Renowned Sbongile Khumalo inducted Brenda Sisane ‘into that place of women’. Photo: Siphiwe Mhlambi

Two decades ago, a roll-call of South African jazz musicians would have included a number of women — Sibongile Khumalo, Judith Sephuma, Gloria Bosman, Miriam Makeba, Sathima Bea Benjamin, Thandi Klaasen, Abigail Kubeka, Dorothy Masuka and Dolly Rathebe. That list grew to include Melanie Scholtz, Zamajobe, Nomfundo Xaluva, Omagugu Makhathini and more during the latter part of the 2000s.

But in the past decade, there has been a decline in the number of women in South African jazz, which has created a need for a separate category — women in South African jazz.

It’s this title that I have been grappling with — what does it mean and why is the delineation “female jazz musician” necessary? Could there be alternative approaches that expands our understanding of women’s place, which would influence how we talk and write about, and view the role of women in the creative economy that includes jazz?

Brenda Sisane, who until December last year presented The Art of Sunday on Kaya FM — an enclave for lovers of jazz, jazz-leaning and experimental music — proposes this.

“We need to find new words and verbs to describe the power and the strong contribution. There are more things [in] the ecosystem of music. Women fill in those gaps when they walk into the space of artistry, [and] we don’t talk about [that], we don’t write about [that],” she says.

Sisane, who also does advocacy work for International Jazz Day in South Africa, asserts that women don’t just walk in and spend their time on stage. They are present backstage, they are front-of-house, they are other things besides being on the bandstand.

She uses the example of pianist, songwriter and producer Nomfundo Xaluva, saying that she is among the very few women artists “taking up [the] opportunity to come and speak about the importance of art in politics”.

“It takes something for you as a woman, as an artist, to believe that, and then do a study on Miriam Makeba, and stand up and speak about why [her] story needs to be told properly,” she says, referring to Xaluva’s masters thesis on Makeba, which provides “an analytical musical perspective” that is missing from the many documents about her life story.

“You can see how Miriam as a singer [and] musician par excellence, then director, businesswoman — you can see how her story is peppered by the names of men around her: the men that rejected her, the men that dumped her, the men that broke her down. The narrative and the language of women’s place in music has to change.”

A shift in discourse

Titi Luzipo — who once organised a tour on which she performed songs from the songbook of her mother, Vuyelwa Qwesha Luzipo — addresses this singular occupation of multiple positions.

“Being an independent musician means that you are a company with all the different departments. One thing I learned from the tour was the importance of documenting your ideas,” she says.

Her mother came of age in the 1970s as the lead vocalist for The Soul Jazzmen, which featured greats such as Zim Ngqawana, Winston Mankunku Ngozi, Feya Faku and Tete Mbambisa. She is the essence of musical royalty, operating in the same lane as Cape Town’s Sylvia Mdunyelwa.

Like Sisane, who credits Khumalo with inducting her “into that place of women”, Titi’s approach found comfort in knowing that women such as Sephuma were on her side.

“She was coming for a show in PE [about 14 years ago]. She was looking for a local artist who was going to curtain-raise for her show. My name was then submitted, and she just loved me.”

They have kept in contact since, with Sephuma playing the role of adviser during Luzipo’s years at university and through to when she organised her own shows.

Supporting roles: Jazz and Afro-pop singer Judith Sephuma has acted as Titi Luzipho’s. Photo: Siphiwe Mhlambi

Supporting roles: Jazz and Afro-pop singer Judith Sephuma has acted as Titi Luzipho’s. Photo: Siphiwe Mhlambi

This common ground of belonging that is facilitated through mentorship creates safe spaces for other women to find their footing. This is perhaps what has been happening over the past decade — the new musicians are being nurtured.

I contacted Siya Makuzeni, to hear her side regarding how the transformation of the live music scene in Johannesburg over time has affected her career, because she was active during the time period I’m interested in.

She starts by noting the changes in the jazz scene.

“I think we went through a bit of a …” she pauses to carefully consider her words, “I don’t know, that period was a little bit concerning for everyone, around the early 2000s when it just seemed as though things were starting to die down. We had a lot of different things take place. The Bassline closing down was, for me, a way of being able to see what I’m talking about. Although people did their best to try to kind of keep it going, perhaps it was just something that needed to happen at that time.” She then notes that a new generation mushroomed from that initial collapse.

