Getting the Ballen-ce right: Hungry Dog. Photographer Roger Ballen believes that the formal qualities of a photograph are vital.

When Roger Ballen first came to Joburg, in 1974, he stayed at the YMCA in Braamfontein. At the time, he was a 24-year-old New York existentialist, most of the way through a voyage from Cairo to Cape Town.

That night, as Ballen sat in the hostel’s lounge, a fellow guest slit his wrists and bled to death. After that welcome, most travellers would have fled to Cape Town without delay, but Ballen stuck around for weeks, met his future wife, and eventually returned six years later to make his life in the city.

Ballen has an unusually high threshold for darkness. Joburg, despite its surfeit of sunlight, has darkness to burn. And Ballen is still here, at 72, burning it.

The world-renowned photographer’s new retrospective show at the Standard Bank Gallery, In Roger Ballen’s Johannesburg, curated by Dr Same Mdluli, is an astonishing trip through some of his best work since 1994, when he began to make images in the metropolis.

While all the photos and drawings were shot or made in the city, they are not really of the city. They are of the shadowlands of Roger Ballen, and they threaten to lead us into our own shadowlands if we give them half a chance.

Given that Joburg is essentially a concrete wound in a plateau, a living scar of the urge to dominate and ravage and accumulate, it does echo some of the psychodramas that preoccupy Ballen. But he is far less interested in the city itself than in the dreamworld that rustles behind and beneath it.

Conversation, 2003

Conversation, 2003

Ballen’s material has shifted through the decades — from defiantly strange and vulnerable human subjects to living and/or dead animals to assemblages of haunted objects (mannequins, masks, stuffed beasts), to ferocious drawings of apparitions. But, throughout those phases, the photographs are always stage sets for unspeakable, deathly plays — plays that have either just finished or are about to begin. The actors are both dead and alive. The sets echo faintly.

Ballen’s eye is primal, uncanny and ungovernable, despite its deep aesthetic refinement. It’s an eye that denies ease, both to us and to himself. Despite his almost total lack of political intent, he threatens our peace.

His reward for all this spectral disturbance has been plenty of flak, along with plenty of adulation.

“I am now totally immune to critical responses,” he says. “After 54 years, I’m battle-hardened.”

Ballen is tall and upright, with a lugubriously regal face and a sonorous Manhattan baritone. He speaks with professorial seriousness — until he cracks a joke and breaks into a disarming schoolyard giggle.

“I’ve put in my time, you know,” he says. “I really have. Fifty-something years of this work — of being obsessed with it. Ups and downs. In the beginning, it wasn’t easy. For a long time here in South Africa, back in the 1990s, I wasn’t very popular, with the left and with the right.

I always joke that my only friend was my dog, Leroy.”

At the time, his early photographs of poor whites, in the books Dorps and Platteland, were castigated as exploitative. But, for Ballen, that discomfort was simply a projection of an evasive refusal to witness pain or difference. In his vision of artistic morality, to “aestheticise” suffering is simply to recognise it.

As he writes in the catalogue: “The people I work with are outsiders. They live on the edge, accept life for what it is, and realise there is nothing they can do to change things. They are at the mercy of the forces they cannot control. They wear no mask. What you see is what you get.”

Strange sites: One Arm Goose

Strange sites: One Arm Goose

Ballen has remained part of the lives of many of his subjects and collaborators (his models often draw on surfaces in the scene) and he supports many of them materially.

“I’m happy to be able to help them in any way I can. There’s an interesting comment that captures the hypocrisy in the art business — sometimes I’m asked, ‘Do you pay these people?’

“So what am I supposed to do? Let them starve? Not pay for their children’s education? They help me in all sorts of ways and then I don’t pay them? What kind of logic is that? I guess the idea behind this question is that it has to be some sort of spontaneous event; that you don’t realise that you’re part of the picture.”

It’s too easy for elites to flinch from the troubling spectacle of abjection, he says.

