PRETTY FLY FOR A WHITE GUY: Francois Venter is a big rock climber who once drank tequila with the virologist rockstar Dexter Holland of The Offspring. He’s also one of the country’s leading HIV researchers. (Delywn Verasamy)

An inaugural lecture is a formal event thrown by a university to commemorate the lecturer’s appointment to full professorship. They are usually gravid, pinnacle-of-career moments.

Francois Venter’s inaugural lecture, held at the University of the Witwatersrand in 2023, was not typical. He began by describing how, for years, he had successfully dodged requests to deliver the lecture by blaming the university’s email system.

He confessed he missed a trick during the Covid-19 pandemic, “when I could have done this online”, and while he dutifully name-checked his professional role models and heroes, he also gave shout-outs to his tennis and rock climbing coaches, in between anecdotes about drinking tequila with Dexter Holland of The Offspring rock band (who earned his PhD in molecular biology in 2017) and being called by Standard Bank, twice (“I swear I turned this off …”).

Venter’s allergy to formalism, and to being in the spotlight, remains untreated.

ROCKING: Venter’s rock climbing adventures have taken him from Table Mountain to Vietnam, the US and onto this mountain near Vancouver, Canada. (Supplied)

ROCKING: Venter’s rock climbing adventures have taken him from Table Mountain to Vietnam, the US and onto this mountain near Vancouver, Canada. (Supplied)

“I hate, hate, hate talking about myself,” he warns.

We are sitting in the immaculate boardroom of Ezintsha, the Wits-based medical research centre that Venter leads. Ezintsha came to international attention in 2019 after the results of a clinical trial called ADVANCE were published in the New England Journal of Medicine, showing the effectiveness of new HIV therapies and, perhaps more importantly, demonstrating why it is important that clinical trials be conducted in the contexts in which the drugs are mainly consumed. The therapies worked but, as Venter puts it, “with complications peculiar to local populations, far from the sanitised world of curated pharmaceutical studies done on healthy white men”.

Venter, by this time, was already well known for his work in HIV, not only for his scientific outputs but for taking up cudgels on behalf of people living with HIV. In a series of recent op-eds, for example, Venter has excoriated both the president and the health minister for providing scant leadership in the face of the US’s defunding of the HIV response in South Africa, comparing their inaction to the infamous Aids denialism of former president Thabo Mbeki and his health minister Manto Tshabalala-Msimang.

Venter’s response to being singled out is predictable: “There are so many people in the HIV world who did much more and more bravely.” It is the refrain of many treatment activists and no deterrent to my questions about his childhood in the lowveld town of Phalaborwa.

The picture builds in fragments.

PHALABORWA IN MONOCHROME: Venter, second row, third from left, with classmates at Hoërskool Frans du Toit. (Supplied)

PHALABORWA IN MONOCHROME: Venter, second row, third from left, with classmates at Hoërskool Frans du Toit. (Supplied)

