Home is where the land is: Milisuthando Bongela has made a documentary exploring identity through her childhood in Transkei.

It is very rare to engage in visual stories that force you to look into yourself. A visual story that wakes you up from a place of slumber as you have forgotten yourself or you have not engaged yourself with so much depth.

Eight years in the making, Milisuthando Bongela completes her documentary titled Milisuthando.

The film is intense with emotion, if we are to compare it to anything, it would be a song that sounds drums and we get an occasional piano break.

Milisuthando shares some of her processes in making the documentary.

“I was always interested in finding out how I became who I am, how did I become black, am I black, where did I grow up, and what was that place like, trying to map back, trying to understand the history of our country by mapping the history of myself,” Bongela tells the M&G.

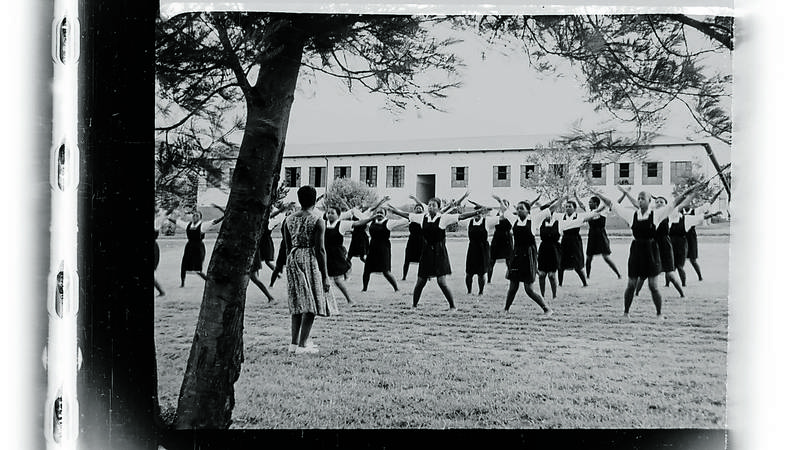

Set in past, present, and future South Africa, the documentary explores love, intimacy, race, and belonging by Bongela, who grew up during apartheid but didn’t know it was happening until it was over.

The documentary seamlessly parallels Bongela’s upbringing, and living through two different political systems.

Anchored:

‘Which forces will

you deploy as a

compass?’ asks

Milisuthando

Bongela in her

documentary.

Anchored:

‘Which forces will

you deploy as a

compass?’ asks

Milisuthando

Bongela in her

documentary.

“I grew up in the Transkei but I did not know what the Transkei was, it was just home for me. I did not know what the Transkei was politically speaking and there was a time when apartheid ended in the early 1990’s and my family along with many other families moved to East London. No one was explaining to us why we were moving or why white people were so mean to us when we got there. We didn’t have racism or race, I didn’t even know I was black as a child” she says.

Under the Bantu Authorities Act of 1951, the Transkei became, in 1959, the first region to be established as a Territorial Authority; and in 1963 it became the first Bantustan to be granted ‘self-government’, according to South African History Online.

Bongela says that she did not have a conception of what white people were and who they were because she had grown up in such a tiny world where she was accepted for who she was.

“It was only in my late twenties that at Ntate Mandela’s funeral when we were all singing a song ‘My mother was a kitchen girl, my father was a garden boy’. I was singing in the crowd but inside I felt guilty because when I think of my life, my mother wasn’t a kitchen girl, and my father wasn’t a garden boy and they used to carry briefcases to work and they used to wear high heels and makeup and they drove cars”.

Time: The film

‘Milisuthando’ will

transport you to

the past, present

and future South

Africa.

Time: The film

‘Milisuthando’ will

transport you to

the past, present

and future South

Africa.

She says that that forced her to go back to Transkei and to look at it as an adult and the more she researched and read she discovered that Transkei was a homeland, and homelands were constructed by the apartheid regime to exclude black citizens, opening the way for massed forced removals.

The documentary unpacks the history of the Transkei from her perspective, how the issue of homelands has been overlooked in our history. She forces us to think and openly talk about how the creation of the Bantu states has an implication on how those who lived in this parallel were affected.

“On one hand I am being told that I am black, a puppet, I am poor and I grew up in a township, and thinking that I grew up in a township and realising that I did not grow up in a township, I grew up emakhaya, in a homeland,” she says.

Bongela says that she realises that she did not grow up in the township but in a homeland and that experience was different from that of her friends who grew up in places like Soweto and Khayelitsha.

“You know what homelands are, you can see them on the map but discover that these places have their own flags, national anthems, their own presidents, and independent days that were contested but weren’t real this forced me to ask if my childhood was real, if this place is not real,” she says.

The difference:

Bongela says

the adults in her

world, growing up

in the 1980s, wore

high heels.

The difference:

Bongela says

the adults in her

world, growing up

in the 1980s, wore

high heels.

She says that those were some of the questions she asked herself and these questions ultimately produced this documentary. She says that she hopes the film allows South Africans to see how people influence history and how history influences people.

Bongela says that it was not one thing that moved her to make this documentary but a symphony of many things.

“I don’t want to spell things out. I want an audience that engages and picks certain themes up themselves. I am interested in what viewers pick up as they watch the film”, says Bongela.

She says that the obvious themes of the documentary are colonialism, apartheid, slavery race, racism, love, intimacy, power, fear, personal dynamics, democracy, childhood, freedom, geography, and ubuntu.

The documentary falls in and out of every theme without one overpowering another. Each theme gets its moment and is unpacked with so much respect and time. There is a break in the film where Bongela addresses white relationships in her life. She says she has an ongoing conversation with her white friends about their whiteness and how whiteness lives in them.

“It is incumbent on us to talk to our white friends in this way if we are interested in engaging and really figuring out how the next generation does not have to deal with this nonsense,” she says.

“We know that white people have got a lot of cruelty because of whiteness but it is another thing when you hear white people say whiteness is cruel. That almost means that one can enter that conversation and we can talk at a much more honest level” she says.

Belonging:

Bongela looks to

her upbringing to

answer questions

of who she is.

Photos: Supplied

Belonging:

Bongela looks to

her upbringing to

answer questions

of who she is.

Photos: Supplied

The film allows for those conversations to be had openly, honestly, and without fear.

Bongela says that after almost ten years of working on something you just have to abandon it.

“I could have gone on filming and editing but because of funds and working on something for so long, I knew It was time. Towards the end, I started getting pregnancy dreams, my got stomach got bigger and bigger, and at some point, I was walking barefoot into the hospital about to give birth and that’s when I knew that it was time to let the baby be born, I knew deep in my soul that it was time to show the world” says Bongela.

Bongela says that she likes the film to allow people to think about their own lives.

“I want people to take permission slips from the film to think about how this stuff lives in me. There are many things packed into this film, spirituality, history, take whatever you can pick up and take with you” she says.

Milisuthando will be shown at the Encounters Film Festival. Visit milisuthando.com to see where the documentary will be screened next in your city.