“You can easily hide from darkness in any city in the world. Even if you’re in Baghdad. You can hide from it in shopping malls, you can hide from it in suburbs, if you’re economically well-to-do. Many people don’t cross the physical and psychological boundary line here in Johannesburg, don’t have any interest in doing so.

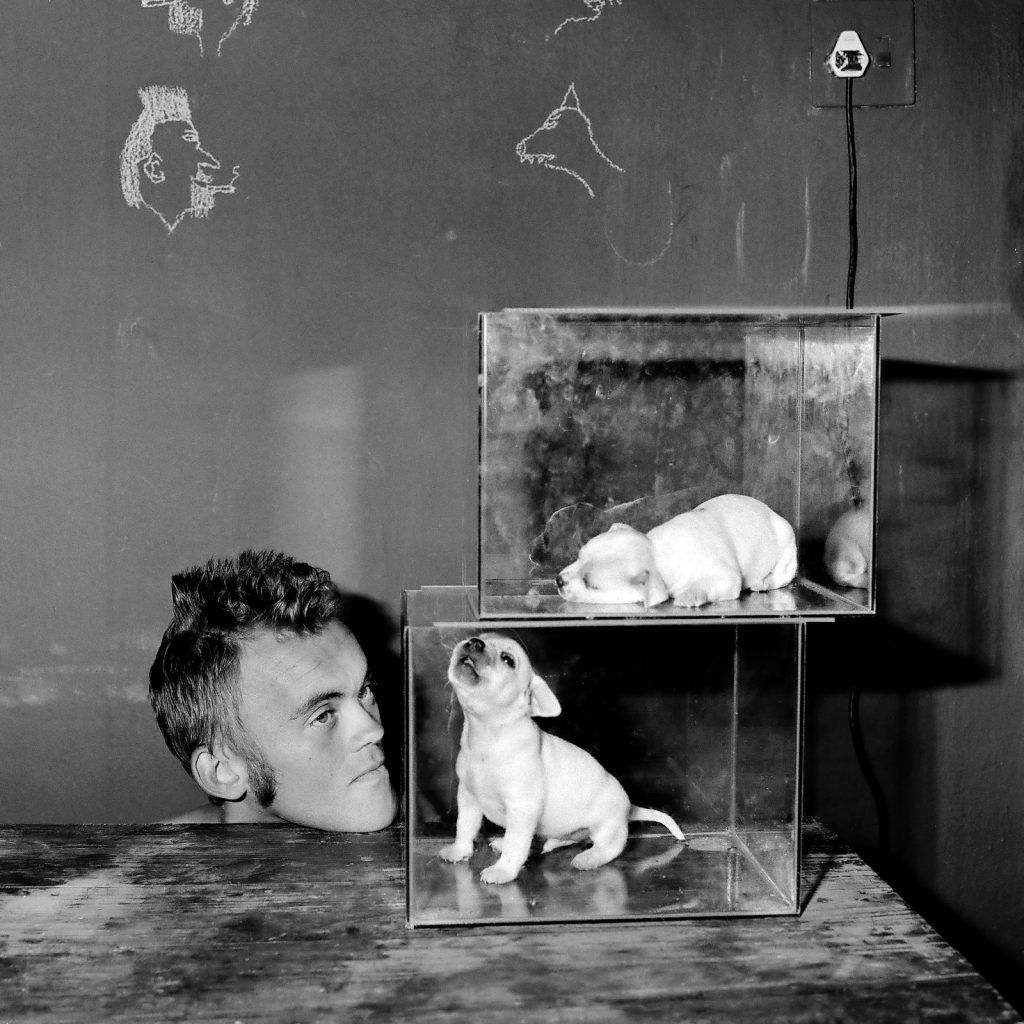

Puppies in Fishtanks is typical of Roger Ballen’s interest in setting a stage and capturing the shadow world behind Johannesburg where his photographs are taken.