“I think that that’s what we’ve gone through now. The younger generation came and stamped their mark and definitely made their voice known, and you can hear these nuances in their music.

“But I also think [that] we’re doing another dip. It’s weird. Musical scenes are very strange. Somebody will figure out a formula, and then once it picks up, suddenly you’ve got a thousand copy-cats. I don’t think it’s anyone doing anything deliberately, it’s just perhaps natural. I don’t think it’s going to die down this time around; I just think that we might have a situation where there’ll be a lot of weaning out. Those who have original voices, I think this is the time for them now.”

With this statement, Makuzeni reignites my awareness that we don’t always view any one situation in the same way, and that there are views one may not be considering. Writing about these observations is a way to think through any bottlenecks in the thoughts that inform our actions, be it in music or in life generally.

Makuzeni started out in jazz, but she has been aware from the onset that it’s not a box she would like to inhabit all the time. Throughout her high school years she was learning the art of composing songs.

Siya Makuzeni sees shifts in the jazz scene and believes those with original voices will survive. Photo: Siphiwe Mhlambi

Siya Makuzeni sees shifts in the jazz scene and believes those with original voices will survive. Photo: Siphiwe Mhlambi

Maledom abounds

Gabi Motuba takes a leaf from this; she wears many hats — vocalist, composer, arranger, conductor and experimental musician.

Sisane sees her as someone who is doing their darndest to not be in the shadows.

“And I’m not saying she considers being with [ her husband Tumi Mogorosi] as being shadow; they seem to have an incredible relationship — but you can see that she’s important to him as an individual with her own ideas,” Sisane says.

Motuba has recently completed a residency at the Soweto Theatre, and proceeded to present her five-movement string project called The Sabbath during this year’s National Arts Festival in Makhanda.

During the online launch of the Indaba Is (2021) compilation, she spoke to the London-based writer, researcher, radio producer and host Teju Adeleye about her departure from traditional jazz norms through projects such as The Wretched, noting: “In terms of being a jazz artist, I was critiquing this very traditional space of ‘jazz artistry’, ‘jazz vocalist’, and also the aspect of ‘scat music’. I was pulling away from that and trying to explore other avenues, trying to see where jazz would lead me.”

