Bound: Black men arrested for being in white area illegally. Photo: Ernest Cole

Growing up during apartheid, my parents never talked much about politics at home in Pimville, Soweto. As the breadwinner, my father spent long hours as a bus driver transporting passengers in the City of Gold to put food on the table and give shelter to his large family of six children and his wife.

Our modest four-room house in the new section called EmaSix-Thousand in Zone 4 was later renovated into a big house. However, a few blocks away from our house was a section where many struggling kids lived in old houses. As children, we played together without discrimination, and did not stress about the fact that each section/zone was divided according to different tribal groups.

Even though life was simple, I knew that something was not right.

My siblings and I attended the local government schools which offered Bantu education. It was at these learning institutions that I was later conscientised about how Bantu education was designed for servitude. During science class, we did chemistry without chemicals or tools. Many teachers used corporal punishment on pupils.

Meeting Ernest Cole

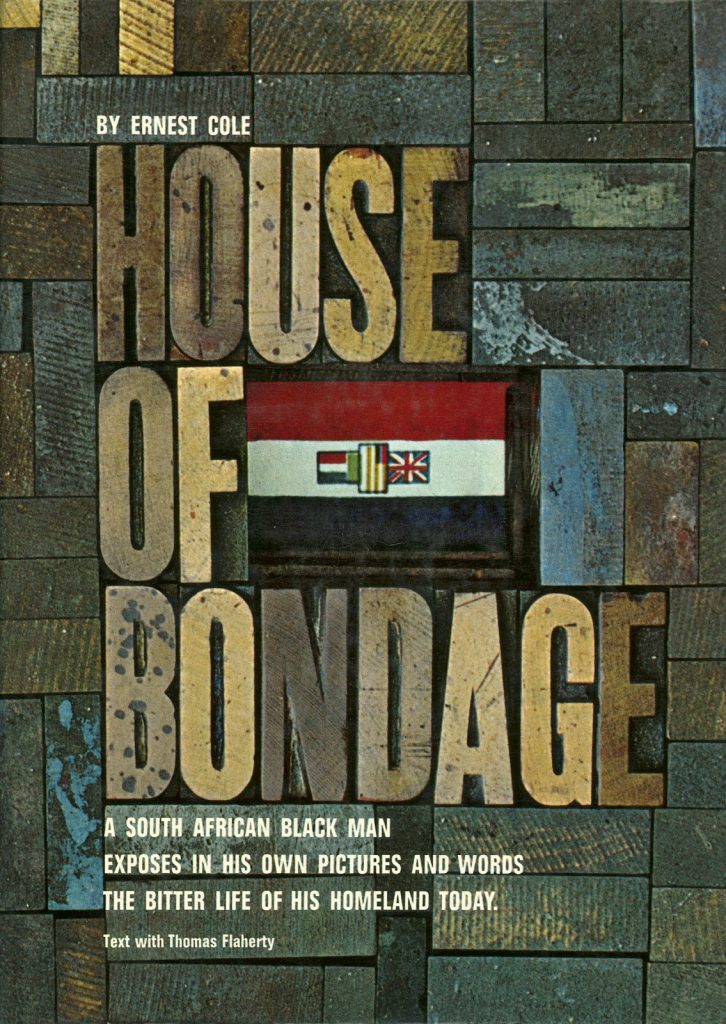

As a young adult, I thought I’d seen it all until I came across the House of Bondage by critically acclaimed photographer Ernest Cole. I was a student at the Market Photography Workshop (MPW) doing a beginner’s course in 1998. The book was first published in the United States in 1967 and was banned in South Africa, however, a few copies were smuggled into South Africa, making it a rare book to find or own.

Kept inside a locked cupboard, House of Bondage significantly opened my eyes to the brutality that was taking place at a broad scale in this country. The powerful and haunting photographs of naked men standing in line with their hands held up in the air, waiting for medical examination; or of a mine kitchen helper dumping food on men’s plates with a shovel; or of a young squatting boy inside a packed heated classroom with sweat running down his face. Images of segregation in public places and transportation used to dehumanise the African people were shocking to me.