Puppies in Fishtanks is typical of Roger Ballen’s interest in setting a stage and capturing the shadow world behind Johannesburg where his photographs are taken.

“But, for me, it’s always been an interest to cross that line,” he says. “To try to find this other zone: the fear zone. Then you’re getting deeper. You’re coming into contact with your instinctual nature in some way or another. This is not what most people are trying to do.”

In 2012, Ballen’s collaboration with Die Antwoord on the music video for the band’s I Fink U Freeky allowed his mordant aesthetic to erupt onto the global pop-culture stage.

“That video just blasted it off. It’s gotten 180-million views or something. And so many young people got to know my work through it, which was really great — people would never otherwise have come into contact with fine-art photography.”

But despite his appreciation for the virality of the internet, he has a beef with contemporary visual illiteracy, which he sees as linked to the flooding of our eyes with visual noise.

“Sometimes there’s a block against trying to confront the picture on its own level. A lot of people who like art, who see art, who experience art — still can’t see the visual dynamics of the work. They have to always encapsulate it in words. If they can’t find the word for it, then they just can’t understand it. It’s too complicated. ‘It’s beyond me,’ they say.”

The ease of photography exacerbates this plague of visual and interpretive laziness, he says.

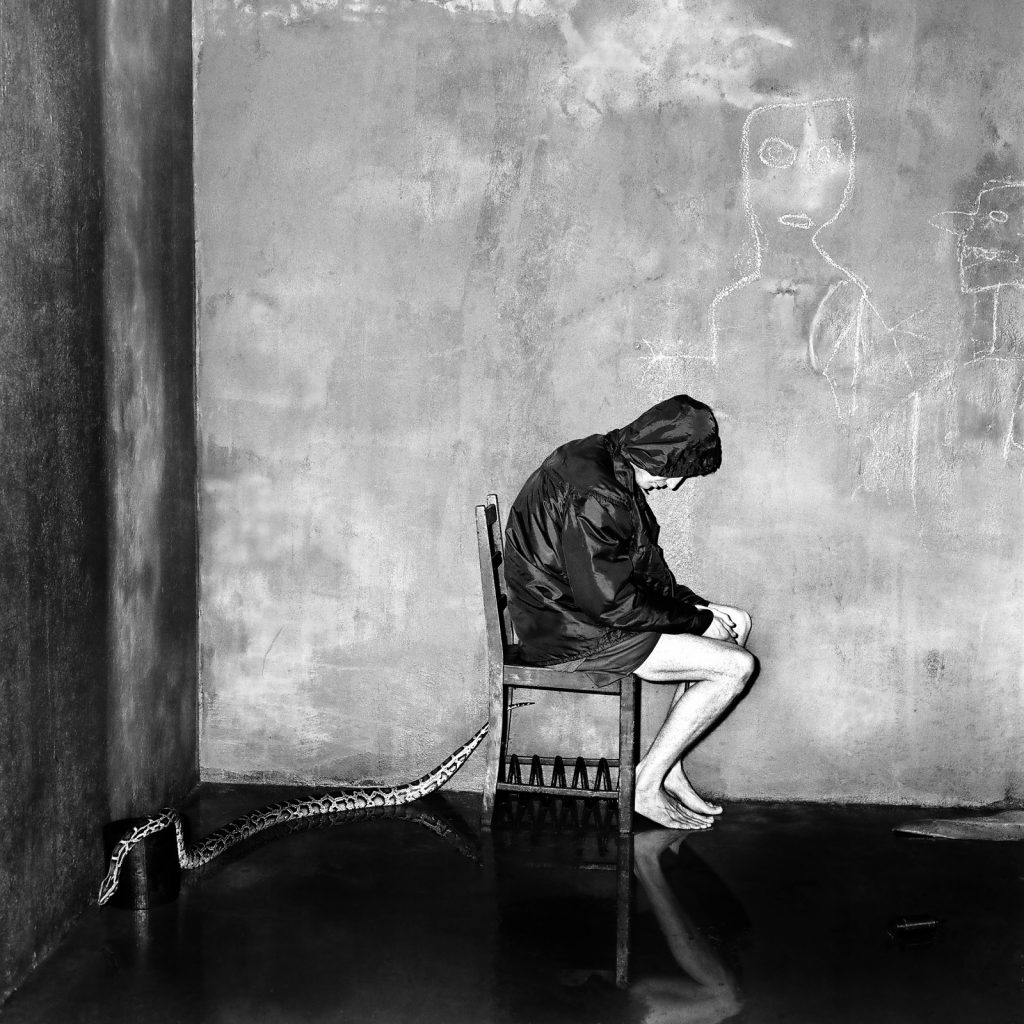

In black and white: Uneaten, 2003

In black and white: Uneaten, 2003

“If you look at my photos, every picture is formally perfect. You can’t find any mistakes in them. They have a psychodrama that comes at you, but one of the reasons it can come at you is because the formal qualities are organically working towards a purpose. Without that it doesn’t work. It just breaks apart.

“This is such a problem in photography — people are subject-orientated. They see something, and think, ‘Oh, look at that!’ and take the picture but they forget to look at the flare on the floor. And they’ll never get the picture right with a flare on the floor.”

His obsession with the rigours of the form dates back to childhood, when his mother started a photography gallery. Images by Henri Cartier-Bresson and Andre Kertesz surrounded the young Ballen.

