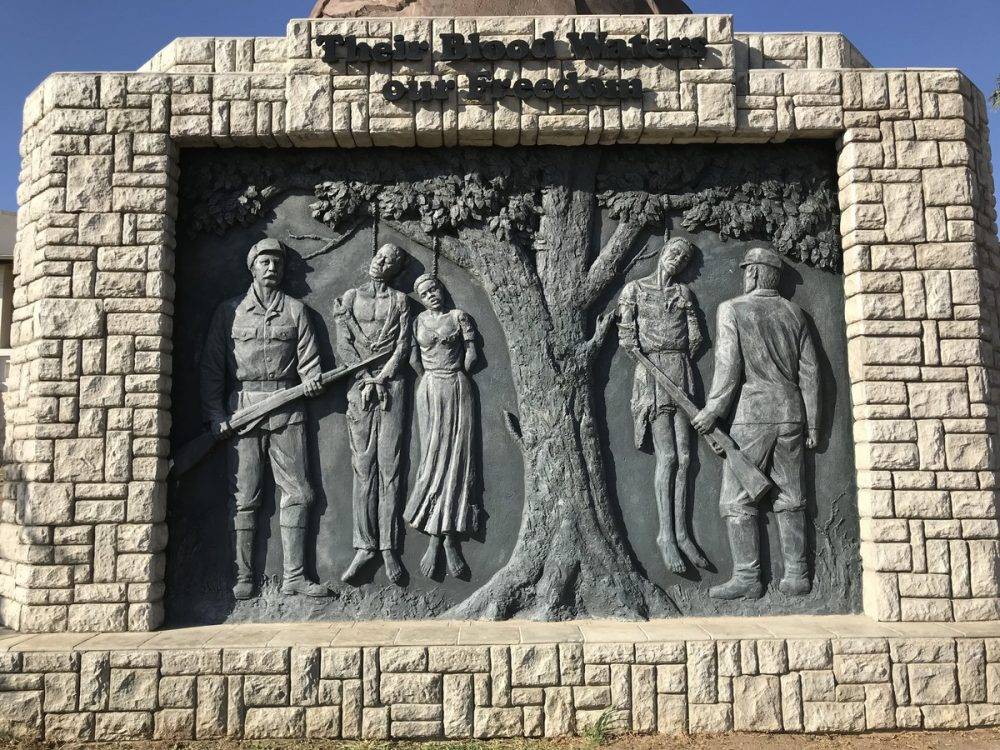

Blood and freedom: A memorial in the Namibian capital Windhoek to the genocide of the Herero and Nama committed by German colonial troops from 1904 to 1907. Photo: Jürgen Bätz/Getty Images

A colonial gaze — like the romantic conceptions of European life in African colonies popularised by the Hollywood movie Out of Africa — is reproduced in Germany in a whole range of narratives in which women describe their interactions with locals, even if they do not quite “go native”.

Among the most prominent and successful examples is Corinne Hofmann’s Die Weiße Massai (The White Masai). The book was such a bestseller that two more novels followed.

It was also turned into a movie, and the author summarised her passion for Africa in another monograph.

As scholar Dirk Göttsche observed in Remembering Africa: “One of the modern twists in the reenactment of colonial myths … is the shift from the male heroes of colonial novels to the female protagonists of recent works.

“These sometimes combine the fascination of colonial adventure in exotic terrain with the stance of a courageous anticolonialism in colonial space which gives rise to yet another myth, which is postcolonial only in the historical sense of the term, namely the myth of a ‘better colonialism’ (Sartre’s term) which history failed to give a chance to develop.”

Many of these narratives reinforce in the reader a sense of paternalistic faux open-mindedness that views the “other” through the lens of a dominant monocultural Germany.

This contrasts with the case of the renowned South African novelist André Brink (1935 – 2015): counteracting romanticising clichés, he described the brutality of colonial frontier society in The Other Side of Silence, a novel that evoked the particular horrors of war in German Southwest Africa, including the gendered violence of that conflict.

Many of Brink’s novels, located in mainly historical colonial settings of South Africa, were published in Germany by the large publishing house Kiepenheuer & Witsch.

The Other Side of Silence, however, was considered unsuitable for a German audience — which indeed might have been true for a public caught up in colonial amnesia or at least an unwillingness to face the brutal side of history. It required a rather small publisher to produce a German version.

While of late the combination of postcolonial and memory studies has provided a productive context for narrative literature as well, this should not lead us to hastily conclude that they have already decisively shifted public mainstream discourses. Nor has the genre avoided the danger of regressing into appropriations, re-mystifications and stereotyping.

An overview of recent African literature published in German could create the misleading impression that this genre is widely established and recognised. But African literature remains, with very few exceptions, a niche genre and is mainly published by committed smaller publishing houses.

While a few novels of the Tanzanian-British writer Abdulrazak Gurnah were translated and distributed by mainly smaller publishers in limited print runs between 1986 and 2006, these were all unavailable at the time he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in October 2021.

That Gurnah, despite his literary engagement with German colonial East Africa, was considered by the German media to be widely unknown can be dismissed as a bid to justify their own ignorance. His novel Afterlives had received prominent reviews as a masterpiece in the established international media.

A leading journalist in […] Die Welt quoted in a tweet the citation of the Nobel Prize Committee, which stated that Gurnah was selected “for his uncompromising and compassionate penetration of the effects of colonialism and the fate of the refugee in the gulf between cultures and continents”. The journalist then commented: “Well-behaved.”

The contrast between such an arrogant and limited view and the inclusive empathy of Gurnah could hardly be stronger. It illustrates the divide between the tunnel vision of white supremacy, a form of mental imprisonment, and universal humanism.

Years before, Gurnah had disclosed in an interview with the German newspaper Stuttgarter Zeitung that as a 15-year-old he cried when reading Anna Karenina, despite knowing nothing about 19th-century Russia. Tolstoy, he explained, writes about human emotions which can be understood by all.

• Melber is an associate at the Nordic Africa Institute in Uppsala, extraordinary professor at the department of political sciences at the University of Pretoria and at the Centre for Gender and Africa Studies at the University of the Free State. He is senior research fellow at the Institute of Commonwealth Studies of the University of London.

• The Long Shadow of German Colonialism is published by C Hurst & Co and distributed in South Africa by Blue Weaver.