Cole’s images evoked in me a sense of belonging and understanding of who I am and how my situation and thoughts were shaped by the ferociously racist system. I resonated with his work and how he also eloquently narrated the stories of each topic that he covered, so that it made sense for everyone to understand.

His work gave me the courage and wisdom as a young photographer to understand the power of a camera and words.

As a freelancer, I use both words and images to put my ideas and messages across. I managed to get myself a second-hand copy of the book after 20 years of intense search, and it is kept safely at home.

Cole was born in March 1940 as Ernest Levi Tsoloane Kole and left school at 16 when Bantu education was introduced. He managed to complete Grade 12 through correspondence. In 1958, he worked at Drum magazine as an assistant to Jurgen Schadeberg and met stellar photographers including Alf Kumalo, Bob Gosani and Peter Magubane.

After Drum, and completing a correspondence course with the New York Institute of Photography, he freelanced for various publications. In 1959 he was profoundly inspired by Henri Carier-Bresson’s book People of Moscow and he knew then that he needed to compile a comprehensive visual account of life in South Africa from his perspective.

He outwitted the Race Classification Board by changing his surname to Cole and was re-classified as coloured, which allowed him to gain access to places that he could not before. To photograph in difficult spaces, he would sometimes hide his camera in sandwich paper lunch bags and shoot through a tear. Politically, it was no longer safe for him. In 1966 he fled and later settled in New York.

Black and white: An earnest boy strains to follow the lesson in the heat of a packed classroom. Photo: Ernest Cole

Black and white: An earnest boy strains to follow the lesson in the heat of a packed classroom. Photo: Ernest Cole

The relaunch

Nonhlanhla Kumalo came into contact with Cole as a child at her parents’ home in Diepkloof.

“I suspect I met him through random photographs that I mistook for my father’s, but my proper introduction to him was through his book House of Bondage that I came across in our book collection,” says Alf Kumalo’s daughter, during the relaunch of the book in November at the Wits Art Museum.

The revised book, published by Aperture, includes unseen images under the section Black Ingenuity that examine the possibilities of black cultural production while also mourning the apartheid suffocation of such spaces.

The momentous launch was an opportunity to celebrate and shine a light on the legend. While in exile, and after the book was published, Cole received a grant from the Ford Foundation to undertake a project looking at black communities in the United States. That work was never delivered to the foundation, exhibited or published.

No one seems to know what he did with the images; however, when he died at a Manhattan hospital at age 49 from pancreatic cancer on 18 February 1990 — just days after the release of Nelson Mandela and following a visit from his mother and sister — information emerged that his archive was kept in a bank vault in Sweden, a country he used to visit.

In 2017, more than 60 000 of Cole’s negatives — missing for more than 40 years — were retrieved by the Ernest Cole Foundation, headed by his nephew Leslie Matlaisane. Sadly though, more than 500 archival prints worth millions of dollars are still kept in contention by the Hasselblad Foundation.

“The significance of Cole’s archive is that it is now housed at Wits Historical Papers,” Kumalo said.

She further told the curious audience that the Photography Legacy Project (PLP), which played a significant role in providing the digital photography content for the making of the book, has “digitised the best of Cole’s South African and US material” so it is accessible to the world.

Guest speaker Nozizwe Vundla said Cole still remains a mystical and unknown figure despite his widely published work. She advocated for the book to be “included in curricula at universities and high schools so that he becomes a household name”.

Professor Hlonipha Mokoena, in closing, marvelled at Cole’s writing skills, saying it ignited the fire that burns underneath each photograph.

When Cole died lonely, homeless, penniless and disoriented in New York, his body was cremated and returned to South Africa by his mother and sister. He was then given a dignified funeral on 10 March 1990. Today a tombstone inscribed Morongwe Martha Kole and Ernest Levi Kole sits proudly at the Mamelodi cemetery in Pretoria.

Cole’s unquestionable optimism that SA would be liberated came true. I hear him encouraging us to continue fighting. Aluta continua.

Free to choose: Tough talk and marijuana – some youths turn to crime rather than do menial work for white men. Photo: Ernest Cole

Free to choose: Tough talk and marijuana – some youths turn to crime rather than do menial work for white men. Photo: Ernest Cole

‘House of Bondage’ is published by Aperture and costs R1 475 at Exclusive Books.