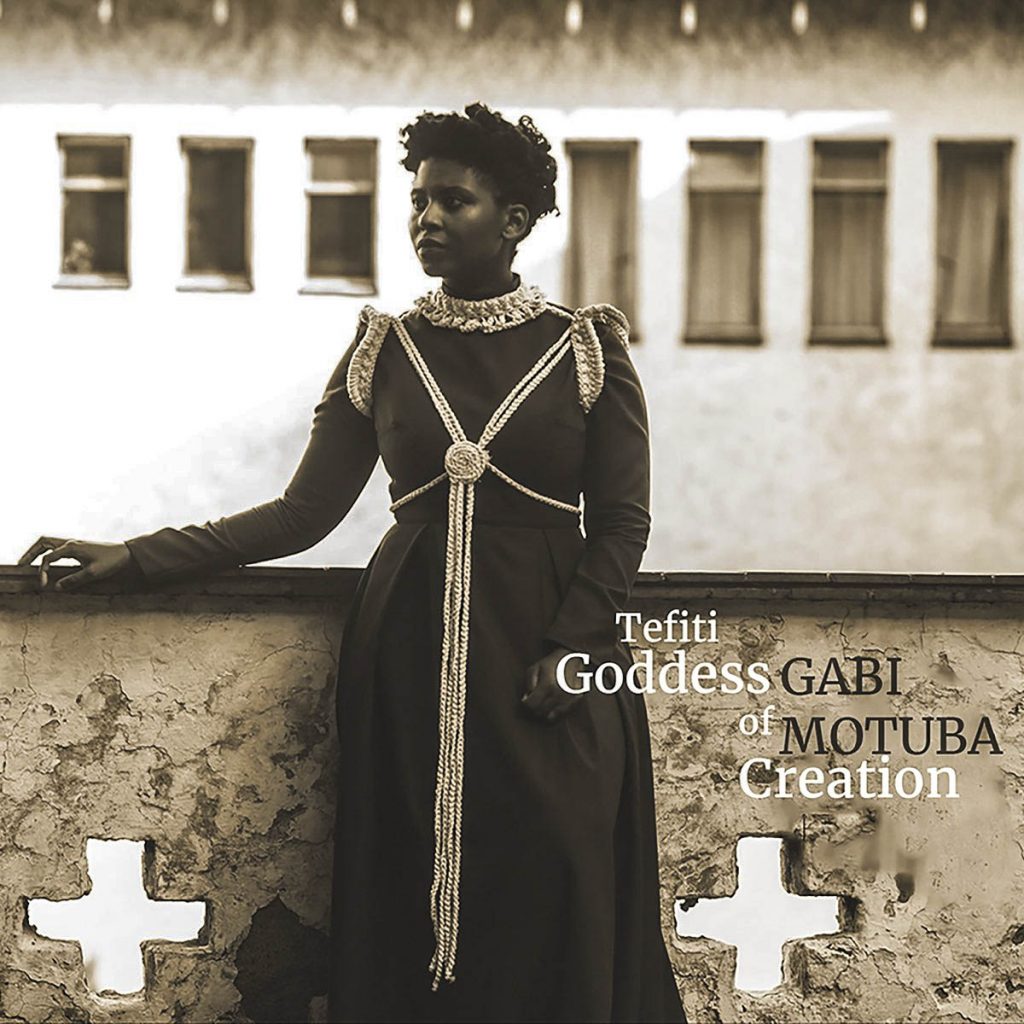

Motuba made a point similar to those she made in an article written by Gwen Ansell for New Frame: “In Tefiti [Goddess of Creation], I was exploring new ways of thinking through jazz, in terms of sound and how curious it is for female jazz musicians to have to see their sound through male musical models. I can’t separate my creativity from my body, and yet that’s how it’s taught.”

Tefiti, Goddess of Creation (2019) is the illustrious string quartet project which precedes Sabbath. (Te Fiti is the Polynesian goddess with the power to create life.)

“My experience in that space is one of dissonance: I hear other sounds than those heavy, rhythm-accentuated ones. Women are part of the music workforce — and yet even that idea of ‘workforce’ is imaged as male. The genre boxes are toxic; expression can’t be standardised like that,” says Motuba.

Her aim with The Sabbath is to relegate all that doesn’t resonate with her concept of jazz, which she says is ultimately what stifles the roles women play in the music.

Motuba’s statement is in line with Sisane’s, who notes the enduring male-centrism of South African jazz.

“There is something very male-dom that thrives within the scene. Even the young cats, they move as packs among themselves. Hence I mention [Thandi Ntuli] because I see her in an outfit such as The Rebirth of Cool with Kenzhero and them, and then I see her in Indaba Is and the big role that she’s played and I’m like, what does it take to be that? Makes me ask what happened to Nomvula Ndlazilwana. What prevented her from shining because she and [Bheki Mseleku] were in tandem as young lovers.”

Gendered genre: Gabi Motuba plays many roles in the jazz scene, from vocalist and composer to arranger, conductor and experimental musician.

Gendered genre: Gabi Motuba plays many roles in the jazz scene, from vocalist and composer to arranger, conductor and experimental musician.

I contacted pianist, composer and arranger Nobuhle Ashanti about how she saw her place in jazz. The Cape Town-based musician has been gigging on the city’s circuit for a few years and is now ready to introduce the greater world to her forthcoming debut album, due for release towards the end of this year.

To Ashanti, as to someone such as Ntuli, it’s the “texture” of people, and not their sexual identity, that influences who she chooses as collaborators.

“I always, first and foremost, look at a person and I’m, like, can I have a conversation with you? Do you reel me in, do you intrigue me, do I want to learn from you?” says Ashanti. “My band is my safe space, it’s my little tribe, it’s my home, and I want to make it a home for the right people.”

Regarding the music she makes, Ashanti says that it references her Cape jazz roots, specifically the melodic meanderings of Robbie Jansen, while also pulling away to find something new. “It’s a bit scary, but that’s what’s happening right now,” she says.

I started this story hoping to find clean-cut answers, such as the demise of record companies like Sheer, or venues like the Afrikan Freedom Station and The Orbit in Johannesburg. Instead, answers brought more questions. It’s this uncertainty that may contribute to an increased awareness of how things are, if not a solution.

Nobuhle Ashanti focuses on the ‘texture’ of people and not their sexual identity when choosing who to work with.

Nobuhle Ashanti focuses on the ‘texture’ of people and not their sexual identity when choosing who to work with.