Emotional depth: Composer Zethu Mashika is exactly where he wants to be – painting a picture with his music for films that strengthen the frames and dialogue

It’s a Friday night in August 2009 when Zethu Mashika makes a call that changes everything. It’s his birthday month and he’s about to be given an opportunity that will alter the path of his life. A spontaneous check-in with a friend turns into an invitation: “Don’t you want to make music for a film?”

This is the night that Mashika discovered film scoring. He had happened to find his friend in the middle of an emergency, struggling to make the music for a grad film he was working on.

“They came to pick me up and I scored [the film],” he says. “That’s when I caught the bug, got infected, and then, you know, the rest is history.”

Mashika, born and raised in Benoni, Gauteng, had been working as an artist and producer, a career that began in 2003 during the surge of South African hip-hop and kwaito.

“I was the artist, producer type. I got to produce some tracks on Flabba’s album. At that time the Zulu Mob and H2O were the big guys. And then I did a track with RJ Benjamin.”

During his years as a producer, he explored different genres of music, including rock and Chinese, to figure out which lane he would thrive in.

Among his experiments was film music, which didn’t make much sense to him at first.

“When I listen back, it sounds horrible.”

But something in it stuck.

“I didn’t realise it would build the life I wanted, or make me the person I wanted to be. You’re not sure until you actually do it.”

After that first short film, everything changed.

“It was 12 minutes long, and I scored the whole thing in one night. I wouldn’t do that today,” he laughs. “But when I came back, I was no longer a producer. I was a composer.”

After discovering his passion for film composition, Mashika shifted his focus from producing music to creating scores that enhance visual storytelling.

Mashika rebranded himself overnight. He started downloading trailers, stripping them of sound and scoring them for practice. He then used those as pitch material. “That’s how I got my first film.”

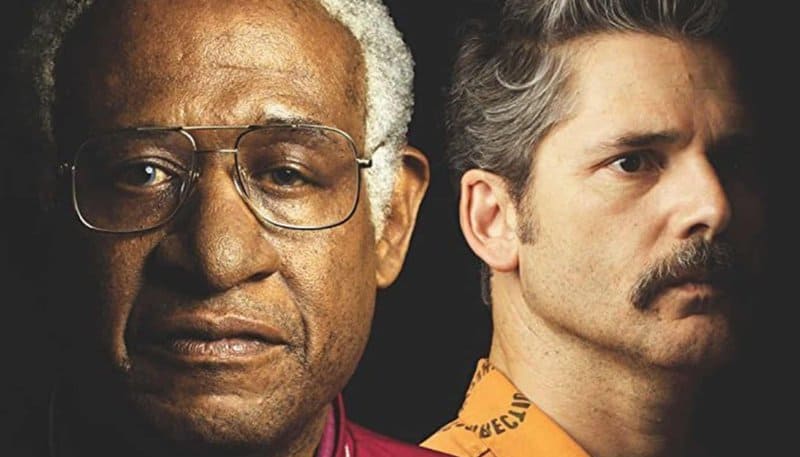

Meaning: The score for Go (left) is Zethu Mashika’s son’s going-to-school music. He worked with Forest Whitaker and Eric Bana (right) on The Forgiven. Photos: Netflix & Light and Dark Films

Meaning: The score for Go (left) is Zethu Mashika’s son’s going-to-school music. He worked with Forest Whitaker and Eric Bana (right) on The Forgiven. Photos: Netflix & Light and Dark Films

The experience of scoring the grad film ignited a newfound dedication within him, one that would lead to him having a successful career in the industry as a film composer.

He landed his first professional project, Zama Zama. Before he could even start working on it, another opportunity landed: SKYF, starring Thapelo Mokoena. Although Zama Zama came first, SKYF was his first fully completed feature. A South African Film and Television Awards nomination followed soon after for his work on Zama Zama.

“It was a stamp. Like, ‘Yes. This is it,’” he said.

While he didn’t win that award, he went on to win a SAFTA in 2024 for his work on Classified, a series currently streaming on Netflix and Amazon Prime Video.

The projects kept rolling. One of Mashika’s most significant was the 2017 feature The Forgiven, starring Forest Whitaker and Eric Bana.

“That was a big one. A proper learning curve. You see how the machine moves on that level: how an editor works, how a director with depth directs.”

Working with directors who bring vision and emotional depth reshaped how Mashika thought about music in film.

“There’s a difference between curating pretty shots and telling a story. Same with music. Some just do background music. Others push you to go deeper. When you work with someone like that, you’re not just making sounds, you’re putting in layers.”

He likens it to becoming an “active watcher” involved in every frame and every line of dialogue. “That changes how you compose.”

The creative process for a score looks different for every composer. Mashika’s requires a helping hand from digital tools.

“Every time I start a film, I’m like: I don’t know if I can do this. Only 12 notes! You have to find a combination no one’s done that still fits the picture, the psychology, the world.”

Unlike many composers, Mashika doesn’t play instruments. “No muscle memory. I hear everything in my head, and I input the notes with a mouse, one by one.”

That limitation is a strength. “It’s slow, but it’s intimate. I know why every note is there, why every gap matters. Some just go with ‘sounds good’. But I know why I’m putting icy strings down low, or that brass over there. It’s painting a picture.”

He’s also keeping up with new tech, tools that let him hum melodies into a mic, which then generate MIDI data. “It’s weird. But it’s fun.”

Mashika’s sound is distinct: a mix of brass, strings, alternative synths and voice. Each has its emotional use. “Brass can fill a space like nothing else. It’s triumphant, but you can make it sound so sad. Strings can go dark. Synths, especially the weird ones, blur the line between music and sound design.”

His inspirations include giants such as Hans Zimmer, Jóhann Jóhannsson and Ludwig Göransson, but Mashika’s approach is personal. He describes himself as a spiritual composer, for whom work and life are one and the same.

“There are people who have a job and then a life. For me, they’re the same. I shoot my wife’s commercials for fun. I help with her photo shoots. I like being on set. It’s all the same energy.”

That energy has spilled into fatherhood. On car rides to school, his four-year-old son, Zulu, insists on listening to tracks from Go, a recent Netflix project Mashika scored. “That’s now our school music. He sings along. It’s the best thing.”

At this point in his life, Mashika says there’s nowhere else he’d rather be.

“When you see how your music affects a film, how empty it is without it, you know you’re exactly where you need to be.”