The King of Broken Things takes a poignant approach to being broken in a one-hander full of wonderment.

These are broken times. No more so than in Makhanda, where comedians visiting for the National Arts Festival (NAF) make jokes about the town’s ubiquitous donkeys falling into the even more common potholes.

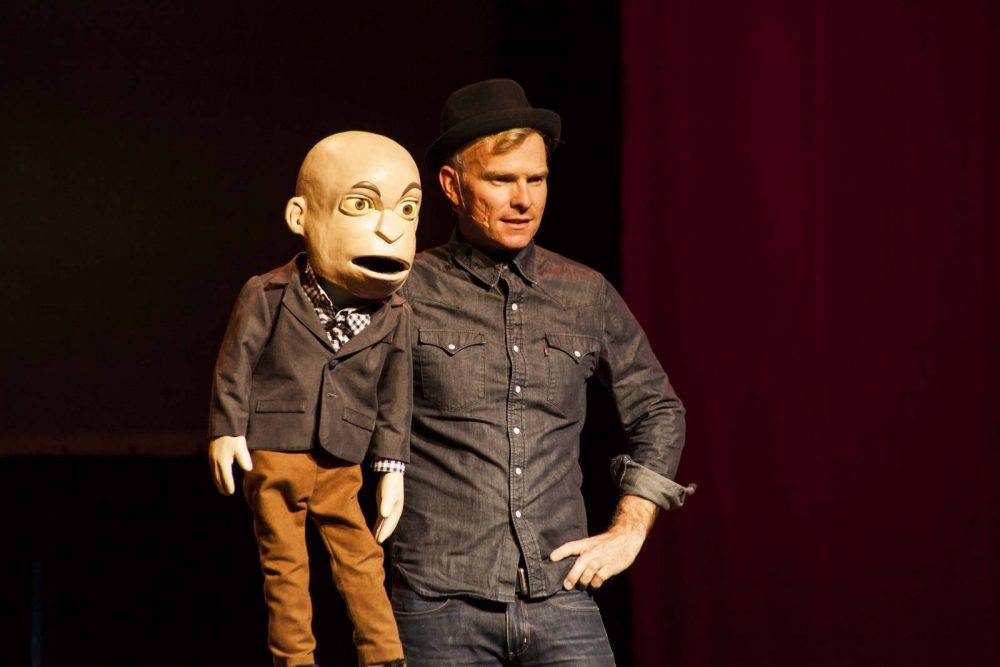

“Those are ass-holes,” observed Chester Missing, the puppet character of ventriloquist Conrad Koch during a performance of Baggage at the Thomas Pringle theatre.

Koch’s performance was more personal and less political as it dealt with anxieties through characters which included Missing; some self-deprecating humour from himself; a cobbled together Dame Edna ostrich puppet made from lurid feather dusters, a long sock and an inventively re-engineered Croc sandal harking back to Koch’s first hand-made puppet and Mr Nixon, a retired high-school teacher.

But what is broken in Makhanda, and made stark especially with the National Arts Festival in town, goes beyond mere missing tar. Like most others in the country, the municipality struggles to function. If they are lucky residents have two days without water and the next with. In the township people can go over a month without water. These are mere droplets in an ocean of failure.

A failure that extends to us remaining a country of broken people. A country where men break women, especially, was made hilariously, discomfitingly, acute during the performance of Text Me When You Arrive at the B2 Arena.

Written and performed by Aaliyah Matintela, Thulisile Nduvane and Sibahle Mangena, Text Me When You Arrive is an excoriating take-down of South African men and the society which produces these abusers and murderers of women. The actors go through a list of things women need to do everyday — like “embrace the cat-calling when you walk down the streets of Mzansi” to avoid being raped.

Chester Missing at the National Arts Festival.

Chester Missing at the National Arts Festival.

Using frenetic satire, they weaved the banal, yet perilous everyday (like taking taxis to work) with real experiences of the country’s entrenched rape culture.

The trio perform formidably — capturing wonderfully the leery swagger and unmasked menace of men on the streets, whether in Johannesburg or Lephalale.

All three performers were energetic but maintained perfect timing to ensure the satirical punches in the script landed. People laughed without losing sight of the abhorrent reality of the subject matter. The acting was pitch-perfect.

The King of Broken Things takes a poignant approach to being broken in a one-hander full of wonderment. Material things, metaphorical hearts, a discarded flask which is transformed into a vase and a magical cape made with “light” words (like “believe” and “dream”) are just some of the things the play’s young protagonist considers as he longs after a father he hopes will return.

Cara Roberts is superb as the pre-teen boy, teased by his classmates for his obsession with repairing broken things. Considering Kasa-Obake (Japanese folklore about old umbrellas returning as ghosts after a century), the young scientist-inventor says he likes to repair things because he thinks “it’s worth it to carry on with the scars to show what we have been through”.

An incisive observation with contemporary relevance from a young boy with an old soul in a carefully staged and performed play that is smartly written by director Michael Taylor-Roberts.

Certainly, in these broken times, The King of Broken Things is an essential reminder that human good and hope can prevail if we remember how to dream.

*The King of Broken Things is at the Victoria Theatre at midday on 30 June, 1 July and 2 July. Baggage is at Thomas Pringle on 30 June at 3pm and 1 July at 8.30pm