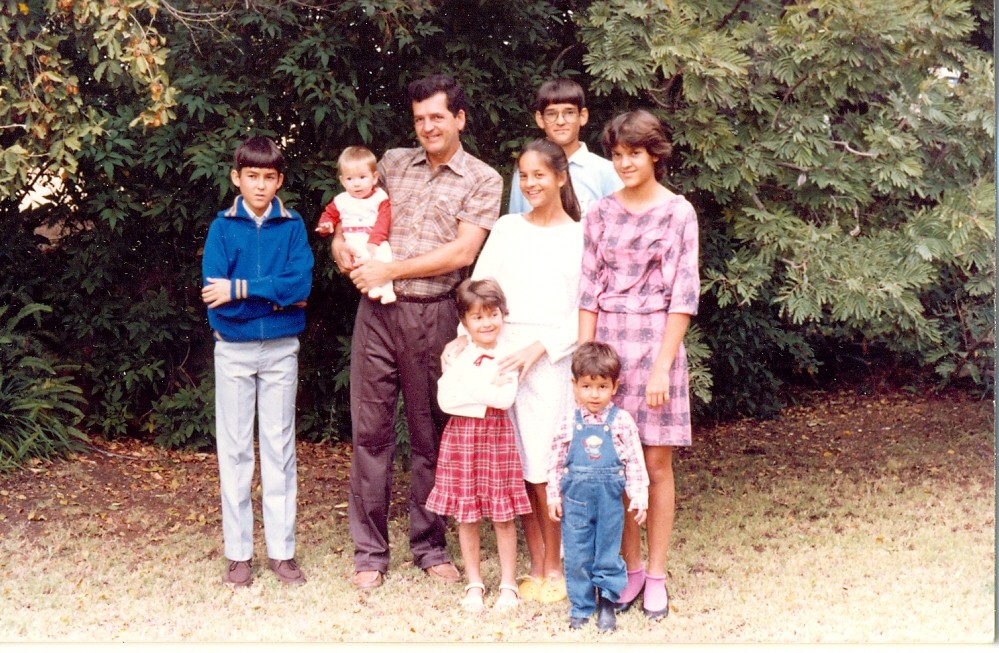

“The town has a paint colour named after it — Phalaborwa Dust — a sort of dull grey, which says everything, really,” says Venter, who was born in 1969, the first of seven children. Venter’s Afrikaans-speaking father worked as an accountant for the Palabora Mining Company, while his English mother ran a creche.

“You couldn’t have a family that size today,” he says.

“They managed because the company subsidised everything from education to golf club memberships.”

In a time of grand apartheid, Venter’s world was particularly white and insular. “Growing up, I never met a black person who wasn’t a servant,” he admits.

On Fridays, he and his fellow students were made to march in quasi-military uniforms. Sadistic corporal punishment and other forms of bullying had become “entrenched to an unthinking level”.

PHALABORWA IN COLOUR: Venter, in the back row, was born in 1969. The first of seven children, his father was an accountant for the Palabora Mining Company and his mother ran a local creche. (Supplied)

PHALABORWA IN COLOUR: Venter, in the back row, was born in 1969. The first of seven children, his father was an accountant for the Palabora Mining Company and his mother ran a local creche. (Supplied)

“I worked like crazy at school, knowing that was my ticket out of there,” says Venter, who worried his lowveld credentials would make him the odd man out at Wits medical school.

“Instead, I walked into this amazing diversity of people. For a boy who grew up on Springbok Radio, it was more than I had dreamed of,” he says, although admittedly the scene was intense and traumatising.

“All the hospitals were segregated, our training was segregated, even blood was segregated — white patients would only be given blood from black donors in extreme cases. It was just insane,” he says.

Cancel language

Venter is tall, powerfully built. The sharp edges of a forearm tattoo peek out of the sleeve of a black puffer jacket. His disposition is nervous, though, his speech often self-effacing, although mention one of his many bugbears and a quiet fury brims. Venter is known for speaking without any regard to self-preservation, using what a lecturer friend calls “borderline cancel language”. Like a good journalist, he calls it as he sees it.

ASK ME ABOUT MY CAT: Venter named one of his cats Fauci (right) after former US health czar Anthony Fauci, who helped steer the Covid-19 pandemic in the US. (Supplied)

ASK ME ABOUT MY CAT: Venter named one of his cats Fauci (right) after former US health czar Anthony Fauci, who helped steer the Covid-19 pandemic in the US. (Supplied)

The comparison pleases Venter, who was editor of the campus newspaper Wits Student in 1991. The publication had been overtly political since depicting Prime Minister John Vorster in a butcher’s outfit in 1973, and by the late 80s was the biggest of all the student papers in the country, having lost none of its satirical venom.

“I enjoyed the cut and thrust of the media and understanding its place in political life,” says Venter, who credits journalism with making him a better HIV researcher and political organiser (“I was able to chair meetings and construct agendas. It helped me to write grants and manuscripts.”)

He describes his involvement in student politics as an almost involuntary act, akin to staying afloat in a turbulent river.

“The late 80s were some of the worst for apartheid repression. Fellow students were being detained and tortured, their families maimed and disappeared. There were these extreme ideologies on campus — the United Democratic Front was very active — but at the same time there were people in my class saying the activists had it coming. That dissonance was difficult, but as far as I was concerned, there was nowhere for a white person to hide, and joining the fight [against apartheid] was the only moral choice.”

