Journalist and writer Gavin Evans

When I meet Gavin Evans on a Friday morning, it’s to talk about his memoir Son of a Preacher Man, which he’s visiting South Africa to promote.

But I’m more interested in hearing what it was like to report for the Mail & Guardian in the dying days of apartheid. Evans was one of the first reporters hired by the paper.

It was the mid-Eighties, and Evans had just started his career in Gqeberha, then known as Port Elizabeth. “My journalism career started at the Eastern Province Herald in ’84,” he recalls.

“There was a company then called South African Associated Newspapers. They had a three-month programme and all the new journalists went through it. After that, you started at places like the Eastern Province Herald or the Post. I was on the Herald.”

Evans’ journey would soon take him to the Rand Daily Mail, Business Day and eventually the pioneering Weekly Mail, which would later become the Mail & Guardian.

“I knew Anton Harber because he’d also been at the Rand Daily Mail,” Evans explains.

“Irwin Manoim was there too, and Clive Cope was around. They were the three who set it up. I went along to the opening meeting and came up with story ideas. Initially, I was freelancing while working for the SAN Transvaal News Bureau. But then Anton offered me a job.”

For Evans, joining the Weekly Mail was more than just a career move, it was a leap into a newsroom that operated with a shared spirit of purpose.

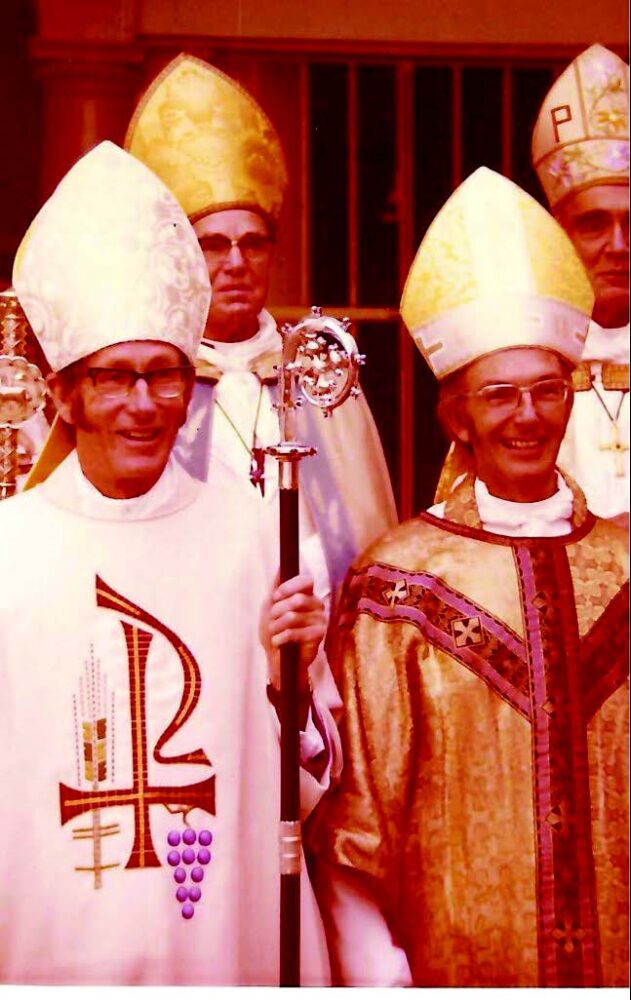

Gavin Evans’ father Bruce’s consecration in 1975

Gavin Evans’ father Bruce’s consecration in 1975

“It was a wonderful working environment,” he says. “Everyone got paid the same, from editors to everyone else. I don’t know about the cleaning staff, but for all the journalists, it was the same salary. It was a brave decision but it worked for a while.”

At the Weekly Mail, Evans carved out a distinctive voice.

“Initially, I was doing politics,” he says, “but I knew a lot about boxing. So, I said, ‘You guys need a boxing correspondent!’ I wrote about boxing in a different way. The other boxing correspondents were white guys who didn’t know any of the black boxers. I did. I had access nobody else had.”

His work soon drew the attention of the Sunday Times, which asked him to be their boxing correspondent too. Evans also became the mysterious voice behind the Weekly Mail’s satirical gossip column.

