South African actors John Kani (left, as 'Creon') and Winston Ntshona (1941-2018, as 'Antigone') perform at the final dress rehearsal of the Market Theatre of Johannesburg/Royal National Theatre revival of Athol Fugard's 'The Island' at the Brooklyn Academy of Music Harvey Theater, Brooklyn, New York, New York, March 31, 2003. Kani and Ntshona co-authored the play with Athol Fugard in 1973. (Photo by Jack Vartoogian/Getty Images)

South Africa’s formal theatre tradition dates back to the 1830s, when Andrew Geddes Bains’ Kaatje Kekkelbek was performed in 1838 by the Grahamstown Amateur Company. In South Africa, the artform came into its own during the apartheid years, particularly the protest theatre of the 1970s and 1980s.The South African Cultural Observatory’s Covid-19 impact report indicated that performing arts was the most vulnerable of all the cultural sectors. As a result of the lockdown, theatres were closed or running at limited capacity, leaving artists without income for a substantial time.

Other problems are a lack of audience development caused by the inaccessibility of theatre spaces for ordinary South Africans, a lack of early exposure to theatre in the educational system, declining media support and a lack of marketing that speaks to specific target audiences.

In his book, The South African Consumer Landscape, Paul Egan writes how working-class South Africans account for 25% of the share of the country’s consumer income, which translates to R520-billion a year. One could argue that the South African economy is carried on the back of the working class. The working class’ wages account for the biggest market share of consumption, which translates into billions of profits for companies. What these companies have successfully done is to look beyond stereotypical views of the working class — which can be characterised by the title of the Mbongeni Ngema’s play Asinamali — but rather look to them as people who can afford goods and services that can dance to the rhythm of lives.

Another group of people, who could be characterised by the Zakes Mda play, The Mother of All Eating, are cash cows to big corporations that have milked millions by creating goods and services that speak to their aspirations and desires.

What theatre needs to be sustainable is to find its way into the hearts and, most importantly, the wallets of these two groups. The department of sports, arts and culture’s 1996 White Paper on arts, culture and heritage places more emphasis on theatre being a tool of social cohesion and nation-building than it being a tool for job creation.

However, with recent updates to the White Paper, in particular the 2017 version, one sees theatre transcending the strategic vision of social cohesion and nation-building to become an economic site for job creation, investment opportunities and economic growth. An example of this is how the White Paper states “subsidised playhouses are required to generate revenue at a minimum of 40% of their return on investment on their production costs through box office, sponsorship and other income-generating activities”.

Strategic investment needs to happen on how to transform our stories embodied in theatre form into gold that we can cultivate, refine and take to the world. Theatre spaces need to be rigorous in their approach to how they become economic drivers and enablers for economic growth.

Susan Bennet touches on this in her essay Theorizing Globalization through Theatre (2005) by looking into how cities could become sites of cultural production, whereby the theatre forms part of the ecology, where investment in the tourism sector feeds back into the theatre sector.

“Through case studies of theatre and theatricalisation in New York City and Las Vegas, ‘Theatre/Touris’ explores how cultural practices have been harnessed as a powerful marketing strategy in the branding of cities, and how this has impacted the nature and reach of theatrical production. For this reason, corporate entertainment interests have increasingly understood the value of the tourist spectator and have developed theatre products to underpin a complex tourism ‘ecology’.”