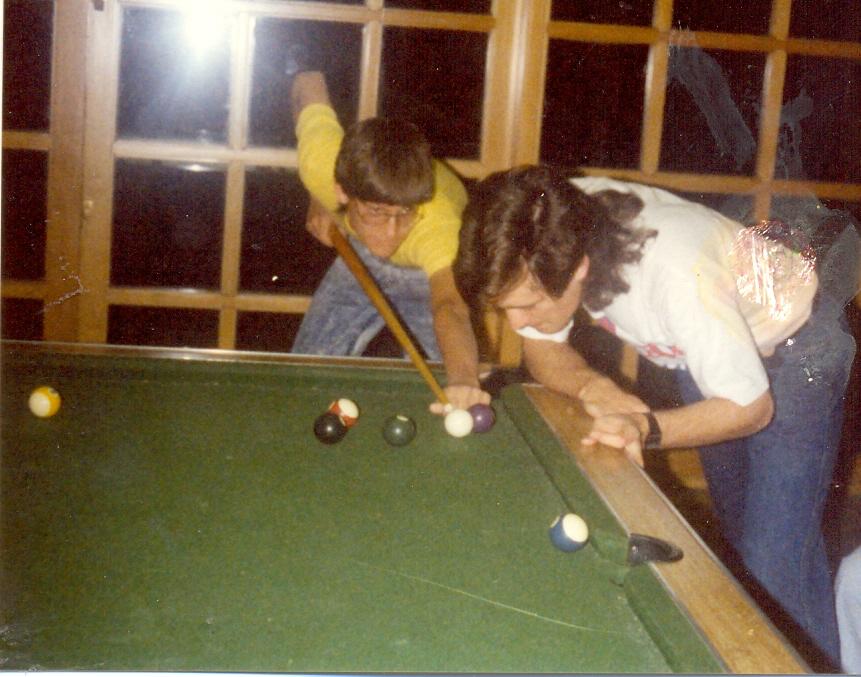

AT THE POOL: Venter, left, playing pool in res at Wits University with Damian Clarke, now a well-known trauma surgeon at UKZN. (Supplied)

AT THE POOL: Venter, left, playing pool in res at Wits University with Damian Clarke, now a well-known trauma surgeon at UKZN. (Supplied)

Medicine, in those first years, was at the edge of Venter’s concerns. He maintains he was a “mediocre student, at odds with many of my classmates”, although he pulled his socks up in his fifth year.

“I found I was enjoying clinical medicine and realised I needed to really knuckle down in order to stay in it.”

Dying in Baragwanath

Healthcare provided Venter with a clear view of the twistedness of apartheid policy.

“You go into the black hospitals and it’s like, jeez, the things that are happening there. Meanwhile, white people are receiving world-class care,” says Venter, who did his “house job” (residency) at Hillbrow Hospital, which is where he first encountered HIV as a student.

“It was the beginning of that incredible surge in numbers that occurred between 1993 and 1997. The first cases I saw were returning political exiles,” says Venter, who experienced an internal snap after an incident in a Yeoville restaurant.

“It was 1995, and I was nearing the end of a year at Helen Joseph Hospital. In those days Rocky Street was still quite eclectic and happening and I was hanging out in a restaurant run by this Caribbean guy I knew. He had booted out a young drug addict, who went across the street and bought a knife, came back and stabbed him in the heart.

“It was 10am. I tried to resuscitate him, but I had nothing. The waiters continued to serve the customers and stuff, stepping over his body. It was just such a savage thing. He bled to death in front of me, and I was like, fuck South Africa and its trauma and violence.”

Venter boarded a plane for the UK and a hospital job he found “terminally boring”. By 1997, he was back in Johannesburg, specialising in internal medicine. The HIV epidemic was at its zenith and hospitals across the country were overwhelmed.

“In some of the hospitals, like Bara [Baragwanath Hospital], you just left patients in casualty, and they would die there and go out the door. In Joburg Gen [Johannesburg General Hospital, today Charlotte Maxeke Johannesburg Academic Hospital] you put them on the floor in the corridors, and they died there waiting for a bed. It was brutal,” says Venter, who cautions against apportioning blame for this wave of death.