On graduating from high school in 1968, his parents gave him a Nikon Ftn camera.

“I was immediately able to take good pictures. When I was 18, I was able to take pictures that I’m still happy with. I never took any courses. You learn from your pictures. Anybody can look at the books, the museums — but then you have to go out and take the picture.

“So where are you starting? Where’s the string? You gotta find the string. Sometimes it leads you to dead ends, then you got to go back and try to find another string. You’re finding your way through this myriad of doors. Most of these projects end up taking me about five years. It’s not easy to take good pictures.”

Bitten, 2004

Bitten, 2004

One of his early projects was to document the Woodstock festival in 1969: “I heard that it was going to happen at an upstate farm owned by a Max Yazgur and I knew the name. Turned out his brother was my dog’s vet. So, I thought maybe I’ll even meet him up there, because I liked the vet. I didn’t realise there’re gonna be all these people out there.”

At the time he was studying psychology at the University of California, Berkeley, where he absorbed ideas that still guide his vision: RD Laing, Carl Jung, the Theatre of the Absurd, Sartre, Heidegger.

In 1973, he spent five months painting at the Art Students League of New York, incubating an impulsive “art brut” line that would infiltrate his photographs decades later. At the time, his teacher told him his work “belonged in the Stone Age”.

Next came the fateful Cairo to Cape Town trek, followed by another one, from Istanbul to Papua New Guinea. Having met Lynda Moross in Joburg in 1973, he returned there to marry her in 1980 — after studying geology at the Colorado School of Mines. Then, by working as a prospector, he had a pretext to chart and mine the visual metal of apartheid South Africa. Eventually, he banked enough money to get on the hamster wheel of full-time photography.

“The worst thing about taking good pictures,” he says with that mischievous giggle, “is that you have to try and start another one. It’s over now. You won the race. Now you got another race.

“I’m not taking pictures for the other,” he says. “I don’t deliberately try to challenge other people, or make people anxious, or make people happy, I don’t even begin to think that way.”

