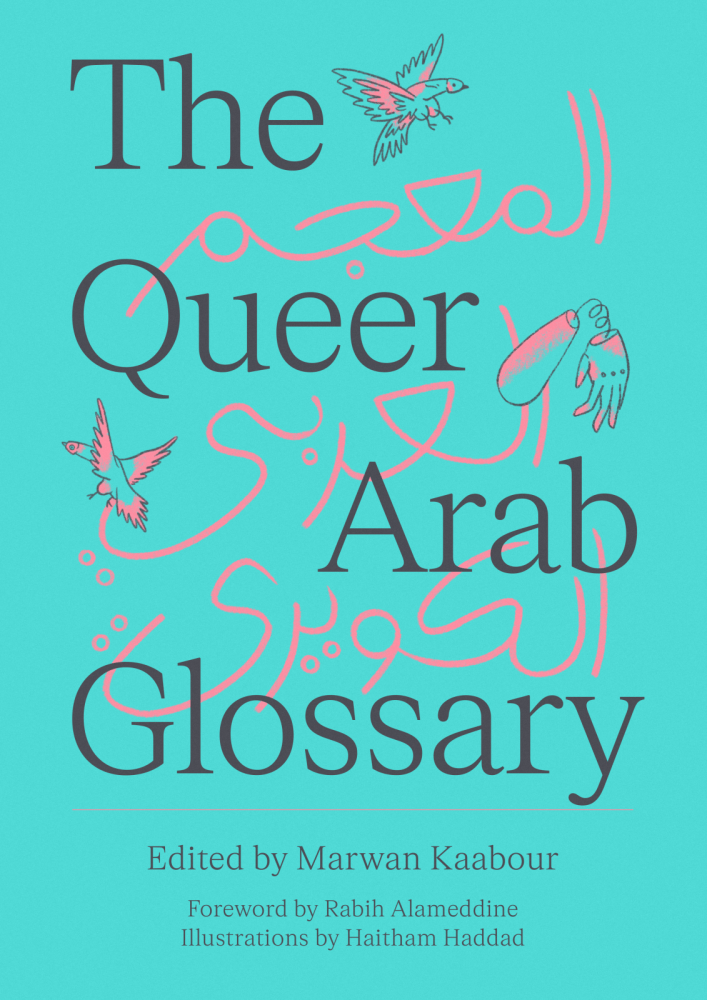

Tome: Marwan Kaabour is the author of The Queer Arab Glossary, which explains more than 300 Arabic slang words.

London-based Lebanese artist and graphic designer Marwan Kaabour refers to his book, The Queer Arab Glossary, as “a love letter” to his community. The “letter” is, however, more akin to a tome. Covering Sudanese, Egyptian, Levantine, Maghrebi, Iraqi and Gulf dialects, the book is impressive in scale, containing the definitions of more than 300 slang Arabic words used to describe queer people (some affectionate; most, derogatory).

The book, which took four years to complete, also includes essays and delightful illustrations that put a playful and queer-affirming spin on some of the often offensive terms.

In this interview with Carl Collison, Kaabour speaks about the reasons behind tackling this ambitious project, the patriarchy inherent in language and his inclusion of a section of the global queer community so often “ignored”.

Carl Collison (CC): I found it telling — and kind of amusing — when I opened the Sudanese dialect section of the book and the very first entry was “Awlad Mik” (“Mickey Mouse kids”), which alludes to the perception that queerness in Africa is as a result of “Western influence”. But then, you also have lots of entries which date back to pre-colonial days. There’s the beautiful essay, A Rich Constellation of Identities, by Saqer Almarri, where they write about a manuscript that dates back to the 1300s in which reference is made to what we would today call intersex people. And so there’s a kind of contradiction in how queerness is seen across the Arab world. What other contradictions or differences did you notice in your research?

Marwan Kaabour (MK): If I need to talk about the book, I also just need to talk about Takweer, which is the project that gave birth to the book. Takweer is this platform that I created in 2019, out of frustration with these things that you touched on: the idea that we hear in our own … Arab context that queerness is a Western import. And the Western perspective that us Arabs are people who are born homophobic and sexist and backward and barbarians and all of that. So Takweer … and the book operate in the same way: it’s simply us celebrating our own culture with queerness in mind. But it’s also to debunk these myths that queerness is a Western import — or that we are incapable of embracing queer people. But the book is a survey of the linguistic landscape around queerness. And by survey, I mean everything. So it’s not just the good words or the politically correct words, it’s all of the words.