“The numbers had surged with a suddenness and severity that we still don’t really understand. Nelson Mandela was trying to prevent a race war. There really wasn’t much that he, or anybody else, could have done. I didn’t understand the transmission enough and we didn’t have the tools to prevent it.”

What Venter struggles to forgive, however, is the callousness of some senior administrators.

“As a junior doctor working in a Gauteng hospital I remember phoning the heads of health in the province and saying, ‘We’re full, can you redirect the ambulances?’ As far as I could see there were people lying on the floor, largely dying of Aids, but also with strokes, heart attacks. They were dying of pneumonia and TB.

“‘Who is from other provinces?’ the administrator asked me. ‘Send them back.’ And I was like, ‘Well, the problem, sir, is I’ve taken the history from this person from Mpumalanga, who has been sent from hospital to hospital and clinic to clinic, and they didn’t get help, you know, and that’s why they’re here.’ And he said, ‘I don’t care, send them back, they’re not supposed to be in Gauteng.’

“And looking back, that was the first sign of the absolute arrogance of some of the health people in government. And you see it now in the way foreigners and poor people are treated in the public sector. It is one thing to have no idea how to deal with a problem, but to lack the ability to do any reflection, have any empathy, and to self-correct is so upsetting.”

Toxic — and incredibly effective

On completion of his specialist time, Venter was burned out, and unsure of what to do with his life. He was interested in HIV, sparked by his experience of looking after a haemophiliac in 1997.

“The patient was one of a group that had HIV after receiving infected blood imported from the US by the state in the 1980s. The apartheid government took a decision to pay for their treatment with what was then extremely expensive antiretroviral therapy (ART), and the ANC government continued this,” says Venter, who was amazed at the impact of the drugs on his patient.

“I saw this patient in ICU just come off a ventilator, which just did not happen in those days.”

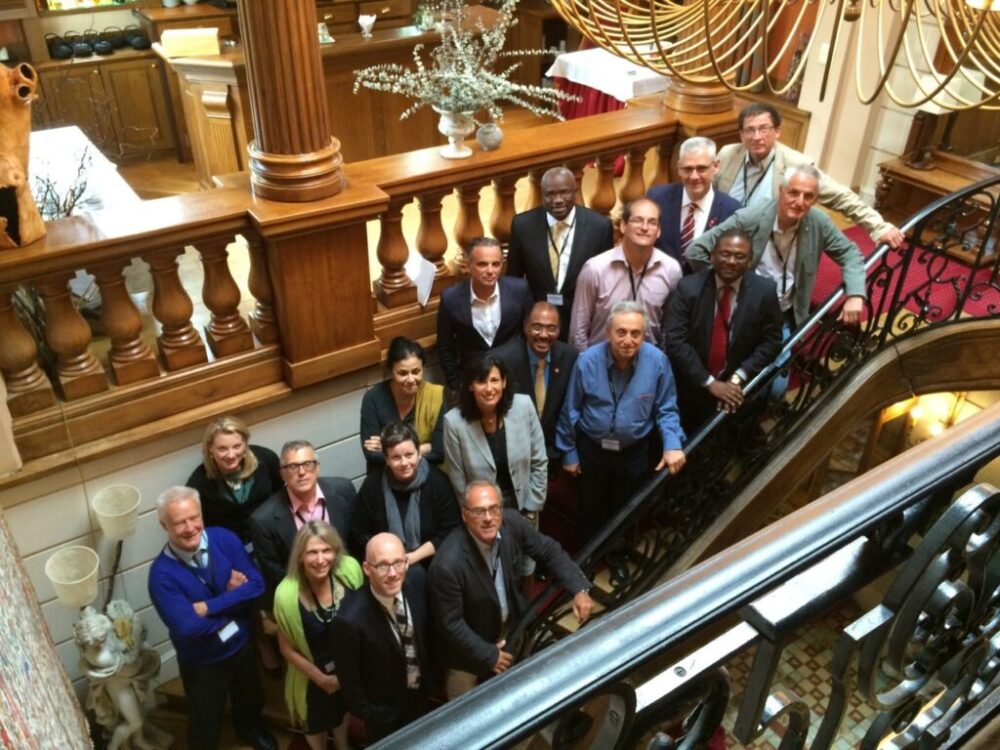

STEPPING UP: Francois Venter, third row from top, centre, at a 2014 HIV conference in Geneva, Switzerland, with some of the top international HIV/Aids experts. (Supplied)