“No one was told except for a few people in the know who the writer behind it was,” he explains. “We were poking fun at government people, and writing it in a tone of naivety, but of course it was all about exposing them. John Perlman did it before me, and then I was the writer of the column for probably the longest stretch — at least two years.”

The era was dangerous for journalists willing to speak truth to power. Evans recalls the paper’s investigative spirit, which led to the exposure of the so-called “third force” — the apartheid state’s clandestine efforts to foment violence.

“We broke the story of the Civil Cooperation Bureau (CCB), the state’s assassination group,” he says.

“Military intelligence was funding Inkatha to hack people to death on the trains. We broke that story too.”

Evans’ investigations and his political activity with the ANC and SACP made him a target. In the late Eighties, he says, the CCB hired “Peaches” Gordon, a killer from a notorious Cape Town gang, to assassinate him.

“His instructions were to stab me to death and steal my watch and wallet to make it look like a straight robbery,” Evans says evenly.

“But I was in hiding at the time. The ANC had said to me, ‘You must go into hiding.’ I stayed in 18 different houses in six months — all in Johannesburg. I’d move and move and move. He followed me to five houses but each time I’d already left weeks before.”

Even the killer’s ruse of offering sensitive documents, something that had once yielded a groundbreaking story for Evans, couldn’t lure him out.

“He phoned me and said, ‘I’m a comrade. I’ve got documents for you about the state. Can you meet me?’ But there was something about him that didn’t ring true. So I didn’t turn up. It turned out to be my life he was after.”

By the end of the Eighties, the Weekly Mail, along with international partners, had exposed the third force’s operations. In the aftermath, the government scrambled to contain the fallout.

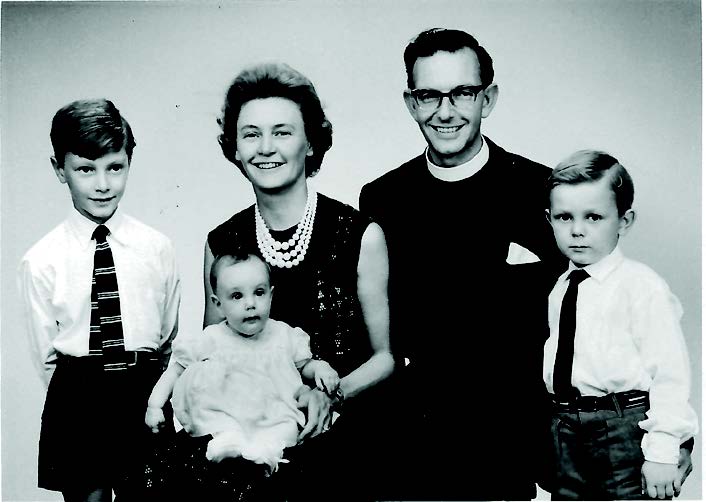

A family portrait of Joan, Bruce, Michael and Gavin from 1965

A family portrait of Joan, Bruce, Michael and Gavin from 1965

“They set up a tame judge, Justice Harms, and the Harms Commission to investigate,” Evans says.

“They admitted all the failed assassinations, including mine. Peaches Gordon was arrested and gave a full statement, including in my case. Then they released him, but he was later killed by the CCB with a bullet to the back of his head.”

Evans had a complicated relationship with his father, who was a man of peace, but also of contradictions. In Son of a Preacher Man, he grapples with these paradoxes — his father’s fervent faith and quiet complicity, his support for his son’s political defiance and his own hand in shaping a world where violence was a constant threat.

“I never even looked at my earlier book when I wrote this one,” Evans tells me. “I wanted it to be fresh.”

Son of a Preacher Man delves far deeper than his memoir, Dancing Shoes is Dead, which mingled his love for boxing with glimpses of his life.

Here, the focus is squarely on the fracture between father and son, a rift that began one night when Evans was 14 and his father beat him with his fists — a rift that only healed decades later, after an exchange of letters.

Listening to Evans recount his early years as a journalist in South Africa, it’s clear that the violence of the state — detentions, beatings, tyre-slashings — took a toll on him.

“I thought none of this affected me,” he says. “But it did. I was having dreams of being buried alive or escaping. I became more aggressive.”

