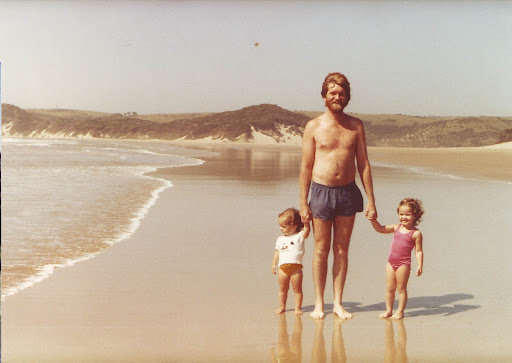

Clea and Theresa with their father, Clyde Mallinson. The family spent many happy beach holidays at Crawford's Cabins in Chintsa East in the 1980s. Photo: Brenda Mallinson

“Close your eyes. Imagine a place where you feel happy. Where are you? What do you see? Hear? Touch, taste, smell? Connect with your body and all its senses …”

I’ve done several variations of this exercise over the years (belonging to writing groups and being in therapy will have that effect), but my answer is always the same. The beach at Chintsa in the Eastern Cape.

It’s difficult for me to describe this beach: I connect with it through my spirit, rather than in words. The sand is, well, sandy (it was only when I visited Brighton’s stabby pebbles, that I realised this wasn’t a given); the waves are sometimes a little wild (none of that gentle Mediterranean nonsense), but never too scary; the water can be bracing, but it is warm enough for swimming.

In short, it’s a proper beach; the kind you conjure up when you hold a seashell to your ear and hear the faint echo of the roaring waves.

Holiday tradition

I’m not sure how old I was when my family first visited Chintsa — at a guess, perhaps four years old — but some time in the early 1980s holidaying there every January became a tradition.

Theresa and Clea Mallinson stop for a rest on some handy beach furniture during the ‘long’ walk to the lagoon at Chintsa. Photo: Brenda/Clyde Mallinson

Theresa and Clea Mallinson stop for a rest on some handy beach furniture during the ‘long’ walk to the lagoon at Chintsa. Photo: Brenda/Clyde Mallinson

We stayed at Crawford’s Cabins in Chintsa East, which was then owned by the larger-than-life Roy Crawford. It was a rustic resort, perfect for a young family: the small, whitewashed bungalows didn’t have electricity (the few appliances ran off gas), but they did have everything we needed, which wasn’t much. No television; no interwebs (it wasn’t yet invented); just a small, purple, portable radio, on which my parents would, occasionally, listen to the news.

We didn’t spend much time inside anyway. Even the walk to the beach was an adventure, as my sister Clea and I stretched our short legs to make our way down the tyres forming a narrow path through the thick coastal scrub.

Once at the beach, there was plenty to keep us occupied; when our childish attention spans tired of frolicking in the waves or building sandcastles, we could walk to the far-off lagoon in Chintsa West.

If we had enough energy to push on past the lagoon we’d arrive at the rock pools: a watery treasure trove of shining shells and sparkling sea creatures. Our favourites belonged to the sea anemones — “pumpkin shells”, we called them — which we’d collect for my father to string into necklaces for us.

When the wind rose in the early afternoon, we’d make the trek back up the tyres, rinse off our sandy toes at the tap, and proceed to the swimming pool. If we were lucky, there’d be a communal seafood braai around the pool in the evening.

At that time, Clea and I were picky eaters. I can’t imagine us enjoying the seafood, if we ate it at all; what I do recall is the warm glow of conviviality and the excitement of staying up “late” with the adults.

Then, the next day, we’d do it all over again.

Clea, Clyde and Theresa Mallinson on the beach at Chintsa. You can see Buccaneers Lodge & Backpackers as it was in the 1980s in the distance. Photo: Brenda Mallinson

Clea, Clyde and Theresa Mallinson on the beach at Chintsa. You can see Buccaneers Lodge & Backpackers as it was in the 1980s in the distance. Photo: Brenda Mallinson

Seaside sojourn

When I was in standard one, my father, who was then a geology lecturer at Rhodes University, went on sabbatical. And so, for the last three months of 1989, our family went to live at Crawford’s. Our bungalow for this extended sojourn was next to the trampoline, meaning we were in the prime location, at least to my nine-year-old mind. My father learned to paddle-ski, rather than wading through the box of academic papers he had photocopied; my mother looked after our little brother, Nathan; Clea and I went to a new school, Lilyfontein.

Lilyfontein was a “farm school” and its relaxed, dual-medium instruction was a far cry from the hothouse atmosphere of our private school in Grahamstown. There was less homework; more time for the beach (and for bouncing on that trampoline). We even got to take a bus to and from school each day. I can still remember the opening lines of the school song: “Lilyfontein, Lilyfontein, ons is trots vir jou.” And I was. When you’re happy, other emotions fall more easily into place.

Happy place

Sometime in the early 1990s, Roy Crawford sold Crawford’s Cabins to his son, Ian, and opened a new resort on the other side of East London. It was called Palm Springs. There were definitely palm trees, but the “springs” part of the name was a bit of a mystery; it certainly didn’t describe the mucky lagoon.

