Calvin Ratladi sees beyond the script, conjuring ghosts of land, legacy and loss in ‘Breakfast with Mugabe’

The first thing I noticed about Calvin Ratladi were his eyes. Huge, mysterious pools of something warm and comforting. We met on the stairs leading up to Rhodes Theatre in Makhanda where the play he directed for this year’s National Arts Festival was about to premiere.

Instead of the jingle-jangle of pre-show nervousness, what I saw in his wise and gentle eyes was calm, unabashed patience — an artist’s quiet expectation minutes before the public sees a work for the first time.

And below the eyes, an openhearted smile, the kind you cherish long after you meet him.

For those few moments — “hello”, “great to meet you”, “break a leg” — Ratladi, who is this year’s Standard Bank Young Artist for Theatre, looked at me with such intensity it was as if we were old friends.

His eyes were, I thought, those of someone with a talent for baring his soul, someone familiar with the sensation of opening himself up in front of an audience. It was weird then to later hear him tell me that he avoids looking at people for too long.

“Usually, I don’t look at people when I speak to them,” he told me during a lunchtime interview a few days later. “I hardly look at people at all, because when I do, I start seeing beyond …”

And although his words trailed off then, I understood what he meant, knew that what he was alluding to was a gift, a sensitivity that has doubtlessly fuelled his artistic vision. “I’ve always known about this,” he says.

His ability to see below the surface, see “beyond” what exists in the physical realm, is precisely what catches you off guard in his new play, Breakfast with Mugabe, which — after its debut run in Makhanda — opens this week at the Market Theatre in Johannesburg.

It’s a curious and demanding play, one that works hard for the audience’s attention, and requires intense listening. If you do fall under its spell, you’re rewarded with insights you don’t see coming. It also appeals to what Ratladi refers to as “an African palate” — something that might just throw you off guard with its alternative imagining of an otherwise well-documented sliver of history.

“In my storytelling, it’s never just entertainment,” he says. “There’s also advocacy, and there’s a conversation.”

And, yes, there’s a potential provocation.

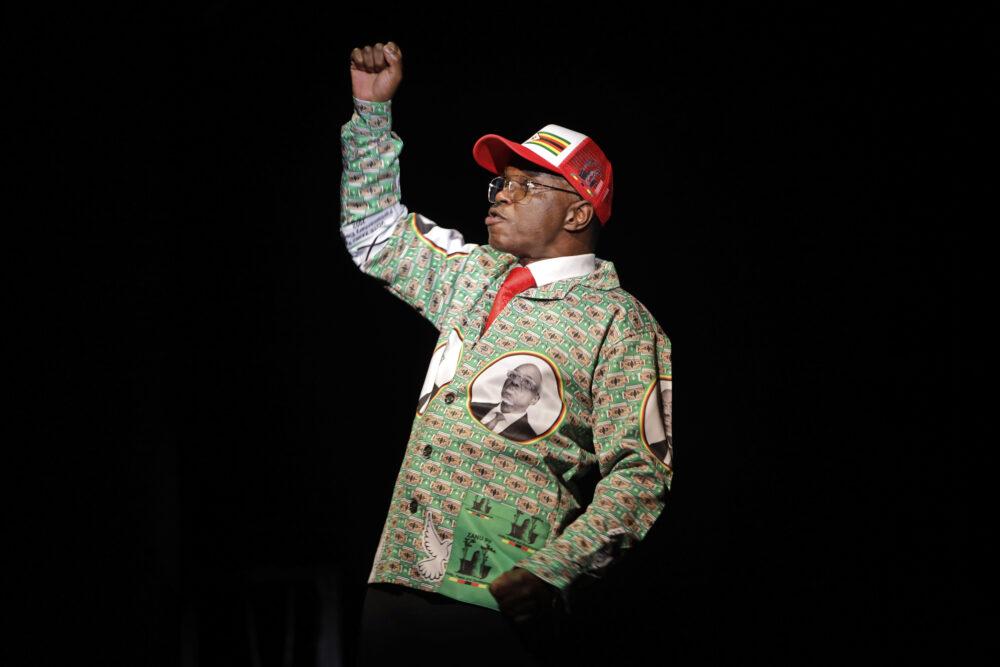

Themba Ndaba plays Robert Mugabe in Breakfast with Mugabe, directed by Calvin Ratladi. (Mark Wessels)

Themba Ndaba plays Robert Mugabe in Breakfast with Mugabe, directed by Calvin Ratladi. (Mark Wessels)

In his work, he wants to take you somewhere you haven’t been before, and it’s not necessarily a comfortable place. When he created a performance about his father, a miner in his childhood home of Witbank, he says he imagined what it must be like to spend so much of one’s life far beneath the surface of the earth. And that was the emotional journey he shared with his audience.

In Breakfast with Mugabe, he uses a classically-shaped play to take the audience through the veil, to share insight into a realm of spiritual reckoning beyond the rational, and to drive home the dichotomy of two worlds co-existing.

