumal Temple Association’s office, as the September winds whistle through the palm trees outside the building. Pillay, 79 years old, has served as the temple’s treasurer for more than four decades, and is still a member of the board of trustees. “With the book I had to take my retirement from the temple to write, but I’m a lifelong member, you know,” he laughs.

One of the primary functions of indentureship was to reduce people to units of labour; flesh and blood into an indenture number. But as Pillay reminds us, their lives were not just struggle and strife. Indentured labourers and their descendants had fun in the barracks. Dancing, drinking, reading, smoking weed, watching theatre and storytelling performances under the shade of the trees — any off-time was welcomed by the indentured who engaged in all of these leisure activities, according to Pillay.

Although the majority of the labourers were Hindu, many looked forward to Christmas time — the White sugar mill owners were Christian and so the entire mill enjoyed a break over the Christmas period. New Year’s Day also provided the workers with a break and you’d find most of the barracks community at the beach with sour dosas, liver curry, and puli sadam (sour rice) packed from home — a tradition that continues today.

Hinduism — in both formal and looser forms — was a big part of barracks life. The network of temples was built over time in Mount Edgecombe, but started with the Shree Emperumal Temple, a wattle and daub construction created in 1875.

Sathasiva Pillay outside the Shree Emperumal Temple, of which he is a trustee. (Picture: Niamh Walsh-Vorster)

Sathasiva Pillay outside the Shree Emperumal Temple, of which he is a trustee. (Picture: Niamh Walsh-Vorster)

Pillay gives us a fascinating biography of Kistappa Reddiar/Reddy, a prolific temple builder in South Africa, who was indentured to the Mount Edgecombe Sugar Mill. Temple building is both a calling and a practical skill — the divine made tangible through sculpture and brick, forming the networks for worship and working alongside natural features such as snake puttus [pits], old Banyan trees or streams.

Reddiar was a bricklayer by profession and had no formal training in temple building, but the barracks community asked him to create their temple to Ganesha (the deity worshipped for new beginnings and success), knowing he had worked as a builder in India. His work impressed those in other barracks, and Hindu communities along the coast of KwaZulu-Natal sought out his handiwork. Reddiar’s legacy is seen in the tall Hindu temple spires and ornate sculptures that have irrevocably shaped skylines across KwaZulu-Natal.

Theerukoothu, or Six-Foot Dance, was popular in Mount Edgecombe, and some of the earliest recorded Theerukoothu performances come from this area. The folk dance, which originates in southern Indian villages, was first practised by priests, and melds acrobatic dancing with dramatic retellings of scriptures from the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. The performances would be held over religious festivals, and Pillay memorialises Six-Foot Dance icons in South Africa such as Pattu Govender, Coochie Thumba, Ramsamy Govender and Gadajalam.

Historian of the cane cutters

“From a young age I was very interested to know anything about history. I’m a believer of facts. When I was a teenager and working at the mill, I used to interact with old people during my lunch break — old people were my friends and I used to hear their stories,” Pillay says.

One of those stories told by the elders weaves colonial resistance with magic. Malayali workers were employed by the Mount Edgecombe Sugar Company, and “it was rumoured that they were well-versed in Malayalam Shastras, an ancient book of Mantharam [book of magic/tricks]. Other indentured labourers feared the Malayalams. It was apparent they possessed magical powers,” writes Pillay in Sugar Mill Barracks.

These Malayali workers would relax under the shade of a tree, chewing betel nut, while their hoes levitated and weeded the sugarcane fields. These workers scared the white supervisors, and were apparently deported back to India.

Another story told of workers being abused on the mill floor by a white supervisor; the Malayali workers intervened by casting a curse that stopped the machinery from crushing sugar cane. The mill engineers couldn’t tell what the problem was. The white management, already suspicious of Malayali workers because of their affiliations with trickery and witchcraft, deported these workers too.

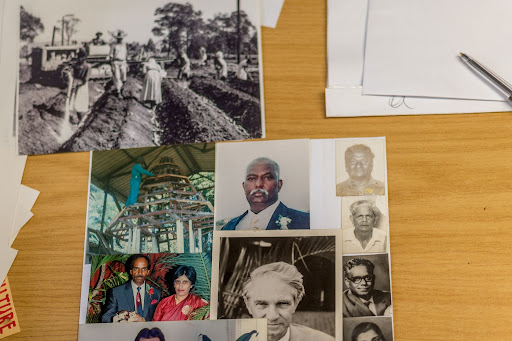

Much of the book’s visual material was culled from Sathasiva Pillay’s archives, which he has kept since the 1970s. (Picture: Niamh Walsh-Vorster)

Much of the book’s visual material was culled from Sathasiva Pillay’s archives, which he has kept since the 1970s. (Picture: Niamh Walsh-Vorster)

It’s taken Pillay four years to write his book. It could have easily been double its length, he tells me. “But I wanted the book to appeal to anybody, and I didn’t want it to be too big.” There’s a lot more history to excavate about the place, and although Pillay concedes his memory isn’t what it used to be, he’s still dedicated to archiving indentured and barracks heritage. His office is filled with black concertina folders neatly titled “Chariot festival”, “Emperumal Temple + Hall”, “Mariamman/Kali/Gengai”, “Ganesha/Muruga” and “Sports/School”, and he shows me all photographs, files and documents he needs to wade through.

“Somewhere in the 70s I started collecting pictures – you know, talking to people, asking anything about the barracks, anything about the mill. At the time I had no idea that I’d put it into a book. I’ve collected over 1 000 pictures in the temple archive,” he says.

With 40 years of research in his pocket, Pillay became the go-to person at the temple to field questions from students, academics, and journalists about the history of the area, indentured labour and the temple.

“Every time they come and meet me here, most of the time they go, ‘Uncle, you’ve got such a vast knowledge of Mount Edgecombe: Why don’t you put it in the book?’, but it never got into my head, you know. As time went on, I felt ‘Well, nobody knows the history as I know and I’m not gonna do justice to the former residents of Mount Edgecombe if I don’t put this in a book’”.

With the book finally published, Pillay says he’s going to continue meticulously documenting each image in the temple’s archive for the next generation of indenture scholars, history enthusiasts, academics and students. The temple committee would like to create an exhibition of the temple’s visual archive, too. Most of all, Pillay wants the former residents of the Mount Edgecombe barracks to know that they are seen, and their lives recognised in all their complexity.

You can order a copy of Sugar Mill Barracks from the Shree Emperumal Temple by emailing: [email protected].