Lucky Michaels (right), businessman and owner of the iconic Club Pelican, pictured with some of the patrons. (Photo courtesy of Arena Holdings)

Club Pelican, located in an industrial park in Orlando West, Soweto, was off the beaten track. It was near Orlando West’s swimming pool and its matrix of railway and industrial infrastructure. In a different time and place, this would have been a prototypical nightclub location, except for the fact that there was no local precedent to follow. This was Soweto’s first nightclub.

Initially called Lucky’s and springing up in the early seventies (1973, according to an archival Drum clipping), the Pelican’s impact on the Soweto cultural landscape was immediate. Lorded over by the charismatic Lucky Michaels, the club became the jewel in a collection of family businesses.

It boasted a diverse pool of talent in its succession of house bands and an A-list of ghetto fabulous singers as its cabaret stars. Its VIP section was a veritable who’s who of Soweto society and its stage, hosting a mix of the day’s pop culture infused with the creativity and individual histories of the musicians creating it, reawakened a live music scene lacking dynamic venues.

“Lucky Michaels, being Lucky Michaels, created a vibe around the Pelican,” says Kgalema Motlanthe, the country’s former president and deputy president, a one-time operator of a nearby bottle store where rehearsing Pelican musicians frequently came to quench their thirst.

“There was the Donaldson, Uncle Toms, Bapedi Hall in Meadowlands, Naledi Hall and so on. So musicals like those by Gibson Kente would be performed in those halls, like the YMCA in Dube and so on. The Pelican was basically the first club with a resident band. You could have a meal and those who took alcohol would have alcohol while the band would be performing. It introduced that kind of nightlife in Soweto itself.”

The outside of the Pelican building in an Orlando industrial park. (Image: Google Maps)

The outside of the Pelican building in an Orlando industrial park. (Image: Google Maps)

Even as it leaned towards a top 20 musical culture on the weekends and a cabaret one on Sundays, the club had a healthy jamming scene that drew the top musicians of the day out of their usual band formations during house band breaks, sparking ideas that would later be committed to tape.

“All the great guys came there,” says one-time house band member, saxophonist Khaya Mahlangu, himself a former jamming guest. “From tenor saxophonist [Winston] Mankunku, to The Drive horn player Mike Makgalemele, saxophonist Barney Rachabane, Themba Koyane, Themba Mehlomakhulu, guitarist Allen Kwela, bassist Sipho Gumede, and pianist and saxophonist Bheki Mseleku … I’m talking trumpeter Stompie Manana and guitarist Baba Mokoena, who played a very pivotal role in my development.”

Sunday’s cabaret drew names such as Anneline Malebo, Marah Louw, Mary Twala, Thandie Klaasen, Sophie Mgcina, Abigail Kubheka, Thoko Ndlozi, Thandi Seoka, Felicia Marion and others.

In a Sunday Independent review of singer Marah Louw’s book, It’s Me, Marah, journalist Sam Mathe says that jazz, soul, blues and mbaqanga found expression inside the club’s doors. However, the dynamic of how these different elements shared space lay in the institution’s bootcamp-like practising, jamming and playing regimen, supervised, to some degree, by stage manager and drummer Dick Khoza. Although the house bands changed formation and names, it would seem, anecdotally, that the Afro Pedlars, who took over after Durban Expression when they split up, held court for much of the Pelican’s existence, at least from the mid-to-late seventies.

“Friday and Saturday the band played their own material,” says Afro Pedlars veteran Mahlangu. “By own material, I mean material of their own choice. We’d play jazz standards for the first set for like two hours. Straight ahead jazz. After that, we’d mix it up with groovy stuff because it’s a nightclub. So we played all the poppy tunes. Top 10s and top 20s and all kinds of music. And then on Sundays there’d be a cabaret, like five to six singers that night, performing five to six songs each. We had to learn the material from Tuesdays. You can imagine, in a week, memorising an average of 30 songs. It was a good grounding in terms of stamina and determination.”

Stompie Manana was a mainstay of the Pelican scene, joining the house band after dropping by during a rehearsal. (Photo: Stompie Manana/Facebook)

Stompie Manana was a mainstay of the Pelican scene, joining the house band after dropping by during a rehearsal. (Photo: Stompie Manana/Facebook)

Trumpet and flugelhorn player Stompie Manana, a nine-to-fiver in those early days, says he had come around the Pelican one Saturday morning during rehearsals, just to check out the scene, and wound up in the horn section. “They only had bass, guitar, drums and piano when I joined,” says Manana.