The play, written in 2005 by the Cambridge-based writer Fraser Grace, feels particularly poignant at a time when populist authoritarians are having a global moment. It is not a play about Mugabe’s rise to power, though, but of a period during his rule when he is plagued by some manifestation, haunted by unresolved grief. And the play hints that what’s generally ascribed to paranoia might be something quite different, something unknowable if viewed through a Eurocentric lens.

The play has weighed on Ratladi since he first read it in 2016. He tried to produce it previously but couldn’t raise the funding; he says it’s not the kind of show that can be staged on the cheap.

There have been passing thoughts, too, such as casting himself as Mugabe, with non-binary performance artist Albert Ibokwe Khoza in the role of Grace Mugabe. “I wondered what it would have meant if I played Robert Mugabe with my body, to go against expectations, push boundaries.”

His reference to “my body” is an allusion to his small stature, an effect of kyphoscoliosis, an abnormal curvature of the spine which is chronic and incurable. Despite its effect on his physical health and on his ability to do some things most of us take for granted (like drive a car), the condition has not stood in the way of his focus on advocating — through storytelling — for a better world.

Nonetheless, while his theatre work has earned him acclaim and has been even more widely embraced overseas, he’s perhaps best known for his role as Goloza in Shaka iLembe, the popular television series that last month entered its second season on Mzansi Magic.

While Ratladi has wanted to be a director since his early-20s, he says he has spent his career accidentally being cast in performing parts, a number of them created specifically for him — despite trying to avoid performing. He says just about everything he’s ever acted in, including Shaka iLembe, “came from coincidences”.

Breakfast with Mugabe was no coincidence, though. “I love classics … Macbeth, King Lear, Miss Julie … I love them. And this seemed like a classical play to me, a big story with great depth.”

Breakfast with Mugabe also grapples with ideas and themes that recur in works Ratladi has created. (Mark Wessels)

Breakfast with Mugabe also grapples with ideas and themes that recur in works Ratladi has created. (Mark Wessels)

It also grapples with ideas and themes that recur in works he’s created. “What seems to come up over and over in my work are issues of land, of memory, and of power. I found these issues paralleled in the play.”

In the end, he cast Themba Ndaba as Mugabe and Gontse Ntshegang as Grace, with Craig Jackson as Dr Peric, the psychiatrist summoned to attend to the Zimbabwean president’s mounting psychological torment. Ratladi says the play requires actors with stamina who can carry the weight of the drama, endure the heaviness, not to mention the many words.

What you notice first about the play is the set, which suggests an almost violent collision between two worlds: a presidential living room imbued with all the trappings of modern Western existence and, surrounding it, a disconcerting African wasteland of dirt and rubble and shattered earth. It is as though some colonial edifice has been torn out of the earth.

Discussing the design, Ratladi spoke of the fact that, growing up in a mining environment, this shattered landscape was his reality. “It’s what I grew up surrounded by — the mining industry. I grew up in the mines. So it’s about the landscape I grew up with. That’s what the set is.”

The issue of the land — and the destructiveness of mining — is, of course, a key issue in any sort of post-colonial analysis of African history. And there’s something elegiac about this part of the set. It’s barely used, though, until — during a truly creepy and ethereal moment in the play — it dawns on you that it is a kind of spiritual wasteland. It’s a realisation that shifts the play’s entire axis of meaning.

For Ratladi, the set’s design visually and figuratively sets up the dichotomy that’s at the heart of the play.

“There’s the European side and there’s the spiritual side in Africa.”

In his sketches of the set, he says he referred to it as “a split personality”, which is something “a lot of Africans have”. He says the set represents these dichotomies, such as the capacity to simultaneously embrace African spirituality and Christianity.

Ratladi says he was fascinated with the idea that “what was being regarded as paranoia, a psychological issue in the play, for me was a spiritual issue — that’s what I saw this figure of Mugabe actually grappling with as a person”.

“I think some audiences will come with a racial eye,” Ratladi says. “It’s hard not to, because there are so many triggers. Some will feel cheated, some will feel otherwise. For me, that’s the conversation I’m trying to have with people. To discuss the fact that as much as Mugabe was so passionate about the land and taking it back, he’s the same man who earned seven degrees while in prison, and who had embraced Western ways of thinking. He sought medical help in Europe rather than from the people around him.”

Ratladi is interested in the paradoxes and in the possibilities those paradoxes open up. Which is why, when he looks into the story, it seems to him that “there was a spiritual awakening that wasn’t fully embraced — and it caused a lot of suffering”.

“I was interested in what’s not in the media, and also not in the script. I was interested in where we might be missing parts of the story of this man about whom so much has been said and written.”

He says that, as much as the work might have a political message, there is always a human element, always a personal story at the heart of the wider picture. A nation might be suffering, but what if the cause is a personal pain or affliction being experienced by the nation’s leader? It’s that dichotomy — between the public and personal story — that he’s also interested in with this play.

Ratladi says that is the power of theatre; to convey big ideas through a very personal, intimate and digestible story. You sit there in the dark for an hour or two and are not lectured to, but get to witness — and feel — another worldview.

Breakfast with Mugabe plays at the Market Theatre from 16 July until 10 August.