These traumas burrowed deep into his psyche, manifesting in ways he didn’t recognise until much later.

Yet even in the darkness, there were moments of almost cinematic defiance. Evans recalls the day security police barged into his house, threatening him over military service.

“They said, ‘Either you cooperate, or the military police will arrest you at work.’ I told them, ‘Get the fuck out of my house!’”

The next day, his motorbike’s tyres were slashed. But in a surprising twist, his father quietly intervened.

Using his weight as a bishop, he wrote to the authorities, arguing that his son deserved a delay in conscription. Evans only discovered this act of paternal protection after his father’s death, when he stumbled upon the letters in a box of papers.

“It made me cry,” he says softly. “We’d always had a bit of distance, but I never told him I was proud of him too.”

That fragile reconciliation came just before his father’s final decline. Diagnosed with motor neurone disease, he had less than a year to live. Evans speaks of those last months with a tenderness that cuts through the decades of conflict: “We had our reckoning, and then it was gone.”

If there’s a thread running through Evans’ life, it’s the question of what it means to stand firm when the world seems determined to push you down. In South Africa, that meant working for the M&G during its tumultuous early years — reporting from a newsroom in Braamfontein, trading stories and dodging censorship, feeling invincible in his twenties, even as he was detained and assaulted by the state.

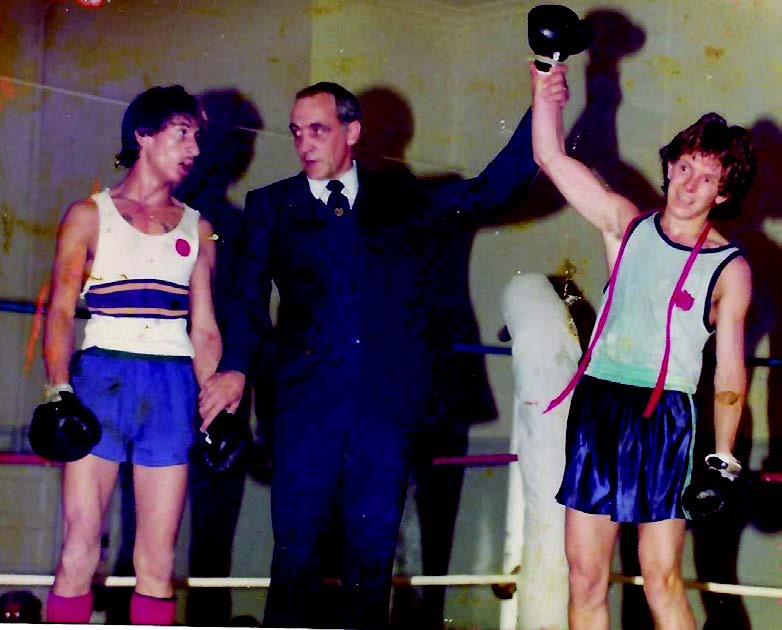

Gavin Evans’ last amateur fight in 1982 — a knock-out win.

Gavin Evans’ last amateur fight in 1982 — a knock-out win.

“You think it’s not affecting you,” he says. “But it does. It seeps in.”

After moving to England in the early Nineties, Evans continued to write and teach. Son of a Preacher Man is his ninth non-fiction book, and today he lectures first-year and postgraduate journalism students at Birkbeck, University of London.

Evans, now 65, speaks of his family.

“I’ve got two daughters, Tessa and Caitlyn, both of whom appear in the book. Towards the end, there’s a chapter about Tessa and her husband Ciaran and their son, Ferdi.

“The final chapter is all about Ferdi. You know, the book’s about fathers and sons, and now it’s also about grandfathers and grandsons, because I spend a lot of time with Ferdi. I adore him. He’s three and three-quarters, and if you ask him how old he is, that’s what he’ll tell you — three and three-quarters.”

These personal milestones deepened his understanding of the legacy of fatherhood, both in the book and in life. Reflecting on his days as a young journalist in South Africa and his complex relationship with his father, Evans sees his own journey as a testament to resilience and the redemptive power of storytelling.

As he guides the next generation of journalists, he remains mindful of the lessons of the past and the bright promise of those still to come.