Nonetheless, our family duly decamped there for our January holidays. “We care about people, not places,” my father explained. I was old enough to appreciate the sentiment — admire my father for his loyalty, even — but I never quite warmed to Palm Springs; it just wasn’t Chintsa.

As I grew older, holidays with family — later with friends or alone — drifted away from that section of the coast. We went to Port Alfred, Plettenberg Bay, Cape Town; Durban and Mozambique in the other direction. My happy place was in my head — and in my heart — but I no longer replenished my memory well with a visit each year.

Things change

Until recently, I had revisited Chintsa only twice in my adult life. The first time was when I was 18 years old, having just finished matric. My family went on an excruciating housesitting “holiday” in East London, and visited Crawford’s for a day of respite. The beach was still there, but everything else seemed to have changed. Small bungalows had become two-storey monstrosities. It felt as if this were now a place for “rich people from Jo’burg”.

The rockpools at Chintsa, where Theresa and Clea Mallinson used to collect shells in their childhood. Photo: (Theresa Mallinson)

The rockpools at Chintsa, where Theresa and Clea Mallinson used to collect shells in their childhood. Photo: (Theresa Mallinson)

My adolescent self couldn’t comprehend that the memories in my mind no longer matched the physical reality in front of me. I remember my family going on a beach walk with Anne Knott, Roy’s daughter. “I wish this whole place would burn down and we could build it all over again — just like it used to be!” I exclaimed. “You’re quite the little idealist,” Anne observed wryly. She wasn’t wrong.

(At this juncture I must ask Ian — and his son Mark, who now runs Crawford’s — for their forgiveness; I wish to renounce such a fiery opinion.)

The second time I visited Chintsa was in, I think, 2013, when Crawford’s was the venue for a long-weekend media workshop. Now I, myself, was one of those “rich people from Jo’burg”, staying in a room in a double-storey cabin, even if my accommodation were not for my own account. Again, things had changed — there was even a restaurant. And I was here to work: my colleagues and I sat inside in a kind of boardroom the whole day, breaking only to eat.

But I remember, on our first evening, running down to the beach as darkness approached; the confusion I felt when the “secret”, jungly path I had always known was no longer there, and I had to backtrack and go a long way round. When I reached the sea though, the waves on my toes brought me right back home … even if only for three, short days; a flying visit.

In April this year, I went on a 10-day holiday to my parents’ flat in Plettenberg Bay. After more than a year of contending with our Covid world — the isolation; the ongoing salary cuts; the chronic overwork; adjusting to four editors in little over a year — it was just what I needed, or so I thought.

It was a very nice holiday. I read a lot of books, which brought me back to myself, a little — for me, one of the pandemic’s most pernicious, if tangential, side effects was the bewildering fact that I was no longer capable of reading for pleasure. I ate a lot of good food, sprinkled as Plett is with pleasant outdoor dining options (I can highly recommend Enrico and Ice Dream Land).

The view over the lagoon and beach from the Buccaneers’ deck that soothed Theresa Mallinson during her break. Photo: (Getty images)

The view over the lagoon and beach from the Buccaneers’ deck that soothed Theresa Mallinson during her break. Photo: (Getty images)

Soon enough I was back in Jo’burg, but something was still wrong. It was as if I had never been away; my holiday had not fortified me with any sustenance for the months ahead.

Some days, I wept before work. Exhaustion, tick; cynicism about my job, tick; reduced professional efficacy, getting there. Classic burnout, accompanied by my old foe, depression.

Place of healing

In some way, I always knew this was creeping up on me. Right at the beginning of the pandemic — when no one really knew what was happening, or how long it would last; when I lived entirely alone for four long months — I reflected on the fact that, in many instances, the advice for trying to flatten the Covid-19 curve dovetailed with patterns I fall into when I’m depressed. Isolate yourself; don’t go outside to exercise; blur the boundaries between your work and personal spaces; on no account socialise or see your friends.

“This is risky for you,” whispered a little voice in my head. “You should start seeing your therapist again.” I ignored that voice — for more than a year. Denial and avoidance are also familiar, destructive behaviours I cling to when I become overwhelmed. When confronted with a fight or flight situation, I invariably choose the third option: freeze (and then stay stuck).

The pandemic was — and is — devastating for all of us living in the third decade of the 21st century. Most people have suffered far more than me: I wanted to keep on keeping on; to show I was okay — but I wasn’t. Eventually, around the time the morning crying began, I realised I couldn’t continue in this fashion.

I called my doctor; I emailed my therapist. Back on the happy pills and accepting some much-needed guidance in navigating my life. “I’ll book you off for a week,” my doctor said. “I need two,” I insisted. He raised his eyebrows. “That’s pushing it, but okay …” It felt good to assert my needs. I ended up taking another week of annual leave, for luck.