STEPPING UP: Francois Venter, third row from top, centre, at a 2014 HIV conference in Geneva, Switzerland, with some of the top international HIV/Aids experts. (Supplied)

Venter was offered a job with the Wits-based Clinical HIV Research Unit by world-renowned HIV expert Ian Sanne, who, says Venter, “taught me how to do clinical trials, how to play with these toxic, incredibly effective drugs, and it was really the first time I was able to start seeing myself as someone who was going to get involved in HIV. The drugs have evolved since then, now more effective with almost no side effects.”

“We were working from a hopelessly overcrowded outpatient clinic in the then Johannesburg [now Charlotte Maxeke Johannesburg] Academic Hospital in which gay doctors had looked after gay men until the epidemic became more prevalent and they all left. I was working under this amazing endocrinologist called Jeffrey Wing and a dedicated Jewish GP called Clive Evian. At the time, it probably was the biggest HIV clinic on the continent, with queues out the door every day. That’s where I learned about HIV outpatient medicine,” says Venter.

It was also where Venter started interacting with the NGOs and activists then taking the fight for affordable ARTs to the government.

“We needed each other,” says Venter. “We needed access to the drugs and the Treatment Action Campaign had started smuggling them into the country. They needed proof that the drugs were effective in this context, and to treat their members and as many people as possible, and we had just started publishing findings from our cohort.

“It was devastating, though, watching them fighting our government to even acknowledge HIV existed, while their members died needing those drugs. The hypocrisy of senior political figures, many of whom had family members on antiretrovirals I was treating, yet didn’t call out Mbeki, is unforgivable.”

TEST SITE: In 2014, actor Matt Damon visits Esselen Street Clinic, an old Hillbrow facility, home to the first South African HIV testing site where Venter, left, ran a US-funded HIV support programme. (Supplied)

TEST SITE: In 2014, actor Matt Damon visits Esselen Street Clinic, an old Hillbrow facility, home to the first South African HIV testing site where Venter, left, ran a US-funded HIV support programme. (Supplied)

He then joined Professor Helen Rees’s Wits Reproductive Health and HIV Initiative and began working out of Esselen Street Clinic, an old Hillbrow facility, home to the first South African HIV testing site, and from where he ran a huge US-government funded HIV support programme for the next decade across several provinces, gaining experience in expanding primary care approaches in chronic diseases.

Sponsored by

They were heady times, in which Venter was left disappointed again and again by much of the medical community.

“Other than the rural doctors, who have always fought for their patients, and the HIV Clinicians Society, the healthcare worker organisations were nowhere to be seen. The lawyers were there, civil society and the journalists, too, all fighting tooth and nail for access to therapy, but the professional organisations were too busy fighting for the interests of the profession,” says Venter, lamenting that little has changed.

“Through Covid-19, and now with the defunding of HIV and scientific research, it is the same people raising their voices, and the same organisations sitting on their hands. Worryingly, a lot of the people we are fighting are the same ones who stood in the way of access during the Mbeki era.”

Since those heady Esselen days, many important clinical trials, HIV programmes, research papers and court cases have gone under the bridge and Venter has become part of the moral conscience of South Africa.

Ezintsha, for years based in a Yeoville house, and Hillbrow back rooms, around which sewage spills split and foamed, now occupies two floors of a large office block in Parktown, an environment of biometric access controls and curvilinear glass, employing 150 people. On the upper floor is the Sleep Clinic, where patients with suspected sleep disorders lie back on R50 000 mattresses sponsored by a mattress company.