On one of those Saturdays, Michaels was within earshot and the band frontman, the recently departed Mac Mathunjwa, was putting Manana through some paces. Liking what he heard, Michaels turned to Mathunjwa and asked: “Is hy die een dat het Hugh Masekela trumpet geleer? [Am I hearing the guy that taught Hugh Masekela how to play trumpet?]” Mathunjwa answered, “Yes”, to which Michaels responded. “I need him. He plays nice, man.” Manana’s raspy, animated tone, infused with 86 years of musical and social history, is hard to translate to text, but it helps to encapsulate the sense of the Pelican as the country’s top laboratory.

Veterans of the Pelican scene, like guitarist Themba Mokoena, who joined the Pelican house band before it even had a name, say it was in the jam sessions where the flame was the bluest. “That was where you’d sharpen your skills,” he says. “You had to know what you were doing in front of Mankunku and the likes. In a sense, the Pelican was a school. We learned and practised with standards. We had to learn the various parts of the prescribed songs. There were compositions, but they weren’t at the fore. The jam sessions were like the space in between that facilitated learning from each other, like in a university.”

Although the jam sessions helped to swing the sound in different directions and the jazz was heavily laced with mbaqanga and other styles, Mokoena says, at the end of the day, the Pelican fancied itself a jazz club; the Soweto soul scene, for example, dominated by much younger musicians, operated more or less parallel to that, at venues like Mofolo Hall.

“I was with the Beaters at the time,” says Sipho “Hotstix” Mabuse, “but to improve my skills, I needed to interact with different musicians as well, people like Bheki Mseleku, Bra Dick Khoza, who was a mentor at the time.

“My first jam session, as a drummer, was with Bheki Mseleku [a key member of the Durban Expression] But in most cases, he’d be playing with [drummer and percussionist] Dick Khoza there. There was [bassist] Sipho Gumede, all those guys … It was a place where if you wanted to play with serious guys, like Bra Stompie Manana and so on, that’s where you found the real players at the time. These jam sessions happened not only as rehearsals, but also during performances when the house band took a break. That’s when different musicians would come on and jam.”

Khoza’s role as musical director and sometime musician was immense. “He was the [stage] manager of the club but he played an important role in terms of guidance and being diligent in your craft,” says Mahlangu.

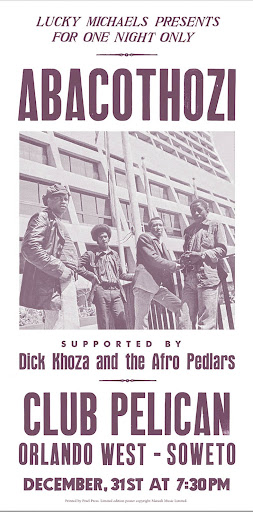

A Seventies-era poster for an Afro Pedlars and Abacothozi New Year’s Eve gig. (Poster courtesy of Matsuli Music)

A Seventies-era poster for an Afro Pedlars and Abacothozi New Year’s Eve gig. (Poster courtesy of Matsuli Music)

“Although the guys were not [formally] musically educated, they had great ears. They could tell you if you were not following your chord progressions. Dick would scold you. Even swear at you. All he wanted was the best from you so you had to work hard to be in the band. He’d say: ‘Sizobiz’ uMankunku, nangu uyakhala uthi akanajob. [‘We’ll call Mankunku, he could use the work.’] Then I’d go home and practise very hard. But he didn’t mean it maliciously.”

When Khoza hit the studio with his own recording, Chapita (which was released in 1976), he turned largely to his own house band, the Afro Pedlars. The recording includes Negro Mathunjwa on drums, Mac Mathunjwa on electric piano, Themba Mokoena on guitar, Bethuel Maphumulo on bass, Joe Zikhali on rhythm guitar, Khaya Mahlangu on tenor saxophone and Ezra Ngcukana on tenor and soprano saxophones. The recordings also featured Themba Mehlomakhulu on trumpet.

The grooves displayed throughout Chapita are sinewy; synonymous with jazz funk, but with a palpable township swing beneath them, as well as strong solos.

Abacothozi’s Night in Pelican wears its African influences in a more pointed way, and features some players who would also gather under the banner of the Afro Pedlars. Embodying the spirit of a groove-based jam session, with nimble, syncopated rhythms and assured vamping, the cuts in the record are suggestive of up-to-the-minute global styles being given hyperlocalised makeovers in the mbaqanga tradition.