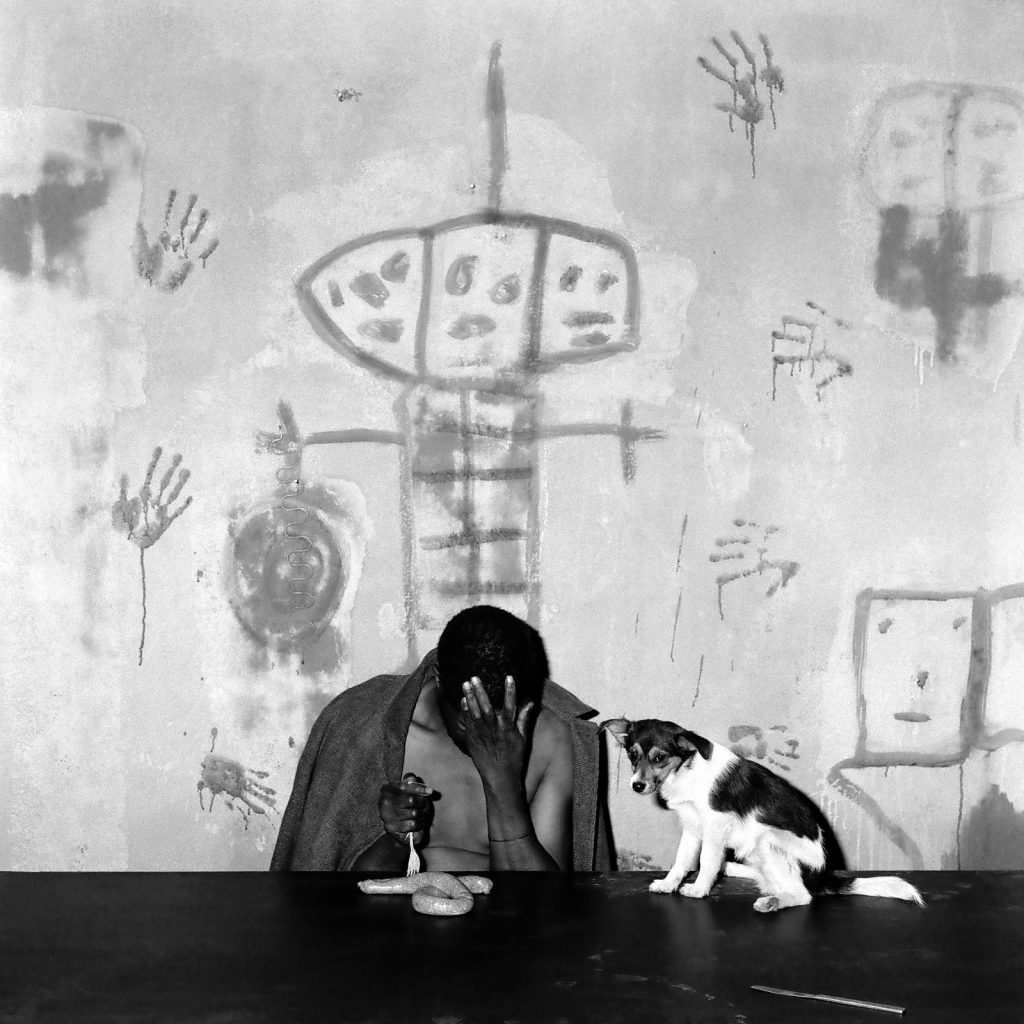

Open Up, 2013. Roger Ballen’s photographs often contain strange and vulnerable human subjects and living or dead animals and his models frequently draw on the walls.

Open Up, 2013. Roger Ballen’s photographs often contain strange and vulnerable human subjects and living or dead animals and his models frequently draw on the walls.

“Each picture is a part of a piece in a puzzle that has infinite pieces, and you try to put them all together. And when you look back on your life, you’re happy you did it because it helps you to understand your experiences a little better. This is a Roger Ballen diary,” he says, gesturing at the exhibition. “That’s the best you can do. What else can you do?”

In Roger Ballen’s Johannesburg is on at the Standard Bank Gallery until 31 January from 8am to 4.30pm on weekdays and 8am to 4pm on weekends. Entrance to the gallery is free. Standard Bank Gallery, corner of Simmonds and Frederick streets, Johannesburg.