QUID PRO QUO: The Sleep Clinic at Ezintsha in Parktown treats people with suspected sleep disorders, with beds sponsored by a mattress company. It’s also now the home of a new obesity clinic with new drugs which, says Venter, are ‘every bit as fiddly as antiretrovirals were in 2000’. (Delywn Verasamy)

QUID PRO QUO: The Sleep Clinic at Ezintsha in Parktown treats people with suspected sleep disorders, with beds sponsored by a mattress company. It’s also now the home of a new obesity clinic with new drugs which, says Venter, are ‘every bit as fiddly as antiretrovirals were in 2000’. (Delywn Verasamy)

“The quid pro quo is that they be allowed to advertise,” says a faintly apologetic Venter, as we cross through an incongruous six-bed showroom. The Sleep Clinic also houses a new obesity clinic, where Venter sees patients with South Africa’s new pandemic. “The new drugs for obesity are every bit as revolutionary as the HIV drugs,” he says, “but every bit as fiddly as antiretrovirals were in 2000.”

New studies, using these wonder drugs in people with both HIV and obesity, are being hatched here. Ezintsha’s health staff are looking at using HIV lessons to try to improve primary care for diabetes, hypertension and other common diseases in South Africa.

The race to the bottom

We are a long way from Phalaborwa, a long way from the house in Yeoville, too, and while it is probably unfair to include Ezintsha in this observation, the transit away from the streets into cushy offices is one that many organisations working on HIV have made in recent years.

“It is nice not to have to worry about staff being pistol-whipped while at work,” remarks Venter, but he doesn’t dodge the inference, which is that donor funding, while key to the fight against HIV in South Africa, has also distanced organisations from communities, and created a dependency which, following the collapse of the US government’s Aids Fund, Pepfar, and the US International Agency for International Development, USAid, threatens catastrophe.

“What happened still feels quite unthinkable. On the one hand, it feels like 2004, when Mbeki’s denial of HIV became national policy and everything felt like it was going backwards. On the other hand, it is extremely frustrating that our systems have not been made sustainable and are now on the brink of collapse as a result of Pepfar having been interwoven with the national HIV programme to such an extent everything unravels when it is stopped.”

Venter sketches a scenario, in which South Africa’s HIV response — “the one effective programme we have” — is misleadingly characterised as “too expensive”, and dragged down to the lowest common denominator, “leading to the same terrible outcomes you find in crap programmes, like diabetes”. Patients in neighbouring countries such asLesotho, where the country’s HIV programme relied almost entirely on US funding, start crossing into South Africa en masse in search of treatment, where they are conveniently scapegoated by South African authorities for collapsing the health system.

MR FIX IT: Venter says getting ‘everyone from the president and the minister of health down’ to use the public healthcare system when using their medical aid will mean ‘they will have an immediate investment in assisting those fixing it’.

MR FIX IT: Venter says getting ‘everyone from the president and the minister of health down’ to use the public healthcare system when using their medical aid will mean ‘they will have an immediate investment in assisting those fixing it’.

“A race to the bottom, in other words,” says Venter. “We have poor indicators for almost every health metric outside of HIV, TB and vaccines, and even those are now slipping, due to the health department dropping the ball. Both our public and private health services are an expensive mess, for very different reasons. The health minister has been in charge for most of the last 17 years, we have endless excellent white papers and policy documents that gather dust, and little to show for the continent’s most expensive health system.”

Will this grim scenario prevail, or will South African healthcare be shepherded through the labyrinth of budget cuts and misfiring systems? Venter doesn’t see why not.

“It wasn’t so long ago that we seemed to be in the grip of load-shedding without end, yet Eskom was turned around in 18 months. Our problems are systemic and we have enough resources and brains to fix them. What is needed is strong leadership, which is something we currently lack,” says Venter, pausing to mull the judiciousness of his next point. It isn’t a long pause.

“I’ll tell you what you do. You take the top people from the medical aids and tell them: ‘You can’t be head of Discovery or the Government Employee Medical Scheme, Gems, anymore, lead with the best people from academia, from government, the private sector, donors, civil society, form a focused group with teeth, and run the health system.’

“We all declare our interests, put an end to corruption, and everyone from the president and the minister of health down in government must use the public healthcare system when using their medical aid. If they experience the system first hand, they will have an immediate investment in assisting those fixing it. Stop blaming the private sector and a lack of money for the problem.

“Start using the innovations South Africans are world leaders in, including data systems. If we do that, I am telling you, we will fix the system in five years.”

Venter, clearly, has already rolled up his sleeves for this new fight. It will be interesting to see who joins him.

This story was produced by the Bhekisisa Centre for Health Journalism. Sign up for the newsletter.