Of course, a fair amount of the magic of the Pelican had to do with the vibe of the place, which contributed to how the music went down. A lot of its appeal, says Motlanthe, boiled down to Michaels’ flamboyance and reputation.

“There were people we knew in the township, if you like, as impresarios,” says Motlanthe. “There was an old man, Harry Mikela, John Dube and a few others who were known, [like] Ray Nkwe, who used to organise jazz festivals at the Moroka Jabavu Stadium, and later at Orlando Stadium. From time to time there would be a popular musician coming from the United States, and they would organise these. It was linked also to boxing. They’d bring professional boxers like Hurricane Carter, who fought Joe Ngidi at Orlando Stadium. All this was kind of linked together.”

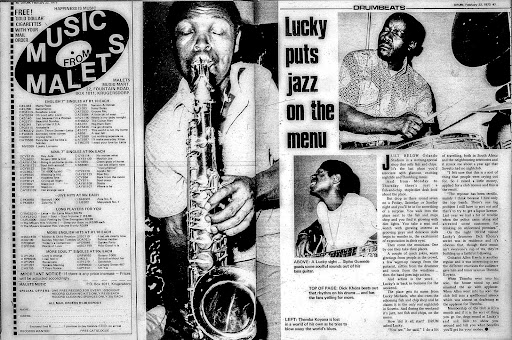

A Drum article about the Pelican from the Seventies.

A Drum article about the Pelican from the Seventies.

Michaels’ father and mother came from Malawi and Mozambique, respectively. The family ran a restaurant in downtown Johannesburg (before it was disrupted by the Group Areas Act). Otto, Lucky’s younger brother, was among the traffic officers in the city, of whom very few were black, says Motlanthe. Lucky, on the other hand, was among a group of bootleggers who apparently styled themselves after the Italian mafia. There was a fair amount of grit and street cred to the guy, and his venue, of course, doubled as a shebeen.

“I played in the very first band that opened the Pelican,” says guitarist Themba Mokoena. “It didn’t even have a name. So I got to know Lucky for quite a bit. You’d never say he was the owner. He never really carried himself like one. He’d sit with us and drink with us.”

Others, too, remember the contrast between the reputation that preceded Michaels and the image of his club. “The Pelican never had rough people there,” says Manana. “There were no fights. It was a very decent joint, man.”

And so the Pelican, the jewel of Soweto, continued to sparkle into the late seventies, when some of its lustre was taken by the opening of the Club New York City in Fordsburg, boasting The Rockets as the house band.

With the clarity of hindsight, the Pelican is remembered as the place where musicians went to be inducted into an elite club. Latter-stage alumnus Mahlangu found this out when thrown into the deep end by brassmen Stompie Manana and Teaspoon Ndelu, who simply went on tour with Richard John Smith in 1978, leaving him to figure out the horns for the Afro Pedlars by himself.

“For years I played without any trumpeter or horn player with me, except for a moment when we had Thabo Mashishi and Mfaniseni Thusi who, at some point, was the leader ye Bayete.”

Swimming in deep waters would have given Mahlangu, along with other Pelican regulars Mokoena, saxophonist West Nkosi and trumpeter Dennis Mpale, the confidence to form the short-lived Ensemble of Rhythm and Art, whose hard-driving drums, funky rhythm guitar and bold horn lines in their songs Funny Thing and Pelican Fantasy are worthy of a blaxploitation flick theme. “That was my concept,” says Mahlangu somewhat self-effacingly. “We did stuff, but it was undocumented. We were dabbling with stuff — I don’t know if I could call them compositions.”

One Night in Pelican, with tunes by Dick Khoza and the Afro Pedlars, Ensemble of Rhythm and Art, Spirits Rejoice, Makhona Zonke Band, Abocothozi, The Drive and others, joins the dots of the stories lurking beneath the surface of the Pelican legend. Told by semi-reliable witnesses, these are stories that almost slipped from view but are now reanimated by the music. Contained herein are sounds they would have heard, helped to create or promote by participating in an environment in which they were being workshopped and, ultimately, thrived, however fleetingly.

One Night in Pelican: Afro Modern Dreams 1974-1977 (Matsuli Music) was released in 2021. Kwanele Sosibo’s liner notes were commissioned by the label, and appear here, in edited form, with permission