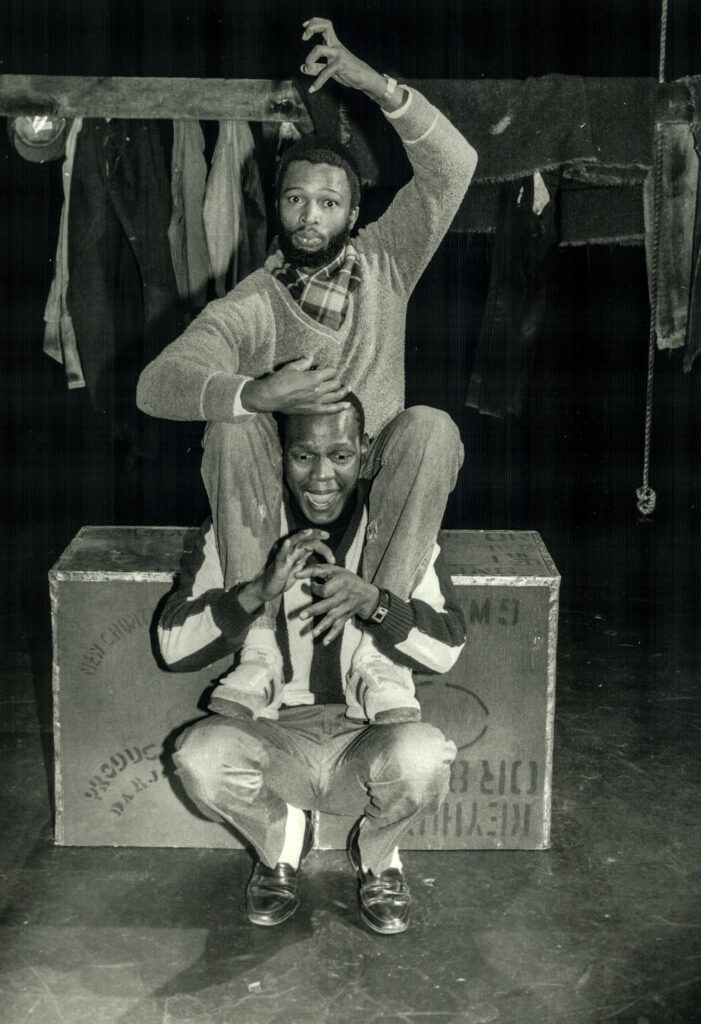

Puckish humor: Sello Make; top; and Louis Seboko; stars of Woza Albert!; currently at Toronto Workshop; take humorous digs at Pretoria’s white rulers in their two-man play. (Photo by Frank Lennon/Toronto Star via Getty Images)

Puckish humor: Sello Make; top; and Louis Seboko; stars of Woza Albert!; currently at Toronto Workshop; take humorous digs at Pretoria’s white rulers in their two-man play. (Photo by Frank Lennon/Toronto Star via Getty Images)

Theatre spaces evolve into tourist attractions. An example of is The Market Theatre in Johannesburg, which forms part of the culture precinct of Newtown.

One of the ways it can begin to do that is through audience development. To a certain degree, it is a myth that people don’t have money. But they are certainly specific about where they choose to spend their money.

Theatre suffers from the stigma of being a elite art form due to how early exposure remains accessible to a privileged few. Even in the communities in which theatre spaces are found, locals often don’t feel like custodians of the institutions.

Yet the past is very different. Protest theatre had the ability to transition from local community halls to mainstream stages while also cultivating an audience locally and abroad.

An example of this could be seen in how protest theatre productions such as The Island, Woza Albert! and Sarafina continue to be re-staged, drawing in large audiences.

The production The Island by Dr Jerry Mofokeng wa Makhetha recently toured the Free State and the Northern Cape. During one performance where load-shedding hit, the audience refused to leave the venue, lighting the stage with their phones.

Although we no longer live under apartheid, we still grapple with socioeconomic conditions that derive from apartheid. Contemporary theatre makers are still struggling with a commercially viable formula that speaks to these challenges.

Some ingenuity was displayed in how different theatre spaces reacted as Covid-19 attempted to take theatre “towards an empty space ”. Some theatre spaces and festivals went with the option of streaming their work, while the State Theatre took its shows (Marikana the Musical, Freedom, Askari, Shaka Zulu: The Gaping Wound and Silent Voices) to Ster-Kinekor’s big screens. This strategy allows for theatre to have a secondary audience and income stream.

This ingenuity has ignited an interesting debate on form and the possibilities for the future of theatre. Loyalty programmes in theatre spaces, such as the State Theatre’s sales ambassadors programme, can be considered.

Encouragingly, while doors of other theatre spaces have shut down, others have opened up, such as the Tx Theatre in Tembisa and The Shack Theatre in Khayelitsha.

The road to more audiences is full of dramatic twists and turns but a worthwhile one because story is a way of making sense of the world.

This article was produced as part of a partnership between the Mail & Guardian and the Goethe-Institut, focusing on sustainability and the arts