So, of course, there [are] going to be many, many contradictions when you look at this entire range. But it is correct to mention that if queerness is indeed a Western import, then how come Arab communities …have been talking about it and documenting it [for] as long as these communities have existed? You touched on Saqer Almarri’s essay that specifically dissects the root of the word “khuntha” or “khanith”, which is the very old-school, historic Islamic term to refer to someone who is intersex or gender ambiguous or effeminate. The definitions really vary. So clearly, we’ve been there from the beginning. Obviously, queerness is not a Western import. The way we are dealing with it is what has changed over time.

CC: I also noticed … the vast difference in the number of terms referring to queer men and cisgendered queer women. And there are also so many more derogatory terms for the more effeminate, bottom-perceived queer man — and the terms for the [more masculine-presenting queer] men are kind of almost … not reverential, but more respectful. To me, it really highlighted the patriarchy in language …

MK: The queer community is like a miniature version of regular society, and the patriarchy and the misogyny that permeates general society makes its way into the queer community. Now, obviously, as you’ve rightly noted, most of the words in the book are derogatory, because we are still not at a point where we have developed such a vast vocabulary between members of the community to talk about our experience, which is what I hope my book tries to trigger. But how do you demean someone? How do you insult someone in this context? When it comes to queer men, you try to compare them to women, because that apparently demeans or belittles [them] or takes away from their masculinity.

Now, with queer women, there [are] two parts to it. The words that do exist always bring the queer women back to the man. As in, she’s … “mistarjila”, which means she is “like a man”. She is a “boya”, which is the feminisation of the word “boy” … So, it’s all to say that she is acting this way, because she is like a man, not because she is a woman …who has exercised her right to love and do whatever she wants with her body, and to express her sexuality.

The second part is how little of these words exist. And it’s the other facet of misogyny, which doesn’t even give value or seriousness to a woman’s sexuality. So, we’re not going to even acknowledge her choices, or her life. And when we do, we are going to say it’s like the man.

CC: Let’s talk about the African followers of Takweer. In their comments, do they talk about the need to have their identities written about or acknowledged? Is that something that you’ve noticed?

MK: Absolutely. Look, I mean … with Takweer and with the book, it’s been a massively educational journey for me because, you know, I need to acknowledge my positionality as a cis gay man from the Levant area of the Arab world. [Because] even though we sometimes look at the Arab world as this monolith, it’s made up of massively diverse and often contradictory communities, with contradictory definitions of what it means to be Arab … So, when I attempted to create a platform like Takweer to talk about the queer Arab identity, I must look at all of its facets and not just the ones that usually make it into the media, which are usually Middle Eastern and Egyptian.

So that has forced me to step out of my comfort zone and look beyond what I know, and engage with our queer siblings across the African continent as well. And … it’s the followers who bring to my attention stories that I need to tell … It’s the community and the followers themselves who … tell me, “Look, you should look at the singer who was, you know, gender non-conforming in turn of the century Morocco,” for example. And they broaden my understanding of what it means to be Arab.

CC: I love the inclusive nature of that approach. It’s kind of “queering” knowledge production.

MK: Oh, fully! I think I’m quite lucky that I don’t come from a research or academic background. I’m a graphic designer. That’s my background. And I think it liberates me from a lot of the shackles of academia and research.

And you should see, at a few book events I’ve had recently, specifically people from Sudan or from North Africa will come up to me so emotional that I included them in the book; that there’s a Sudanese section. Imagine I put out a book that claims to represent the entirety of the Arabic-speaking communities and just ignore a whole chunk of it. But it becomes so normalised to forget that part of the Arab world … that it seems like a surprise or a privilege to be included.

CC: What are some of the things that have stood out for you in terms of the comments by African followers of Takweer? What are they feeling?

MK: [There is] a thirst and a demand to be included. I think the discourse is usually quite dominated by specific parts of the Arab community. So what Arab African followers do is demand their space and demand … that they are included in the narrative. They want to be seen and not erased, yet again … I keep saying the book is the first realised project to come out of Takweer. Because what I’m planning on doing is to follow it up with projects … that continue to tell the story. There’s a wealth of knowledge that has been relegated to footnotes.

This is an edited version of an interview originally published by Beyond the Margins.