“Are you sure you should go on holiday when you’ve been booked off sick?” my mother asked when I told her my plan. But I knew that three weeks of lying in bed all day or lounging around watching the 24-hour news cycle was the very opposite of what I needed.

But where to go? The warm waters of Tofo in Mozambique were tempting. Alas, international travel didn’t seem prudent, even though we were between waves. “Why don’t you go to Chintsa?” my father suggested. And, at that moment, something just clicked.

I didn’t go to my childhood spot of Crawford’s — these days it is both beyond my budget and not quite to my taste. Instead, I booked at Buccaneers Lodge & Backpackers, in Chintsa West, on the other side of the lagoon (but before the rockpools).

Theresa Mallinson’s break at Buccaneers Lodge & Backpackers in Chintsa in May helped her to reconnect with herself – and other people. Photo: Theresa Mallinson

Theresa Mallinson’s break at Buccaneers Lodge & Backpackers in Chintsa in May helped her to reconnect with herself – and other people. Photo: Theresa Mallinson

Buccaneers has electricity, but no television; there is WiFi, but only in the communal areas. Deleting Gmail and Slack — even Twitter! — from my phone and temporarily exiting the work WhatsApp groups provoked a spark of joy I didn’t know I still had in me. Or perhaps it was another emotion: pure relief.

“Won’t you be bored, going on holiday for almost three weeks by yourself?” more than one person wondered out loud. But I knew I wouldn’t be. I’d have my books and the beach and a break from real life: What more could I possibly want?

Buccaneers, like Crawford’s, is a family business, run by siblings Sal and Sean Price. For reasons of economy, I’d booked a small cabin with shared ablutions. When I met Sal, she took one look at me and realised I was too old (and perhaps a little too fragile; precious, even) for this arrangement. I was upgraded, at an extremely reasonable price, to a small seaview cottage, with my own kitchenette and bathroom, complete with a sparkling mosaic lizard in the shower.

People and places

After I’d moved from my initial room, it was time to hit the beach. It was lucky bean season and the path past the lagoon was strewn with the bright orange and red seeds. I picked some up and put them in my pocket to take back to Jo’burg. This seemed serendipitous; a good omen.

“Close your eyes. Imagine a place where you feel happy. Where are you? What do you see? Hear? Touch, taste, smell? Connect with your body and all its senses …” But I no longer had to imagine: casting off my dress and running into the waves, I was back where I belonged, in my happy place.

I settled into a routine. Every morning I’d go for breakfast on the Buccaneers’ deck, with its unmatched view of palm trees over the lagoon — and of the beach and sea beyond. I’d chat to Sal while she was busy making breakfast; every morning, she told me I looked happier and more relaxed than the day before.

After breakfast, I’d have another cup of coffee (sometimes spiked with my Aunt Sharon’s CBD oil, although I didn’t really need it; my surroundings were calming enough) and lie on the couch on the deck and read.

Every morning, I’d exhort myself to leave the comforts of the deck, stop gazing dreamily at the gorgeous view, and get to the beach before the wind rose. Sometimes I made it in time; sometimes I didn’t, but, as the knots in my stomach slowly began to unwind, I realised it didn’t actually matter.

Whenever I finally made it to the beach, I was greeted by the gentle moos of the village cows, grazing on the scrub by the lagoon. More cows than people; that’s how you know you’ve found a proper Eastern Cape beach. I’d go for a soul-refreshing swim; then, perhaps a walk to Crawford’s for lunch, which took all of 10 minutes — not at all the long pilgrimage of my childhood.

Village cattle on the beach at Chintsa. You know you’ve found a proper Eastern Cape beach when there are more cows than people. Photo: Theresa Mallinson

Village cattle on the beach at Chintsa. You know you’ve found a proper Eastern Cape beach when there are more cows than people. Photo: Theresa Mallinson

Evenings I spent chatting to the staff and the few other guests before an early night. Covid meant business wasn’t good; selfishly, for me, it meant there were just the number of people I could handle being around. Weekends were for socialising and it was a novelty to have a parade of visitors: my Visser cousins; the “East London Mallinsons”; and my Twitter friend, the writer Megan Ross, who I delighted in meeting in real life.

As the younger Vissers scrambled up the sand dunes, and Megan’s son Ollie played in the rockpools, I could see the ghosts of Theresa, Clea and Nathan from more than three decades ago watching over them.

I realised that my happy place isn’t merely a landscape of sand and waves, lovely as there are; it is populated with humans, too. My conversations with Sal, in particular, were a balm.

How do I describe her, and what she gave me? “Salt of the earth” is a (cliched) beginning, but there’s much more to Sal than that. Resolutely nonjudgmental, she’s generous in giving of her friendly ear — and huge heart. I could sense her frustration about the devastation that Covid had wrought on Buccaneers, but she was always busy figuring out how to keep on going. Sal also knows enough about this business called life to spend time in her artist’s studio each morning to nurture her creative spirit.

In short, Sal was just the tonic — and role model — I needed at this time of my life. As my father taught me all those years ago: places can have a special space in our hearts, but it’s the people who make them.